Fleeing their home country’s civil war in 1991 brought more than 100,000 Somalis to a refugee camp in Da-daab, Kenya. They are still there, living in limbo. Confined by barbed wire, cut off from work, they are dependent on international assistance for food and health care, and perhaps, resolution of the problems that bring thousands more to the camp each year.

“In 1993, refugees waited on average nine years for a solution to their plight. Today, that wait is 18 years,” says James Milner, assistant professor in the department of political science. “There are some seven million people in the world living in prolonged exile. Refugees trapped in these situations typically live without legal status and are denied a range of basic rights.”

As a practitioner, policy advisor and researcher on issues relating to refugees, peace building, African politics and the United Nations system, Milner has witnessed the plight of protracted refugee situations, undertaking field research in Kenya, Tanzania, Guinea, Thailand and India. He will spend the summer back in Tanzania working with government, community leaders and non-governmental organizations as the country works towards the naturalization of 170,000 Burundian refugees who have been there since 1972.

“Governments need to see the broader picture linking refugees to other foreign policy issues such as security and development, and to reconceptualize how they engage with refugees,” Milner says. His research and work with the University of Oxford-based PRS Project is to provide a comprehensive analysis of the problem of protracted refugee situations; develop a more effective policy framework for addressing the problem; integrate the resolution of chronic refugee problems with issues of peace building, human rights, and sustainable development; and engage stakeholders in individual situations to formulate and implement solutions-oriented approaches.

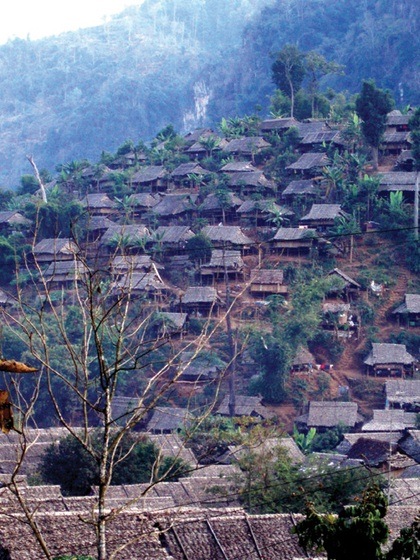

The Mae La refugee camp in Thailand, on the Thai-Myanmar border, is one of nine camps accommodating 48,000 people. Canada accepted 810 of these refugees in 2006-07.

In Canada, Milner hopes to strengthen the refugee researcher community in Ottawa as a base for ongoing discussion with practitioners, governments and organizations such as the United Nations. He’s excited to work with Carleton’s Research Resource Division for Refugees (RRDR), which has a long history and relationship with Canadian practitioners.

While the majority of the world’s more than 11.4 million refugees come from—and remain in—countries of the southern hemisphere, Canada annually resettles 10,000 to 12,000 refugees. The settlement, adaptation and integration of immigrants and refugees into Canadian society are a focus for the RRDR, which specializes in research and publishing on immigration and forced immigration.

Now housed in the school of social work, the RRDR was established in 1985 after the humanitarian crisis of Southeast Asian “boat people”. When more than one million refugees fled the war-ravaged countries of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, the Canadian government accepted 60,000 refugees between 1979 and 1980. The RRDR’s main research was to conduct longitudinal studies of the adaptation of the Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. The RRDR also provided comprehensive socio-cultural profiles of ethno-religious groups to help the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) make more informed decisions.

“The RRDR brought a research component the federal government didn’t have at the time,” says Adnan Türegün, executive director. “We played an essential role in building the IRB’s capacity and educating members of the board and people working in the sector.”

Today, the RRDR continues the knowledge-transfer function, also helping the settlement sector build capacity. With Saint Paul University and the Refugee Forum at the University of Ottawa, the RRDR is a founder of the Ottawa Migration and Refugee Research Network, an inter-university initiative to improve communication and collaboration among Ottawa-based researchers working on domestic and international issues broadly relating to migration and refugees. The network is currently conducting a mapping exercise to better understand the size, scope and needs of the migration and refugee research community.

Already, the RRDR has been instrumental in strengthening the settlement service sector. INSCAN (International Settlement Canada), a quarterly publication of the RRDR founded in 1987 and the website Integration-Net (integration-net.ca) provide forums for information sharing, discussion and research on topics related to settlement, adaptation and integration of immigrants and refugees.

“The RRDR is an important venue of communication between policy makers and the settlement sector,” says Behnam Behnia, academic director and associate professor. “We connect practice to policy and research in a concrete way.”

For refugees who have spent years not knowing where their futures lay, having researchers like Milner and networks like the RRDR influencing policy makers and facilitating their transition to society could mean the difference between a life in limbo and a solution to their plight.

Next ..