Table of Contents

- Welcome

- Travels to an Antique Land

- Susan and Servilia

- Joy’s Bookcase and Book Reviews

- Book Review

- Beer’s Blog

- Our Poet’s Corner

- A Final Word of Thanks

Welcome: Classical Companions in WW1

Marianne Goodfellow

Editor, FGRS Newsletter

Dear Friends,

In those months between the end of the winter term and the beginning of the fall term, I turn my attention to something that I have been working on for some time and it has nothing to do with the courses I teach or Vergil’s Georgics. I turn my attention to my great uncle’s diary for 1917, that year of terrible and famous battles at Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, and Passchendaele. To help me understand better Warren’s experiences in the war and specifically the Canadian Field Artillery, I have been reading personal memoirs of WW1. I keep track of many descriptions in these memories of the gunners and drivers, the horses and mules, the guns and gas. But I also keep track of references I come across to Classical authors and subject matter.

This summer I read GoodBye to All That, an Autobiography by Robert Graves, the famous British poet, novelist (I, Claudius, Claudius the God, and Count Belisarius), and translator of Greek and Roman authors. I was amused to read about his early schooling when he wrote: “I had started Latin, but nobody explained what ‘Latin’ meant; its declensions and conjugations were pure incantations to me.” But in growing up and becoming a soldier, he seems to have gotten beyond the mysteries of learning Latin for returning to France after a time in hospital convalescing, he packed in his bag “a Shakespeare and a Bible, a Catullus and a Lucretius in Latin.”

I also read Shrieks and Crashes. The Memoir of Wilfred B. Kerr, Canadian Field Artillery 1917. From Seaforth, Ontario, Kerr’s university education was put on hold when he enlisted but he later earned degrees at Oxford and the University of Toronto. He knew something of the classical world. In his vivid memoir he likens attitudes of the audiences of gladiatorial combats in the amphitheatres to the spectacles of the airplane battles in the sky. He recalls Herodotus’ account of Xerxes’ soldiers at Thermopylae, and elsewhere in telling of rumours about preparations for an attack, Kerr likens himself to the historian, “I affirm, with Herodotus, that it is my duty to report what I have heard, but not necessarily to believe it.” But it was his reminder of Homer that really made me pause for a while. Kerr describes the early morning sky over Vimy Ridge: “Finally, a trace of a lightening in the east, gradually changing to a faint glow while the stars and moon paled; streaks of colour which made me think of Homer’s rosy-fingered Dawn.”

Travels to an Antique Land

Professor Susan Downie

Susan Downie who teaches Greek language, history, and art and archaeology at Carleton travels as often as she can to the Mediterranean. This past spring she was again on the island of Crete to visit as many sites as she possibly could in a short period of time.

Crete 2018

If you ever get a chance to travel to Crete, go. For almost 30 years now, it has been my favourite part of Greece and every time I arrive on the island I remember why. Busy cosmopolitan cities and small hillside villages filled with warm and generous people, delicious food, majestic mountains, some of the most spectacular beaches on the planet and, of course, fascinating sites from every period of human history.

I spent just 11 days on Crete in June as research during my sabbatical, visiting sites that I teach about in many classes. Do I admit that it was a huge relief not to travel with a bus load of students and have to lecture at every site upon arrival? Just rent a car and drive up every tiny mountain road — not to mention several goat tracks — impassable for a tour bus, hop a few farm fences, walk for about half an hour and there you are.

Even traveling with a fellow aficionado of Minoan culture my original itinerary was overly ambitious: 50 sites in 9 days with a rental car. That did not take into account the logistics of hiking up to numerous, inaccessible high mountain sites – like the Late Bronze Age refuge town of Karphi “The Nail” in eastern Crete or the peak sanctuary of Vrysinas, high above the Mycenaean cemetery of Armeni and city of Rethymno. Nor did it include getting lost on Psiloritis, Crete’s highest mountain — well beyond the range of any GPS — when searching for the cave of Idaean Zeus.

Apparently, Google wants you to drive right over the peak instead of going around to find the cave. We made it in the end (by going around), but had to skip the Minoan city of Zominthos on the way down. In the end, we made it to 30 sites — over half of which I had never seen before — and met several scholars working on Crete, both at the Villa Ariadne in Knossos and in the Lasithi plateau. I came home with a renewed sense of awe at the resilience of humans to adapt and suit themselves to some of the most extreme and unusual landscapes.

My interests lie primarily in the Bronze Age and with the Minoans, but we also visited Archaic, Classical and Roman sites, Turkish and Venetian forts, and memorials to Nazi occupation in World War II. In recent years Crete has been the centre of major archaeological discoveries — stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic and fossilized human footprints 5.7 million years old — that may rewrite our understanding of the earliest hominid presence in Europe. So there are many reasons to go back.

