by Jon Brownlee, Combined Honours in Humanities and English 2016

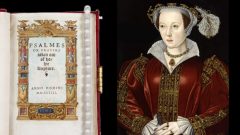

Professor Micheline White of Carleton’s English Department and the College of the Humanities was working on a research project when she made an important discovery about Katherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII. Professor White was researching Elizabeth Tyrwhit, one of Katherine Parr’s ladies-in-waiting, when she allowed herself to be diverted from her original path of research and began to investigate Katherine Parr’s first book, a book of prayers translated from Latin entitled Psalms or Prayers (1544).

Professor Micheline White of Carleton’s English Department and the College of the Humanities was working on a research project when she made an important discovery about Katherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII. Professor White was researching Elizabeth Tyrwhit, one of Katherine Parr’s ladies-in-waiting, when she allowed herself to be diverted from her original path of research and began to investigate Katherine Parr’s first book, a book of prayers translated from Latin entitled Psalms or Prayers (1544).

“Most people who have worked on this book talk about it as a literary and apolitical collection of prayers compiled from rearranged bits of the Psalms,” she explains. “But as I read it, I realised that it was a book of military propaganda designed to aid Henry VIII in his wars against the Scottish and the French.” Most of the prayers in Parr’s book are culled from Psalms that are about war and they ask for God’s help to vanquish England’s enemies.

Parr’s book ends with a prayer for Henry and this immediately struck White’s eye. “Depictions of Henry were carefully managed by his male advisors so I was surprised that Henry asked Parr to translate this prayer for him before he went to war,” she explains. Upon further research on prayers for monarchs, White discovered that this prayer was the first long prayer for the monarch ever published in England with royal sponsorship. She also noted that Parr made fascinating modifications as she translated the prayer, enhancing Henry’s masculinity and military prowess. Parr’s prayer for Henry was reprinted the next year at the back of her second book.

Given these interesting discoveries, White decided to pursue Parr’s Psalm book further, and went to see some of its privately owned first editions. These are gift copies that Henry and Parr had specially made and they were painstakingly hand-painted. “Just seeing these gorgeous books made me realize how important this project had been to Henry and Parr, and that’s when I became convinced that this prayer must have had an afterlife.”

The hunt for the book’s afterlife quickly yielded impressive results. White checked through some editions of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), the official Anglican Prayer Book first printed in 1549, for hints of Parr’s influence. To her astonishment, she discovered that Parr’s prayer appears in the Litany in the 1559 edition of the BCP, in a version that is shortened but otherwise identical. The prayer continued to appear in all subsequent editions of the BCP and in the translations of the BCP into more than two hundred different languages.

The claim that a woman’s writing could feature in the BCP is a radical idea that has never been seriously entertained. Traditional scholarship has attributed the BCP’s contents to Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1549, and to other high-ranking clergymen. White’s excavation of the prayer’s important afterlife led her to do research into the prayer’s origins. She finally discovered the source in a book at the British Library: a Latin prayer from 1541 for the Holy Roman Emperor and Henry’s military ally by the German priest George Witzel. Witzel had come into contact with English diplomats at the Diet of Speyer of 1544, and so it is easy to imagine how his book came to Henry and Katherine’s attention. “Apparently Katherine and Henry saw the prayer for the Emperor and decided that it would be a good idea to adapt it as Prayer for Henry.” Parr’s second book contains some unattributed prayers and White realised that one of them was also adapted from Witzel. So it is possible that Parr was involved in adapting Witzel’s prayer for Henry before she translated it into English.

