![]()

By Karen Kelly

Joanne MacIsaac had never interacted with the police until the day her brother Michael was killed while in police custody in 2013.

“His wife called because he was having seizures and he had run from his house naked,” says MacIsaac of her brother, who suffered from epilepsy and was in crisis. “I called the police and then I didn’t hear anything until his wife called back. She was screaming that they shot him.”

The Durham Regional Police never told MacIsaac and her family that her brother had been shot. That was the beginning of her work as an activist.

“I was never involved in any type of activism prior to this. But I think that was how I coped with the grief,” says MacIsaac. “We spent thousands of dollars and hired independent investigators and nothing we found matched the police scenario.”

After sharing her story publicly, MacIsaac began receiving phone calls from other families whose own family members had been killed. She started a database of police-involved deaths, which was one of the inspirations for the Tracking (In)Justice: A Law Enforcement and Data Transparency Project, led by Professor Alexander McClelland in Carleton’s Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice. MacIsaac is on a council of family members who will soon guide the project.

“Building off past initiatives, we collaboratively created this database because there is no official oversight body that collects information on the number of people who were killed by police or different law enforcement agencies across Canada each year,” explains McClelland, who received a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) grant. “This is just basic information that criminologists should know and the Canadian public should know.”

The searchable database demonstrates that the number of people who have been killed in Canada in a police interaction where force was used has risen over the past 20 years. At least 704 people have been killed or died during police use of force encounters in Canada since 2000. Sixty-nine were killed in 2022. Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately representative and the data shows that 72% of these deaths were caused by guns.

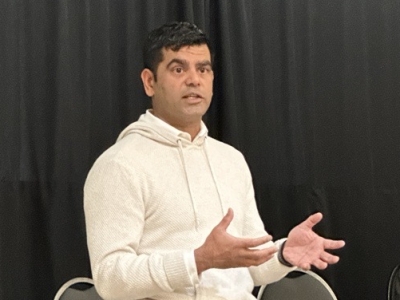

Prof. Alexander McClelland

McClelland says it’s not easy to find this data, nor verify it at times.

“We have discussions on our website about the complexities of relying on data sources like [those from the police]. We are really working in a trauma-informed way.”

Other partners on the project include the Centre for Research Innovation on Black Survivors of Homicide (CRIBS) at the University of Toronto, the Queen’s University computer science department, aboriginal legal services, Trans Justice, and more.

“I think the police services themselves should want to look at this data. You should always be trying to improve,” says MacIsaac, who has launched a petition that calls for a official database of deaths or injuries caused by police. She is also active on Twitter.

While the project is launching with data on deaths at the hands of police, it will expand to deaths that occurred during all police interactions in the future. McClelland says the project reflects the changing focus of criminology.

“This is connected to public criminology that is interested in intervening in social issues and providing an evidence base to help inform social movements that are calling for social transformation and forms of justice that are conceived of outside of the criminal justice system themselves,” says McClelland. “This will hopefully help some communities with their calls for advocacy, calls for change, and calls for justice.”

Thursday, February 23, 2023 in Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice, News

Share: Twitter, Facebook