Photo Gallery

Upcoming Trip to Greece in May 2019

- Itinerary (PDF)

- Costs and payment information (PDF)

Susan and Servilia

Professor Susan Treggiari

Susan Treggiari has written a book about Servilia, mother of Brutus — one of Caesar’s assassins — which is soon to be published. Some of you know Susan and will remember those years when she was a professor in the Classics Department of the University of Ottawa (1970-82). She moved on to Stanford University in 1982 and taught there until 2001 when she and Arnaldo then returned to Oxford.  She is Bass Professor Emeritus in the School of Humanities and Sciences (Dept. of Classics) at Stanford and a retired member of the Faculty of Classics at Oxford, and it is there that she has continued her research leading to this new book. It follows in the tradition, as it were, of her interest in and publications on Roman social history, family, and marriage.

She is Bass Professor Emeritus in the School of Humanities and Sciences (Dept. of Classics) at Stanford and a retired member of the Faculty of Classics at Oxford, and it is there that she has continued her research leading to this new book. It follows in the tradition, as it were, of her interest in and publications on Roman social history, family, and marriage.

Susan was my teacher and mentor, and has become a dear friend. I asked her a while ago if she would contribute something to the Newsletter for old time’s sake and she has done so by introducing us to this woman named Servilia whose place in Roman history has until now never been fully chronicled.

Read Professor Treggiari’s article Servilia Who?

Joy’s Book Case

This is a regular feature of the Newsletter, which includes at least one book review and additions to a list of books about Classical Antiquity, or somehow related to it, though not textbooks as such. The list is eclectic and I hope that readers will contribute to the list and/or write reviews of books that might be of interest. (This feature, as explained in last year’s Newsletter, is named for my friend, Joy Barrie, who was a student in the Classics Dept. some time ago and continues to give me books to read.)

This is a regular feature of the Newsletter, which includes at least one book review and additions to a list of books about Classical Antiquity, or somehow related to it, though not textbooks as such. The list is eclectic and I hope that readers will contribute to the list and/or write reviews of books that might be of interest. (This feature, as explained in last year’s Newsletter, is named for my friend, Joy Barrie, who was a student in the Classics Dept. some time ago and continues to give me books to read.)

Travellers To An Antique Land. The History and Literature of Travel to Greece by Robert Eisner (1993)

On the Spartacus Road. A Spectacular Journey Through Ancient Italy by Peter Stothard (2010). Mr. Stothard was editor of The Times and then the Times Literary Supplement.

Book Review: An Affair of the Heart

Author Dilys Powell

Pam Gahan has written a review of a book by Dilys Powell that was in the Book Case list last issue. I loved the book and asked Pam to write about it because she has read it four or five times and been to both Perachora and Mycenae.

An Affair of the Heart by Dilys Powell (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1957)

Book review by Pam Gahan

Each of us has no doubt had the experience of enjoying a book so much that we vowed to read it again. During an extended stay in Athens many years ago on the recommendation of a friend I read Dilys Powell’s An Affair of the Heart. Decades later I can say that I have re-read it with great pleasure many times.

In An Affair of the Heart (an elegant title for a beautifully written book) Powell writes a moving account (on many levels) of her experiences in Greece in the mid-20th century. Background: Dilys Powell and Humfry Payne met when they were students at Oxford in the early 1920’s. She was studying Modern Languages, he Classics and Archaeology. They married in 1926, and in 1929 Payne was appointed Director of the British School at Athens; Powell was by then a journalist with the Sunday Times, a position she held for over fifty years.

Humfry Payne

In the early twentieth century, archaeological fieldwork by the various schools of classical archaeology was taking place throughout Greece (e.g. the American School of Classical Studies was excavating in the Athenian Agora and at Corinth, the German Archaeological Institute at Olympia, the French School of Athens at Delphi and Delos). As Director of the British School, Humfry Payne was searching for a new site for the British School to investigate in the years leading up to its fiftieth anniversary, and he eventually decided on the site of the Heraion (i.e., the Temple of Hera) and the harbour at Perachora, a remote and little known site in the Peloponnese. Perachora (meaning “the country beyond”) refers to its location across the Corinthian Gulf from the site of ancient Corinth. A lighthouse stands today on the bluff above the site as it did when Payne first went there, and it can be seen from Corinth.

Perachora

The village of Perachora is some ten kilometres from the site, and in the 1930’s there was no road between them. Villagers who worked at the site travelled there on foot, and supplies were brought in by donkey or boat. The archaeological site (also familiarly called Perachora) dates from the ninth century BCE and was occupied well into the Roman period. Although scholars knew of the site, it was considered too remote and too much a “backwater” to be worth investigating.Payne and his colleagues thought otherwise and in 1930 began systematic excavations there. The next four years produced a rich output of artefacts which were sent to the National Museum in Athens. Powell was able to join her husband and the team for three of the four seasons of the excavation.

