By: Arlette Martinez

Ran Xiang is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at UBC, focusing on Art Education. During her presentation ”The Magic Leaf: Tea and Materiality” at the Food Matters and Materialities Conference, Xiang explained that tea is a complex object: its taste is affected first by the environment where it grows, second by how it’s harvested and dried, and finally by how it’s served. Moreover, many people are involved in tea production, which means tea is a factor in various social relationships. Xiang’s research explores the concept of materiality through “Yan Cha” or “Cliff/Rock Tea” and the webs of relations connected to this peculiar tea’s production, distribution, and consumption.

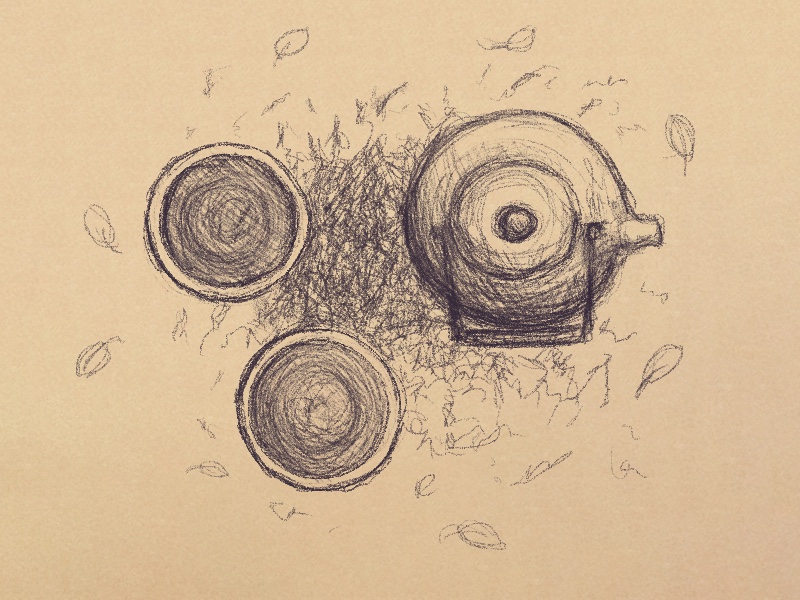

Credits: Illustration by Kit Chokly.

Rock tea is a type of oolong tea produced in China’s Wuyi Mountains, where the soil is rich in minerals, and the moisture is high thanks to the surrounding rivers and bamboo forests. The name comes from the fact that the tea inherits a distinctive mineral, roasted taste, thanks to the soil, or terroir, much like a wine would. Rock tea is usually darker and oxidized. Compared to other types of Oolong tea, Rock tea is twisted into strips instead of rolled.

Tea’s making and aging processes affect its taste and therefore speak of its quality. This lengthy process involves human and non-human “actors” (environmental factors, place, techniques, etc.). Xiang explores how tea’s taste affects people’s emotional and affective states and gives various meanings to tea. She has attended a few tea ceremonies and is keen on learning more about the practice. There are tea experts who, much like sommeliers, can taste all the nuances of tea and assess its quality. Some tea connoisseurs and enthusiasts develop their tea vocabulary using what they learned from professionals through tea ceremonies and other related events. Xiang points out that this rise in popularity and demand for rock tea (and other rare teas) has given way to tea collections by connoisseurs and forgery by some tea merchants.

Although there are hundreds of types of tea, Xiang chose to focus on rock tea because of its complexity. Through her research, Xiang will also try to learn the differences between a Chinese tea ceremony and a Japanese ceremony, something she looks forward to.

“Personally, rock tea is the most interesting because it grows in a particular region in China, and its making process is arguably the most complicated out of the six species of tea. In terms of the taste, to me, it’s the most varied and exuberant.”

During her presentation, Xiang also pointed out the importance of the interaction between the tea leaves and their environment and the machines used to process them. Tea’s final flavour also depends on the skills of those who produce it. For these reasons, tea has become a luxury product, and its price can increase exponentially. According to Xiang, a market has opened for counterfeits and lesser quality products purposely mislabeled as of higher quality.

Physically, tea’s taste changes over time. In 2014, Xiang added aged white tea to her collection, but it was produced in 2010. By the time of our interview in 2021, the tea’s taste and colour were quite different from when it was newly picked and rolled. Tea’s interaction with its environment drives Xiang’s curiosity. Drinking tea also helps her unwind and engage with all her senses:

“Whenever I feel under the weather, I drink strong tea, and it will make me feel a lot better. It creates a sort of moment in the day where I feel peaceful. Tea also has a long history in Zen Buddhism. It has a sort of spirituality within it.”

Tea is a simple drink to most people. Still, to some connoisseurs, it’s a complex cultural object with discernible taste profiles, and teahouses are unique spaces dedicated to bringing people together to sample specialty teas. These places are common across Asia, but there are also some in Canada, especially in Vancouver. Tea houses have a specific layout, lighting, and music to make the experience more poignant. Drinking tea at a teahouse or participating in a tea ceremony are moments that separate it from everyday life.

Xiang explained that, in her view, tea is both soothing and energizing: “I think it’s quite a charming emotion attached to it. “[Tea] satisfies my curiosity and gives me a lot of joy. But when I drink it, I’m also very concentrated and ‘in the moment.’ I want to continue to do fieldwork and interview people. I want to know if that’s what they felt too.”

There is so much to unpack through a little leaf, and research can sometimes be a seemingly endless and lonely endeavour. When I asked Xiang what motivated her to take on this project and how she keeps motivated, she said the key is to have a genuine appreciation for the object of study, but finding joy and taking care of oneself is also important: “It’s a personal interest turned into a scholarly pursuit. I find it fascinating, and it’s also an everyday thing for me. In the morning, I use a big mug and pour hot water on the tea leaves because it makes the smell come out immediately. That kind of sets me in a good tone for the day ahead. I would say it’s an everyday drink, and yet it’s very joyful for me”.

Not surprisingly, there is a lot of history behind tea, and I can understand why it is a fascinating object of study. I hope this conversation inspires you to be curious about what’s behind your next cup of tea!