Walter

Walking the Via Egnatia with Walter

by Walter Wilmot, with pictures by Walter.

Last year I was continuously inspired as I attended Marianne Goodfellow’s course “Issues in Classics: Travel and Sightseeing in the Ancient World.” Our text was rich and worthy, Travel in the Ancient World by Lionel Casson. Some of the early content that fascinated me was a mention of the ancient ‘rut roads’ to Greek sanctuaries and the trail of mythological repute from Corinth to Megara above the Scironic Rocks that can still be seen today.Then one day she mentioned the Via Egnatia. It is a Roman road, about 1000 kilometers in length, six meters in width and “paved” with stones, that stretched from the Adriatic coast of what is now Albania across the Balkans, past Lake Ohrid, Heraclea Lyncestis, Pella, Thessalonica, Amphipolis, and Philippi, all the way to Constantinople.

The Roman Via re-surfaced and upgraded by the Italian military in 1940 after their invasion of Albania using the timeless technology of the then impoverished southern Europe

On my “bucket list” has always been the desire to visit southern Europe and so Marianne’s mere mention of this Roman road led me to fantasize about tramping along its stone surface – if parts of it could be found. I read that the road was built in the second century BC as the continuation of the Via Appia, and that it has a long history and purpose that continues to this day. Its importance for military forces, economies, and communication is well documented in the book The Egnatian Way by Firmin O’Sullivan (1972). Madam Google led me to the Via Egnatia Foundation which has published a guide book for travelers today to follow the route. I realized that there was no going back. With my experience of having twice walked the “El Camino,” that Medieval pilgrimage route across northern Spain, and a tablet in my backpack with both a good translation app and mapping app, I left Ottawa in late March 2017.

I began my walk in Durrës or Dyrrachium, as it was known in ancient Illyria, a terminus of the Via Egnatia on the Albanian coast, the other being Apollonia a little further south. Albania is very poor; unemployment, organized crime and corruption are high, and there is no trust in the politicians. Locals described their country to me as “broken,” comparable to North Korea, as a vast prison with most young people wanting to emigrate or at least get a legal work permit for somewhere, anywhere. I do not think, however, that you would find a more hospitable people. I believe it related to their cultural sense of honour. Just ask for directions along the road and you will be offered a glass of homemade raki, a meal, and even a sleepover! (I was given a free meal in a restaurant, a collective taxi ride, and small items in a corner store as presents.) Albania is extremely safe for travellers and it has the least tourist infrastructure of any European country. That is a good thing. You can visit the sites such as Apollonia or the World Heritage site at Butrint tourist-free; when the daily tour bus leaves…silence, peace and presence, hours of it, unlike sites in Greece where I ended my journey four months later.

The legacy of the Roman road continues in Albania today with the Rruga Autostrada Egnatia, reconstruction of which has exposed Roman Durrës near the Venetian Tower. (While I was there French archaeologists found a human skeleton just beneath the tarmac.) I found the city’s archaeological museum very Zen, very Roman. From Durrës on my first day along the Roman road itself, I walked as far as Pequin (pronounced Peh-cheen) and I saw ten to twelve donkeys. My first sighting was a donkey saddled with a large load and accompanied by a man who was talking on his cell phone. Later on I took a rest by the roadside and heard two peasant women chatting. As I looked over, I realized it was one woman talking on her cell phone. Globalization!

An Albanian and his donkey on the Roman road

Before I continued eastwards from Pequin toward Lake Ohrid, my goal for this stage of my pilgrimage, I made a detour and stopped in Apollonia, a Greek colony founded in 588 BC, once home to about 60,000 people but abandoned in the Middle Ages. It took me a few hours to find the ancient acropolis since there was no signage. I found out that it had been ruthlessly tunneled and bunkered when, under communist dictator Enver Hoxha, the country was mobilized for a defensive war. Pillboxes and bunkers, a minimum of 200,000 of them, were built all over the country including the Apollonian acropolis and in strategic places along the route of the Via Egnatia.

Some of Hoxha’s bunkers where sheep graze along the road

The nymphaeum just below the acropolis at Apollonia was discovered during construction of the bunkers and excavation followed. But again, I had trouble finding the site due to the absence of signs. The ruins made me realize that the nymphaeum, sacred to Pan and described by Strabo, must have once been magnificent to see. Today the ubiquitous Albanian sheep graze happily among the ruins. I walked around a Roman-era street corner in the Apollonian agora, only 5% excavated to date, with its shops, the bouleuterion, and theatre. I also saw the Apollo Agyieus obelisk; as patron of public places, streets, houses, and colonists, he was worshipped in this form and not in a temple.

The Roman Nymphaeum at Apollonia

Over the next few weeks I continued along the way to places like Elbasan, identified with Mansio Scampa, a Roman “stopping place” along the road, and Ad Quintum (at Five Miles), a mutatio or “changing place”. Few mutationes and mansiones have been identified archaeologically though they are listed in the Roman imperial Antonine Itinerary, as well as the Bordeaux Itinerary written by a Christian pilgrim in 333 AD. The remains of Ad Quintum, which include a Roman bath, were discovered accidentally when exposed after a landslide in 1968. On the steep slopes along the Shkumbin River (ancient Genusus), which the road follows for some distance, these landslides are common and must have made road maintenance a labour intensive challenge for the Romans – and for the Byzantine and Ottoman administrations that followed.