Dilys Powell describes Perachora as “the heart of my Greece” and, while the book has many layers, she returns again and again to her memories of the dig and the villagers from Perachora who worked with the British team. She recalls with great fondness and also with a sense of unsentimental grieving — Payne met an early death in Greece in 1936 — her experiences of being a part of the excavations and her encounters with the villagers.

Map of Greece with Perachora

Payne’s untimely death put a temporary end to Powell’s connection with Greece.It was not until 1939 that she returned, but World War II prevented any further travel there until December 1945, when she again travelled to Athens and to the village of Mycenae, a special place for the two of them, which she chose for her husband’s burial. His tombstone in the village cemetery bears the words “Mourn not for Adonais”. She also returned to Greece in 1953 and 1954, and woven in with the accounts of the actual excavations at Perachora are her memories of all those visits and travels. Again and again she meets with the villagers of Perachora and others who describe their experiences in the Second World War, the guerilla war of 1946-1949, and the political conflicts and economic realities of the time. These accounts provide us, the readers, with personal descriptions of mid-twentieth century Greece, a time of considerable social change and disruption to people’s lives. Powell talks of her personal conflicted reactions to the changes she hears of and observes.

In her visits in the early fifties to Perachora, Powell relates an amusing account of a conversation with one of the villagers named Kostas, who, as a young man, helped out with the excavation. Kostas reminds her of a party held at the excavation site. The language she uses to report his and others’ accounts serves to make the stories even more alive for us because she turns the formally polite but rustic Greek of the villagers into a kind of archaically formal English: “At night it was, we ate, we drank, we danced — near one of the pits of the excavations we were, and thy husband the director fell in….I too fell into the pit at the same time” (p. 267).

Powell also returned to the village of Mycenae in the fifties, staying again in “The Fair Helen,” as she calls it (the famous Belle Hélène, which — interestingly — is still operating there today). She relates conversations with family members who own the inn, and she of course visits the grave of Humfry. She never speaks directly of her deep sadness over the loss of her husband, but that sadness is profoundly felt by the reader: “…I asked myself once again after all the years whether I had been right to choose Mycenae. And once again I thought that one could not have wished for a nobler grave” (p. 151). Powell also describes visiting the Tomb of Agamemnon at the archaeological site, and she remarks: “Through the doorway of the tomb came the sounds of the world: sheepbells, insects humming; life going on. I felt calmed, I felt steadied as I walked back to the inn; I felt changed. For the first time at Mycenae since Humfry’s death I thought only of the future” (p. 213).

In Plato’s Apology Socrates is reported to have remarked that the unexamined life was not worth living. Underlying Powell’s accounts of her travels in Greece and of the people she meets is a journey of self-discovery. She writes: “When I search in my memory for the forms of the past it is as if I were leaning over a sea-pool among the rocks” (p. 22). This is especially evident in the last part of the book. Powell is invited as a journalist to join with the British School to report on an excavation at the site of Emporio on the island of Chios. She contrasts this experience with being part of the excavations at Perachora some twenty years earlier. In her memories and insights, she seems to be able to come to a peaceful reconciliation with Perachora and all its associations and with Greece.

If you are a lover of Greece, both of its ancient past and more recent history, and you are enthusiastic about classical archaeology, Dilys Powell’s An Affair of the Heart will be a delight for you to read — and perhaps even to re-read many times.

Beer’s Blog

Josh has been very busy these past months. Here in Ottawa under the auspices of the College of the Humanities he gave a dramatic reading on September 17that the Fox and Feather Pub of Book 9 of the Odyssey, “Odysseus and the Blinding of Polyphemus, the one-eyed Cyclops”, once again using Peter Green’s recent translation. He then travelled to Athens at the invitation of the Canadian Institute in Greece where he gave a lecture on October the 17thentitled “The Athenian Plague and Eros as a Killer Virus in Euripides’ Hippolytus”.

Josh has been very busy these past months. Here in Ottawa under the auspices of the College of the Humanities he gave a dramatic reading on September 17that the Fox and Feather Pub of Book 9 of the Odyssey, “Odysseus and the Blinding of Polyphemus, the one-eyed Cyclops”, once again using Peter Green’s recent translation. He then travelled to Athens at the invitation of the Canadian Institute in Greece where he gave a lecture on October the 17thentitled “The Athenian Plague and Eros as a Killer Virus in Euripides’ Hippolytus”.

Nonetheless he has still found time to compose another blog, the subject of which is the well-known classicist Mary Beard. You may know of her not just from her books (e.g. S.P.Q.R. and Women & Power: A Manifesto) and blog, “A Don’s Life”, but also from her BBC documentaries on the Romans and their world. Let Josh tell you the story of how it came about that Mary Beard gave a lecture here at Carleton a few years ago.