The claim that a woman’s writing could feature in the BCP is a radical idea that has never been seriously entertained. Traditional scholarship has attributed the BCP’s contents to Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1549, and to other high-ranking clergymen. White’s excavation of the prayer’s important afterlife led her to do research into the prayer’s origins. She finally discovered the source in a book at the British Library: a Latin prayer from 1541 for the Holy Roman Emperor and Henry’s military ally by the German priest George Witzel. Witzel had come into contact with English diplomats at the Diet of Speyer of 1544, and so it is easy to imagine how his book came to Henry and Katherine’s attention. “Apparently Katherine and Henry saw the prayer for the Emperor and decided that it would be a good idea to adapt it as Prayer for Henry.” Parr’s second book contains some unattributed prayers and White realised that one of them was also adapted from Witzel. So it is possible that Parr was involved in adapting Witzel’s prayer for Henry before she translated it into English.

That Parr was so closely involved in the circulation of this important state prayer surprised White, but the way that the prayer found its way into the BCP turned out to be equally unexpected. The prayer first appeared in the BCP in June 1559, roughly six months after Queen Elizabeth I came to power. This was a time of religious upheaval in England, as the preceding Queen Mary had reinstated Catholicism, and rulers across Europe were waiting to see whether Elizabeth would reintroduce a new Protestant BCP or not. Unfortunately there is no documentation about who was responsible for making additions to the 1559 BCP. However, it has long been known that the Litany was the one part of the BCP that was not illegal under Mary and was used as soon as Elizabeth came to power in November 1558. This turned out to yield a crucial clue for White, who was able to uncover a rare copy of the Litany from Elizabeth’s Chapel Royal during this interim period and found that Parr’s prayer was included. This detail strongly suggests that Elizabeth was responsible for introducing Parr’s prayer into the BCP. “Elizabeth is assumed to be responsible for any new or unusual things that took place in her Chapel because the Dean of the Chapel reported directly to her.” Elizabeth had had a strong emotional attachment to Parr as a teenager, and had once translated Parr’s prayers as a gift for Henry. It thus made sense for Elizabeth to turn to Parr’s prayer as a way of asking her subjects to pray for her as she assumed the throne.

Given that the BCP has been in heavy circulation and is still widely used in the Anglican Church after nearly 500 years, White was amazed that the details surrounding Parr’s and Elizabeth’s contributions to it had not been discovered earlier. During the course of her research, White found that earlier historians had, in fact, noticed a connection between the 1559 “Prayer for the Queen” and the earlier “Prayer for the King.” However, these historians were unaware that Parr was the translator of the 1544 Psalm Book and that the prayer originated in Germany. They assumed that the prayer for Henry was produced by some unknown person and was simply appended to the back of Parr’s second book in 1545. “These historians do not entertain the possibility that Parr was involved in the production of this prayer. As time goes on, Parr’s name gets erased, so that in the recent Oxford edition of the BCP, the editor just says that the prayer first appeared in ‘books of private prayers in 1545 and 1547.’ Parr is not mentioned by name.”

White attributes this gradual erasure of Parr’s contribution to the BCP partly to the deep-seated assumptions that a patriarchal account of history can engender, even among fastidious historians. White’s tracing of the history of the prayer from Germany to the BCP has sparked an interest beyond the academic sphere, and she has had opportunities to present her findings to the public. After publishing her research in the prestigious Times Literary Supplement in April 2015, White gave a series of interviews about her research to the CBC, Radio-Canada (a French language interview), and the Anglican Communion News Service. She says that the public’s reception of her research gave her the kind of fulfilment that academia rarely offers. “I’ve received emails from Anglicans all over the world who have heard this prayer in their churches, but never knew about its history. Several Anglican priests have used this research in their sermons and so Parr’s and Elizabeth’s contributions to the Anglican church are becoming more well-known. When the Anglican Communion News Service ran a story on it, a thousand people were talking about it on Facebook. As a scholar, I’m used to talking to other scholars, but it was so rewarding for me to see that people outside the academy care about this.”

Much of the public interest in White’s research has been focused on the questions of gender bias in academia. Had White skimmed through Parr’s writings assuming that they were no more than “private prayer-books,” Parr’s prayer could have spent more decades in obscurity. White is confident that researchers will continue to uncover the ways that women have shaped history both during the Reformation and elsewhere.