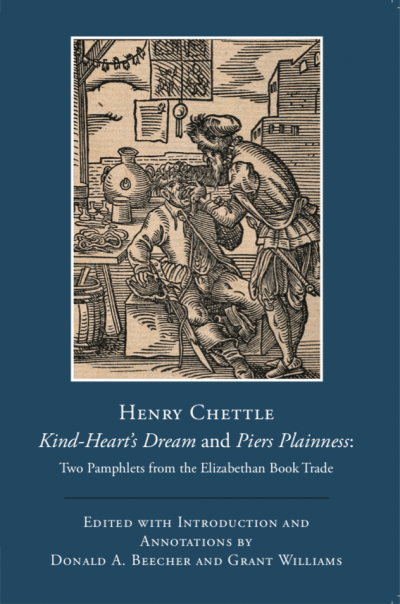

Professors Donald Beecher and Grant Williams have recently published an edition of two literary pamphlets written by the little-known Elizabethan printer Henry Chettle. (A pamphlet was a popular and cheap print form that could span anywhere from several pages to the length of a short book.) The first text, Kind-Heart’s Dream, is a parodic ghost story narrated by Kind-Heart, an itinerant tooth-drawer–that is, a vagrant who pulls out rotten teeth for a living. Five ghosts visit the narrator in his sleep to request that he help them by publishing their spectral letters to the world. Each of the ghosts represents its former profession: a ballad singer, a medical practitioner, a pamphlet writer, an actor, and a conman. The pamphlet reproduces the ghosts’ five epistles as though Kind-Heart has accepted their petition. The humor of the pamphlet comes from the polemic and diatribe that each epistle writer levels against the trespassers who threaten the integrity of his respective industry.

The second text, Piers Plainness–also with a title designating the narrator–tells the tale of a royal family exiled from their homeland of Thrace by the king’s traitorous son. During the civil unrest, Piers, an honest apprentice, passes from one crooked master to another and eventually stumbles into the opportunity of helping the royal family to regain their lost kingdom. Chettle weaves together two plots of different genres: one plot unfolds the trials and tribulations of the royal family according to romance conventions and the companion plot follows the narrator’s misadventures according to picaresque conventions. (The picaresque is a genre that chronicles a first-person narrator’s struggles to survive by his wits in a hostile urban environment.)

These two pamphlets allow contemporary readers entry into the world of itinerant labourers from the seldom represented vantage point of a humble tradesman. After apprenticing to a London printer, Henry Chettle became a member of the Stationers’ Company, the early-modern trade guild of printers, booksellers, and publishers. Since he never established his own business, he made ends meet by cobbling together various printing-house tasks and journeyman-roles, which sometimes meant composing pamphlets. His wonderfully imagined storytellers thus give voice to lowly Londoners who, like himself, struggled to find employment in a tight labour market controlled by the livery companies. The narrators who exist outside the official trades must scrape together a living while defending their vocational integrity from competitors. Throughout their narratives, they exercise their ingenuity to send up the engine of commerce, the labouring classes, and unscrupulous masters. The pamphlets have much to teach readers about the ways in which the print industry profoundly shaped the production of Elizabethan popular literature, relying upon the toil of vagrants, apprentices, and journeymen, as well as masters, to get the word out. Not only do they enhance our understanding of book history but they also speak to the oft-neglected culture of the early modern precariat.