Mary Beard

Our Poet’s Corner

Readers of Corvus, the journal produced each year by the Students of Greek and Roman Studies know Colleen Dunn very well. She has been publishing her poems there for the past few years or posting them in the students’ lounge in Paterson. She has kindly agreed to include a new poem here in the newsletter.

Readers of Corvus, the journal produced each year by the Students of Greek and Roman Studies know Colleen Dunn very well. She has been publishing her poems there for the past few years or posting them in the students’ lounge in Paterson. She has kindly agreed to include a new poem here in the newsletter.

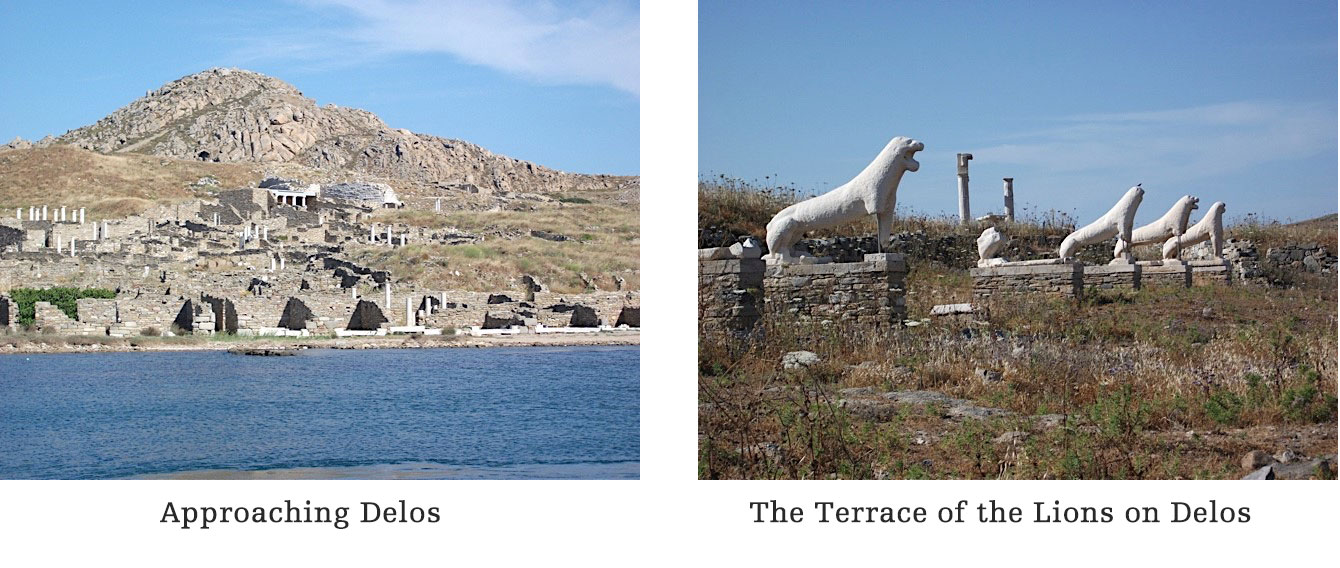

“Divine Isle” by Colleen Dunn

Resting silent in the turquoise sea, who am I?’

Warm winds and frothy sea mists brush my brow.

Encircled by Cyclades sisters I became

the bright and brilliant gem reflecting great Apollo.

Far-shooting god loved and feared by all!

Lone lovely goddess Leto plump with life,

I offered her safe harbour on my crescent shores.

Clasping clinging to the date all quivering fronds and palms.

Earth, eyes open, welcomed Zeus’ begotten.

I had no fertile fields of rustling grain.

Poor me I could not satiate a herd or flock,

but with Apollo’s footsteps buds bloomed where’er he tread.

Gloom passed, radiant future thus foretold.

Content and smiling, Leto she rejoiced!

I sung with her, by our melody our bond was sealed.

Behold a shrine sacred to Apollo rising up,

merchants and priests, fat fragrant sacrifice!

Small dusty me I prospered,

Who am I?

Friend to Leto, I am another mother to Apollo.

I am Delos, and proud to be.

by C. Dunn, April 2018

Donations

Donations to the Friends of Greek and Roman Studies are gratefully accepted and receipts will be issued. Donations are used for departmental events and honoraria. Thank you for your past contributions.

Acknowledgements/A Final Word of Thanks

I would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this Newsletter – both Susan Downie and Susan Treggiari, Pam Gahan, Colleen Dunn, and Josh. I appreciate very much the time and trouble you have all gone to at my behest.

I am happy to have contributions from any readers for the next issue and if you are interested, please do not hesitate to get in touch with me.

I would also like to thank Andrea McIntyre and Patricia Saravesi for all their organizational skills and computer wizardry in putting together this newsletter. It takes a lot of time and patience, to be sure.

The Very Best,

Marianne Goodfellow, Editor, FGRS Newsletter