The Via Egnatia along the steep slopes high above the Shkumbin River with two bunkers just visible

I reached my destination of Lin with its 5thcentury AD basilica above Lake Ohrid after four weeks on the road. I took my time. I watched the locals walk to their fields every day at 7:30 am and return late afternoon. Not a machine or motor to be heard. I loved it. I rested here a while and reflected on my journey which at times was physically demanding and very difficult but two aspects of it made it quite special. One was the landscape itself, wild in places with rugged mountains and the river below. In some villages there were no cars, just the sound of roosters, the odd cow, and birds. I came across a number of Moslem cemeteries in some beautiful spots along the road, the burials facing northeast looking towards Mecca.

A Moslem cemetery along the Via Egnatia

The second aspect of my journey that made it memorable was the kindness of strangers. I never met a more hospitable people. They fed me cheese, lamb, bread and butter, veggies, from their sweat and toil. They gave me a bed for the night and 500 ml of their homemade raki for the road. I learned of the hard life of these people; one young man I met, a heavy equipment mechanic, earns $1.00 per hour, 6 days per week, no sick leave or vacation pay. He feels fortunate to even have found work. He learned English by working illegally in Greece, as most Albanian males have done. Immigration authorities discovered and deported him.

The kindness of strangers

I left the Via Egnatia at Lake Ohrid (with Albania to the west and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) to the east), and I headed east to the hot spring resort of Sandanski, Roman Parthicopolis, in Bulgaria where I spent three weeks on an archaeological excavation with the summer program of the American Research Center in Sofia (ARCS) Foundation at the site of a 6thcentury basilica. The final leg of my pilgrimage was a three-week tour through Greece with the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. It was an honour to experience it through this gold standard of archaeological institutions. I finally returned to Ottawa more than four months later.

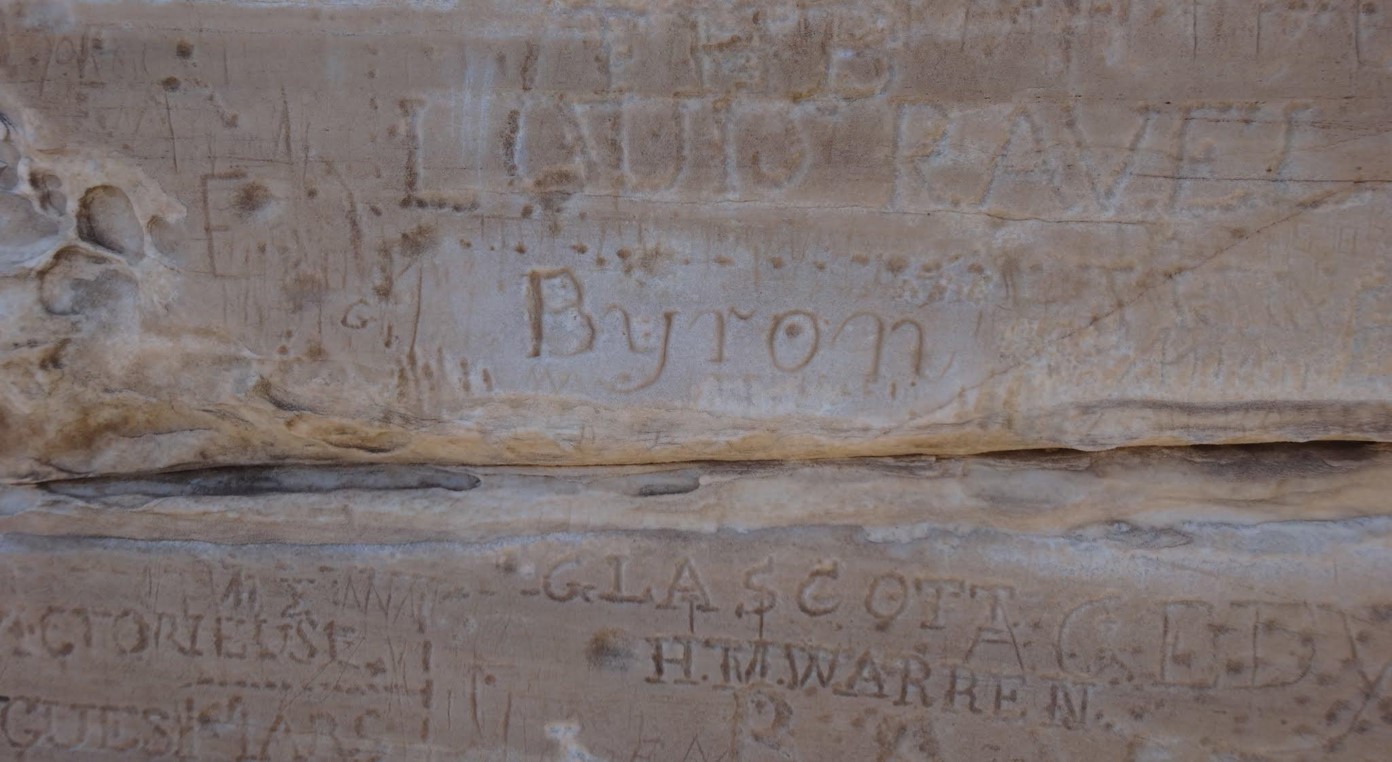

I never anticipated that passing mention of one Roman road in Marianne’s classroom in Paterson Hall could have ever had such consequences for me (nor, for that matter, did she). And it was not just that delightful road. One day early in the course, she had mentioned Sounion. So one of the last acts of my pilgrimage was to see Lord Byron’s signature where he carved it himself in 1810 on the marble of Poseidon’s temple. To quote from his poem:

Place me on Sunium’s marbled steep,

Where nothing, save the waves and I,

May hear our mutual murmurs sweep;

There, swan-like, let me sing and die:

— (Don Juan, Canto III “The Isles of Greece”, Section 86, stanza 16)

Lord Byron’s signature at Sounion