Trudeaumania

In 2015, Canadians reacquainted themselves with the expression “Trudeaumania.” After ten years of Conservative Party rule under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the election of the Liberal Party of Canada leader Justin Trudeau as the nation’s new Prime Minister was celebrated by many as an overdue change for a country in need of a progressive makeover.

Through an election strategy which relied heavily on an extensive social media campaign and a thorough understanding of popular culture, Trudeau canvassed Canada making promises of national unity and progressive policy. This brand of modern idealism was accentuated by the fact that it came from someone who perfectly personified the message. Equipped with youthful looks and flawlessly tailored suits, Trudeau parlayed the LPC from its pre-election third party standing to a commanding majority government. This victory assured that Canada would experience at least nineteen years of Government under a Prime Minister Trudeau.

While the 2015 election victory may have felt fresh and progressive to Canada’s Millennials and Gen Xers, Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation were experiencing a dose of “Trudeaumania” déjà vu. In fact, anyone who lived through the original iteration of Trudeaumania is likely to contend that, compared to Pierre’s iconic rise to power, Justin’s ascension felt a touch conventional. As the saying goes, history never repeats itself, but it often rhymes. Bearing this mantra in mind, the recent book by Paul Litt (Department of History and School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies), Trudeaumania, has arrived at a particularly timely juncture in Canadian history.

Trudeaumania, which has been released to tremendous critical praise, is Litt’s examination of the public excitement and enthusiasm that distinguished the rise to power of Pierre Elliot Trudeau in the late 1960s. Trudeaumania is a must read for many reasons, but what makes it a particularly unique analysis is Litt’s detailed deconstruction of the influence of the radical and celebrated popular culture of the era on the phenomenon of Trudeaumania. Movements like the civil rights crusade had laid the groundwork for social justice activism. Protests against the Vietnam war were mushrooming. By 1968, the counterculture was in full blossom — a feisty mix of idealism and hedonism, all set to a rowdy rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack. Litt calls it “a carnival of indulgence, defiance, and iconoclasm besieging the bastions of convention,” adding that “As protest movements and the counterculture merged into a mad torrent, the threat of radicalism loomed large.” The convergence of this fabled spirit of the sixties with rising nationalist sentiment in Canada set the context for Pierre Trudeau’s rise to power.

There are two main characters in Trudeaumania — Canada in the 1960s and the Trudeau it imagined. Litt approaches this pair with the premise that you can’t understand one without understanding the other.

“I’ve been interested in Canadian nationalism for years and came to see the late 1960s as a formative passage in its history. Smack in the middle was this odd moment when people seemingly went crazy over a novel politician,” Litt elaborates, “What was that all about? I wanted to figure out what was going on in Canadian politics in 1968, how Trudeaumania reflected its times, and whether it was more than just a passing fancy.”

National Identity in the Swinging Sixties

There are two main characters in Trudeaumania — Canada in the 1960s and the Trudeau it imagined. Evocative writing captures the colour of the times and the image of a self-realized, culturally-attuned Pierre Trudeau. “Canada unavoidably began the Cold War as a stalwart ally of the U.S. in its crusade to protect the free world from communism, but this sidekick role heightened fears that it had escaped from one empire only to be colonized by another,” Litt explains. “In the years leading up to the centennial, nationalist sentiment was cresting. Nationalists repeatedly proclaimed that Canada was ‘coming of age,’ undergoing something akin to an adolescent rite of passage, struggling to emerge as a mature nation.” There were intense debates about foreign ownership of the Canadian economy, American cultural imperialism, and Canadian identity.

The problems that afflicted the United States in the 1960s further encouraged Canadian nationalism. “As the 1960s wore on, the image of the U.S. suffered from the civil rights movement, its contribution to the spectre of a nuclear Armageddon, ghetto riots, political assassinations, and militarism run amok in Southeast Asia,” Litt avers. “As the Pearson government’s new social programs rounded out a welfare state more extensive and compassionate than that south of the border, the Americans’ image problems gave Canadian identity theorists the chance to define Canada, in contrast, as a polity distinguished by an innate moral immunity to all of the ills then afflicting the United States.” Positioning Canada as a “Peaceable Kingdom” made it look good compared to an America that was increasingly associated with conflict, militarism, and violence. Trudeaumania shows how this identity theory affected contemporary discourse concerning Canada’s character and future. As Litt puts it, “The Peaceable Kingdom was conceived in schadenfreude.”

