Why did Carleton’s special film screening and Q&A on the roots of hip-hop culture attract such a diverse audience, which included students and faculty, poets and artists, Muslim and Indigenous activists, as well as fans of 70s music who heard about the event on CBC radio?

- Because it’s 2016

- Because hip-hop culture was born in the diverse streets of New York, and thrives in diverse settings around the world

- Because there is a widespread desire to think more deeply about diversity, art and the academy

- All of the above

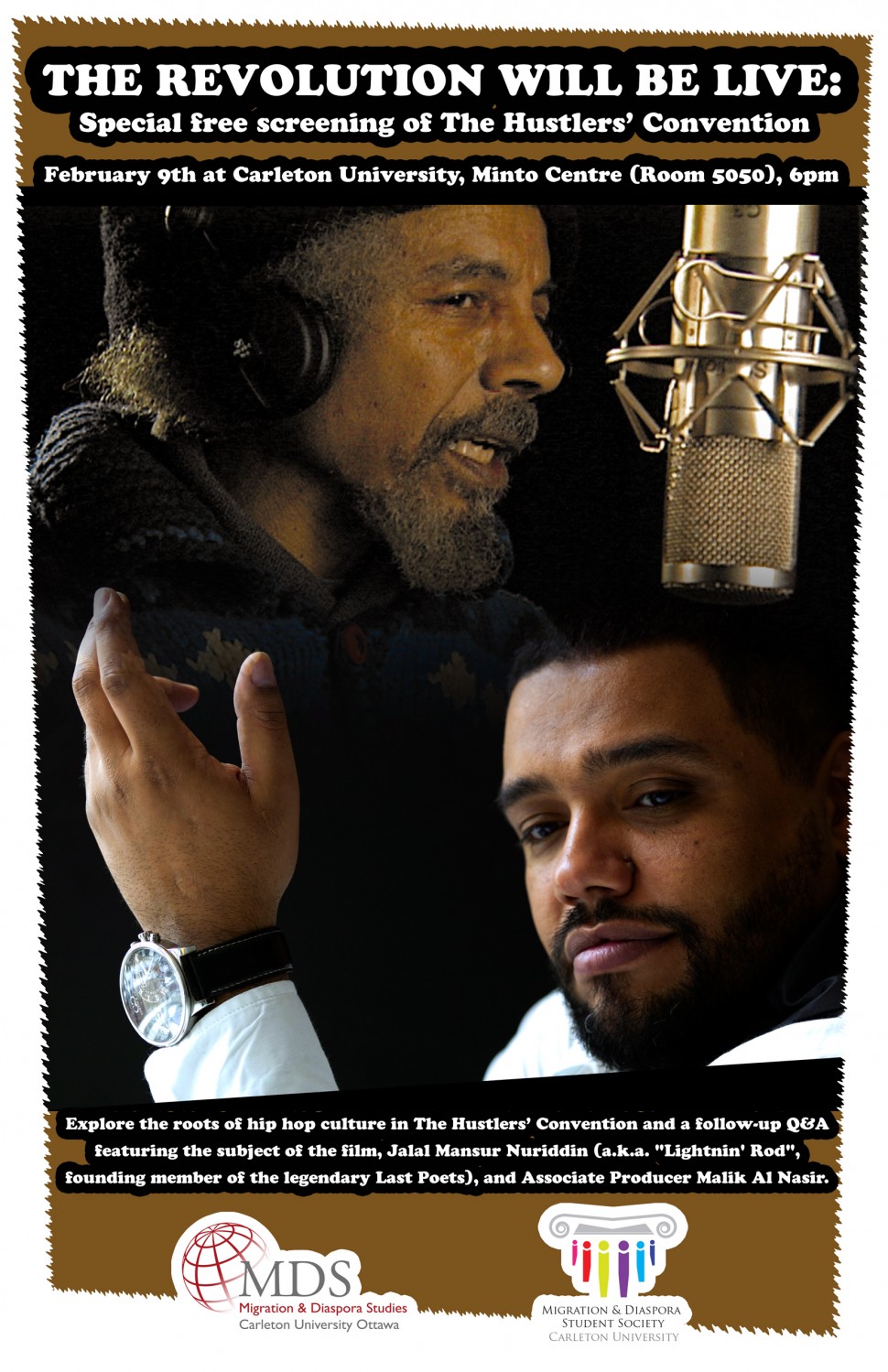

Carleton University hosted two guests during Black History Month who are renowned for their explorative, innovative and provocative work: Jalal Nuriddin (a founding member of the legendary Last Poets), and Malik Al Nasir (a poet shaped and encouraged by giants of the spoken word genre such as Jalal and Gil Scott-Heron).

Carleton University hosted two guests during Black History Month who are renowned for their explorative, innovative and provocative work: Jalal Nuriddin (a founding member of the legendary Last Poets), and Malik Al Nasir (a poet shaped and encouraged by giants of the spoken word genre such as Jalal and Gil Scott-Heron).

After delivering masterclasses and spoken word performances in Toronto and Ottawa, Jalal and Malik visited Carleton for a special screening of two films: Word Up from Ghetto to Mecca, a short film that goes on a poetic journey with Malik that crisscrosses across the Atlantic, and The Hustlers’ Convention, a new documentary that provides a unique insight into Jalal’s role in the evolution of hip-hop.

