By: Allison Norris

In their presentation at the Food Matters & Materialities: Critical Understandings of Food Cultures conference, Katie Konstantopoulos, and Koby Song-Nichols shared their research, which positions Peking and Cantonese roast duck as delicious meals but also as materials sites of cultural meaning. The presentation “It’s in the Duck: Diaspora and Thinking Dialectically in a Settler Colonial Food System” traces the Pekin breed of duck’s place in agriculture, the space it occupies on the table, and even through our own consumption. Farmed at just three locations across Canada and only one location in Ontario, Pekin duck offers an opportunity to think about colonialism, diaspora, food systems, kin, and even imagine new futures of collective action and mutual aid. Konstantopoulos, an independent researcher who also works in sustainable planning, and Koby Song-Nichols, a Ph.D. student in history and food studies at the University of Toronto, examine the lessons we can learn from farming, advertising, cooking, and eating duck. I had a chance to catch up with them after the Foods Matters conference to discuss their research. The following conversation focuses on their work as it pertains to the intersections of the relationships between diaspora, traditional foods, settler-colonial responsibility on Indigenous lands, and how we can all move forward, eating and thinking dialectically.

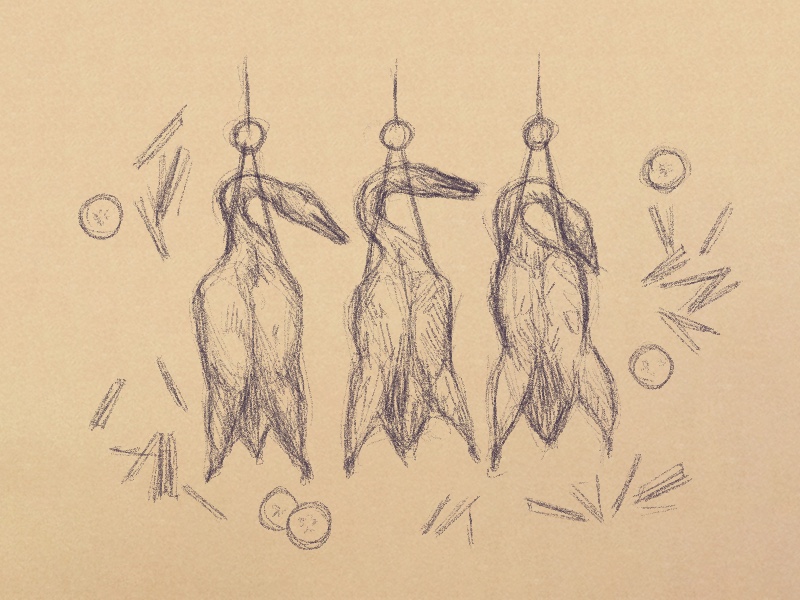

Credits: Illustration by Kit Chokly.

Allison Norris: What drew you to diasporic food history and communities? And what drew the two of you to work together?

Katie Konstantopoulos: Initially, the idea was to expand into and learn about diasporic foodways from perspectives other than my own. My background is in Food Studies and diasporic history of Greek, Macedonian, and Balkan communities, specifically in diasporic kitchens. This project came out of an undergrad project I was given when I was studying at University of Toronto, Scarborough – I was asked to learn about duck. This project has a lot to do with the Chinese community, and that was one reason Koby, and I began collaborating. For me, there was a desire to understand my own diasporic history, my family’s immigrant history, and place that within the Canadian context. I was also learning about the history of treaty land and trying to place myself within the context of Indigenous history as well.

Koby Song-Nichols: When Katie first brought this project to me, I was just beginning Food Studies. My previous interests were Asian-American and Chinese-American Studies. When this duck project came about, I had the initial response I think many people have to our research: Duck? Really? Why? But it has been a fascinating way to think about different diasporic connections I have close to my heart. The ways diasporic people relate to settler colonialism are not as straightforward or transparent as other identities.

I was drawn to this project and drawn to research duck based on my family history as a Chinese-American. I have a distinct memory of a family gathering. We had a massive roast Cantonese duck on the table. I was young and sitting next to my great uncle. He kept piling duck on my plate, and I would eat it because I wanted to be polite. I had pretty much eaten the entire roast duck. My uncle said, you’re growing, keep going – I was sick afterward! But this feeling of care and familial connection brought me to this project, to learn or unpack all the meaning behind it.

AN: I love that notion of care or over-care. And that somewhat answers my second question: Why ducks? Why ducks of all the farmed animals in Canada which make it onto our plates?

KK: Kobe and I have talked about this many times. Duck is niche and unique. You can trace duck on a local level and talk about so many different things. Duck is such an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary space to talk about human and non-human and kin studies, but you can have scientific conversations as well. Bringing duck into diaspora and focusing on human interaction [with it] is where we can interrogate our own biases.

KSN: Duck is, in some ways, an obvious choice from a Chinese-Canadian or Chinese-American Studies perspective because the Peking Roast Duck is super prominent in Chinese diasporic cuisines. For many people, Chinese and non-Chinese, the imagery of roast ducks hanging in the window is iconic to Chinatown. Coupled with the origins of these ducks—the one family farm in Ontario that has its own production and promotional imagery of duck—how do we reconcile these two images? What images do we have access to when interacting with both of these duck images, based on our own positionality, interest, and palettes? Duck opens up all of these conversations and research avenues.