The idea of Canada as the “Peaceable Kingdom” emerged out of nationalists’ efforts to construct an identity befitting an autonomous nation. It was designed to make Canada look good compared to an America which was increasingly associated with conflict, militarism and violence.

Canada: 1967

The centennial year was a critical prelude to Trudeaumania. In 1967, Canadians from all corners of the land became engaged in activities that heightened their sense of national community. These commemorations stressed Canadians’ hundred years of shared history, giving the national community a venerable pedigree. But nations need to have a future as well as a past, and it was here that Expo 67, the world’s fair hosted by Canada that year, made a signal contribution. “It was futuristic, projecting an image of a nation on the cutting edge of modernity,” Litt maintains, “It complemented the centennial’s inward-looking unity-and-identity preoccupations with an outward-looking cosmopolitanism.” Best of all, it was a smash hit, winning Canada praise from around the world. Canada, it seemed, had stepped into the world spotlight with a dynamic new image and earned a place of distinction in the international community. It is rare for a nation to affirm its identity and win world-class status in one stroke, Litt argues, but Expo 67 was such an achievement, and it pushed nationalist pride to dizzying heights. “The next natural step was to look for some means of institutionalizing the high.” Voila: Pierre Trudeau. As one young voter put it, “He’s the type of man who should follow Expo ’67 and be a vital part of the new, identifiable Canada.”

Litt continues: “Even as they were liberating Canada from its colonial past and resisting re-colonization by the United States, Canadian nationalists faced the grave threat of a rising separatist sentiment in Quebec during the 1960s.” Trudeau’s years as a caustic critic of the Duplessis regime in 1950s Quebec made him an anti-nationalist. In the wake of the Quiet Revolution, a new Québécois nationalism promoting the province’s government as a French-Canadian nation state was on the rise. By 1967 there was a consensus among Canada’s three leading political parties, based on a ‘two nations’ view of Canada, that nationalism in Quebec would have to be accommodated by conceding the province some special constitutional status. Then suddenly Trudeau appeared on the scene, challenging that consensus with a principled, logical defence of symmetrical federalism. Ironically, this made him a hero to Canadian nationalists. Not only would he move the nation ahead, but he would also keep it together.

The Media’s Role

Most voters came to know Trudeau through the media. Thanks to their increasing penetration into daily life — particularly, the prevalence of television in the family home — it was easier for Canadians to feel directly engaged in national affairs. Canadians may now have belonged to a ‘global village,’ as another renowned Canadian and friend of Pierre Trudeau famously articulated, but they were also part of a ‘national village’ with which they identified strongly. Moreover, as Canadian television producer Richard Nielson wrote at the time, “no medium in history creates the taste for the real-life drama that TV does.” The conditions for a national mania were in place.

Trudeau rose to national prominence in the final weeks of 1967, just as Lester Pearson announced his retirement, launching a Liberal leadership contest. “Trudeau was a great media performer in a variety of ways, especially on television, which had become the primary means by which most Canadians followed politics,” Litt continues, “He had that certain je ne sais quoi that gives someone onscreen presence. But that wasn’t all. He did stunts like sliding down a bannister or staging a pratfall, providing the visual action the medium demanded. All of this helped make him a political star.”

Many journalists were deeply invested in the nationalist project of seeing Canada come of age as an exemplary modern nation. Identifying Trudeau as an appropriate figurehead for this project, they presented him as a new breed of politician, a swinger in step with the times, “a leader who could personify Canada as they wished it to be,” as Litt puts it. The “mod” style then trendy in the fashion world offered the perfect pop culture mode with which to brand their project. The moral high ground Canadian nationalists staked out for Canada was much the same as that from which sixties radicals critiqued the establishment. Yet most weren’t radicals — on the contrary, they had a vested interest in the status quo. They channeled the spirit of the sixties to expedite national renewal, but they wanted progressive reform, not revolution. Mod was the perfect aesthetic mode for signaling an urgent but moderate change.