Two members of the audience, Daniel McNeil, an Associate Professor of History and Migration and Diaspora Studies who helped to organize the event, and Fazeela Jiwa, a community member and writer, shared their reflections about the politics and poetics of the evening with the FASS blog.

Q&A

Professor Daniel McNeil

Daniel: The event was called “The Revolution will be Live” in homage to Gil Scott-Heron, and his famous poem about a revolutionary spirit that would not be commodified or sold on television screens.

I hoped that the film would be an entertaining and enlightening portrayal of the history of hip-hop in the African diaspora, and help us to map examples of creative artistry that grew up in small town deprivation as well as big city isolation. I also expected that the Q&A would bring together students and faculty at Carleton who are interested in exploring a global present in which hip-hop is a lingua franca for young people around the world.

I didn’t anticipate the level of interest in the event from the wider Ottawa community, and I was fascinated by the ways in which people from various communities related to the stories of Malik and Jalal.

I’m still taking time to think through the range of issues covered during the Q&A. The public event spoke to so many important topics – from the deep connections between Islam and hip-hop, to the power of the arts to address the pain and suffering wrought by Canadian colonialism on Indigenous communities, to forms of Black Consciousness that are associated with a willingness to fight necolonial practice rather than skin pigmentation.

What were some of your hopes for the event Fazeela? And how did they relate to your experiences with art and public discourse in Canada?

Fazeela Jiwa

Fazeela: My hope, which was certainly fulfilled by the words I heard that evening, was to hear yet another way in which radical artistry both celebrates the community it rises from, and subverts the system that seeks to exploit it. This is the story of hip-hop and so many other art forms – they are born from political dissent and then become co-opted to reinforce the very thing they critique.

In a specifically Canadian context, inclusion, representation, recognition are things that many people of colour struggled for in Canada during the 70s, 80s and 90s. By now, I think it’s become clear that industries like producing or publishing or the academy are adept at co-opting any narrative to suit simplistic renderings of ethnicity because that is palatable and profitable.

Through observation and conversation I have recently come to believe that many artists of colour are disillusioned by the process of “inclusion” into the public discourse in Canada. I have noticed that ingenious people are, more and more, finding ways to communicate their art and their ideas to and for their own local, global, and virtual communities.

People are seeking out radical art that questions boundaries and institutions, and they name these connections decolonization – as a few folks did in their questions for Jalal and Malik. How to use art as one tool toward decolonization, they asked, and by even asking this I think they reach toward an anti-capitalist, anti-racist, equality-seeking art that reflects and creates a liberated world.

Daniel: Such reflections about the radical imagination, and the ways in which it can be appropriated by corporate forms of multiculturalism, also make me think about the struggles of the 1970s.

From Gil Scott-Heron reminding Americans that the revolution would not be televised and would not go better with Coke, and the anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko expressing concern about people from “Coca-Cola and hamburger cultural backgrounds” shaping cultural and political institutions in South Africa, I’m fascinated by global revolutionary protest in the 70s. It seems like the best of times and the worst of times. An age of musicians putting the UN Declaration of Human Rights in the hands of ordinary people, and an age of authoritarian populists waging war against the blues philosophy and DIY spirit expressed by reggae, disco, spoken word and punk.

But I’m also aware that many others would prefer to look forward and connect the global story of resistance in the 70s to our contemporary moment of #BlackLivesMatter, #OscarsSoWhite and the performance art of the Donald in North America, as well as the widespread attacks on forms of North American hip-hop that are deemed socially irresponsible.

How did you feel about the documentary’s attempt to position Jalal as the foundation for today’s hip-hop scene, and one of the missing links between Soul Power and hip-hop?

Fazeela: I appreciate the point made in the documentary that the Last Poets, The Hustlers’ Convention, and Jalal himself present the “missing link” that connects hip-hop to its revolutionary political roots. It’s definitely sad, to say the least, to see the co-option of these roots toward glorifying capitalism and class hierarchy in a lot of contemporary hip-hop.

But you can’t have revolution without dismantling patriarchy. The story of The Hustlers’ Convention, though well-worded and subversively critical of racism in the U.S, relies on the exploitation of “bitches” in the background of the “pimp,” and it didn’t really speak to the powerful women wordsmiths on the scene then or now. The Hustlers’ Convention as a poem, as well as the documentary about it, are very limited to a male narrative, so can’t be posited as the missing link because there’s still a lot missing.

Daniel: Thanks Fazeela. The perils of power, objectification and patriarchy bear repetition, especially when they help to remind us about the dangers of privileging male stories of pain, anger and validation as part of the “changing same” of hip-hop and Black History Month.

Inside and outside of the academy, we may have to curb our enthusiasm for contemporary celebrations of diversity that do not involve a concomitant resolve to revisit the missing pages of our historical accounts. If there is a desire to shame contemporary forms of corporate multiculturalism, we may also have to ask more questions about desires to interpret (and misinterpret) hustlers of the 70s, 80s and 90s as crusading and romantic anti-capitalists rather than rugged and self-motivated entrepreneurs. After all, the answers to our historical and contemporary questions may not only lie in taking the politics of hip-hop seriously, but in questioning those who treat the work of hip-hop artists too seriously and too literally.