KK: We trace our own migration, but do we trace the migration of our food alongside us? We’re trying to tease out the concept of duck as a migrant to Treaty 13, duck as a treaty entity, and what that means for non-human kin. How can we come into relation and understand our food system, not just in a very industrial, capitalistic, and colonial sense, but also learn from our Indigenous kin and the knowledges that have been shared, in order to understand we all have a place and a part to play in the food system. We have to understand how everything that we’ve interacted with, everything that we’ve brought along with us, impacts the food system and Indigenous peoples as well.

KSN: Diaspora has its origins in historical moments where a group has been forced to move away from a homeland and are dispersed large lot across long distances. What does that old homeland mean to you? For immigrants or migrants, that adds to nostalgia or missing home, as a deep interrogation of what home is, or can mean, and all the related conversations. For me to identify as part of a diaspora is to open my heart and mind to different ways of coming into relation to the various places I’ve found myself. It’s a way of recognizing my connection to Chinese culture to various historical Chinese homelands and also to the United States, now that I’m outside that country.

KK: What also ties that together is the ‘imagined community’—an idea from Benedict Anderson and other folks who have taken up this work—the idea that we are all tied by the way that we imagine our homelands, our homes, our communities, and our relations to one another. I see diaspora as a consistent sense of placelessness, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s understanding the way that migration consistently moves us, how we relate to our places, and the spaces that we call home, or the spaces that we are coming to as guests. I’m a white person, and it doesn’t matter how I claim my history – Greek or Macedonian – my settler-colonial ancestry goes much farther back than just being here in Canada.

AN: Your work is done with an orientation toward, as you say, “more ethical engagements with our Indigenous hosts”? Your presentation mentioned a number of non-Indigenous groups, like settler-descendants and diaspora. How are these distinctions important to your research?

KSN: This is part of ongoing debates within academia and various fields. For us and our research, it’s not about teasing out the differences between those categories. We’re finding ways that we can all relate to the colonial-settler system that we’re in, the roles our ancestors have played in these systems, the roles that we can play, and reflect on what we are participating in. We’re asking diaspora studies to continue to ask questions about how we are implicated in various structures and how can we work towards more solidarity or reimagining futures which don’t have the same oppressions or marginalizations that we currently have.

KK: We use diaspora as a way to understand the unsettling that is asked of us – decolonization is meant to unsettle us. What does diaspora bring to us? It brings to us a sense of non-belonging and belonging – this is where our paper specifically originated. What can it mean when a diaspora resists being complicit in the settler-colonial state?

AN: What is the relationship between food and decolonization?

KK: Our food systems are complicated by violences, the migration of other foods here, but also the decimation of food systems long cared for by the Indigenous peoples of this land. Does duck have that flavor? Can you taste it? Can you taste colonialism? Can you taste white supremacy? Does it make you uncomfortable? If you’re interrogating that, being critical, have a critical food consciousness, and are eating dialectically, you will be able to understand how these histories are embodied in foods and how you’re implicated by consuming them.

AN: What does it mean to eat dialectically in our everyday lives? What can people engage with daily, as informed by your research?

KSN: The notion of eating dialectically emerged from Grace Lee Boggs’ notion of thinking dialectically—the process of continually challenging yourself to reimagine yourself and how you relate to everything else. Recognize the ways that our imagination has been shaped or limited based on the realities that we see and things we interact with.

So when I eat Cantonese food, I immediately think of that memory of my uncle caring for me. I can also think about the ways that connect me to Chinese communities here and the different foodways. If I keep going, I see how duck connects me to a rural Ontario farm and histories of settler colonialism. What does Cantonese roast duck in Toronto look like if I more critically engage with food system? How will I have to change? How will my diet have to change? What work will I have to do in this food system to make this duck sit right with my new knowledge of the food system?

It’s a constant evaluation. Our work moves beyond a critical consciousness of food toward a greater sense of freedom or a reimagined future where everyone is better nourished, well-nourished, more sustainably and regeneratively, a future better for everyone.

AN: Your presentation also talked about cultivating relationships, taking responsibility for your actions, a commitment to practice of settler harm reduction. What does this look like? What steps would you encourage people to take?

KK: We are not experts—our positionality holds that we don’t know. Do the research, find out what land you’re on, whose land you’re on. Many Indigenous communities are speaking up and asking us to show up. In some cases, this might also look like paying reparations, donation. Work within your community to figure out your next steps. You might not know them yet, but your space will become known to you. We work in this academic forum because that’s where we are right now. Wherever you are, you’ll find an avenue for this kind of work.

KSN: We are still beginning to walk the walk that we’re talking. Part of what this theoretical model hopes to work toward is the openness of heart and openness of mind needed to make sure that people are in a good place to open these dialogues, to reimagine oneself. What are my own dreams and my own futures? How can I challenge those when I listen to activists, people who work hard to make a difference and help the most vulnerable in our society? When in a crisis, [and] we find ourselves in many crises right now, there are folks trying to make it easier and create the opportunity to help each other. By eating dialectically, we can look for those opportunities, open our hearts, and be able to better help each other, which leads to systemic changes.

Thank you to Katie Konstantopoulos and Koby Song-Nichols for taking the time to speak with me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you’re interested in hearing more about the relationship between decolonialism and food systems, check the podcast about Taylor Wilson’s research on the Canadian Food Guide, available as part of the Food Matters outreach materials.