The media portrayed Trudeau as a youthful, articulate sex symbol who appealed to the spirit of the times by promising change. Unmarried, and thus conceptualized as ‘free,’ Trudeau, with his comb-over and acne scars, exemplified an emergent “new masculinity.” Canadians were drawn to Trudeau’s undeniable coolness and charm, and his overt intelligence jibed with the counterculture’s quest for enlightenment. At the same time, Trudeau’s intellect empowered him to practice a new type of politics that would apply, dispassionately, a modern managerial approach to contemporary problems. The late sixties might have been the one moment in Canadian history when being perceived as an intellectual had more positive than negative connotations. ‘Reason over passion’ was part of Trudeau’s cool image, another way in which he promised to be an agent of national modernization.

While Trudeau’s intelligence was part of his sex appeal, it was accompanied by more conventional image-making. The Prime Minister-in-waiting drove a Mercedes convertible and wore a flower in his lapel. Maclean’s magazine proclaimed Trudeau an “story_intro_authoritative judge of wine and women.” “In the context of the times, Trudeau’s sexiness sent an important signal,” says Litt. “The sexual revolution led and symbolized the many liberation movements of the sixties. Denoting Trudeau as sexy implied that he was in step with the times—the man to update Canada.” When, late in 1967, Minister of Justice Trudeau liberalized laws affecting divorce, abortion, his image as a hip modernizer was substantiated.

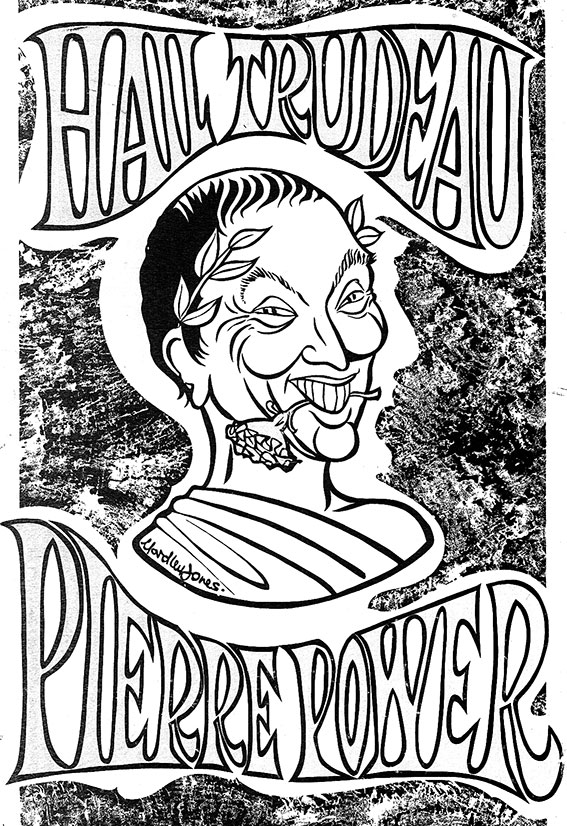

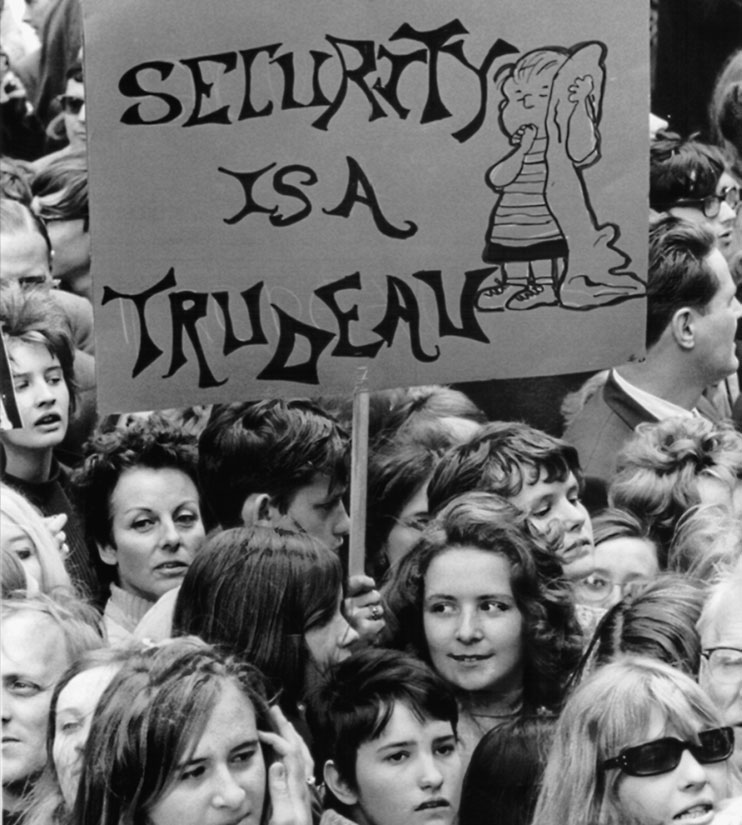

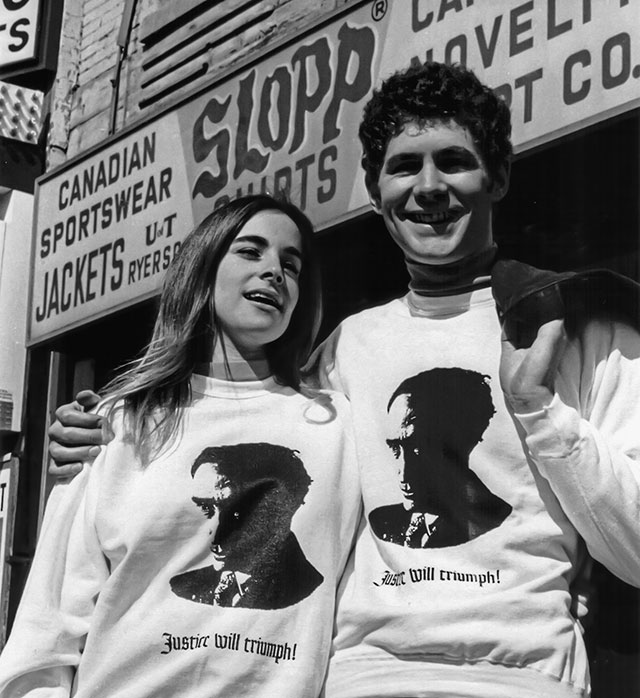

Today we are familiar with celebrity politicians, but Pierre Trudeau was Canada’s first experience with the phenomenon. As Trudeaumania snowballed in the early months of 1968, it generated all the ephemera typical of a pop culture fad, including posters, dresses, sweatshirts, and pop songs. When he started his research over a decade ago, Litt didn’t have to look far to find an example—it came from Professor Allan J. Ryan, whose office was just down the hall in the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies. In a previous life as a folk singer, Ryan had a hit in 1968 with his song PM Pierre. Other examples of Trudeaumania pop were harder to track down. “It was fun unearthing it all,” says Litt, “Much of it was amusing, and some of it was elusive, but I just kept following leads until a full picture emerged.”

Along the way Litt picked up on the fact that many Canadians were deeply uneasy with the entire process. “This was the age of McLuhan, and people were debating in earnest the effects of the media in society generally and in politics in particular,” Litt says, “Were they delivering the real goods? Could their representations of people and events be trusted?” Addressing this concern, Trudeau regularly made a point of calling attention to the media’s role as an unreliable messenger between him and his audiences, reassuring them that he was just as skeptical as they were about their means of communication. He would coyly pause before answering a reporter’s question, often responding with a sly grin or wink, letting the audience in on the joke. His intuitive post-modern sensibility dispelled doubts about his image and reassured audiences that he was authentic. “I feel like a Beatle. Not that I have anything against the Beatles, but is this the way to choose a leader?” Trudeau poignantly asked Saturday Night magazine in 1968. Comments such as this reassured Canadians that he shared their concerns and was, despite their mutual dependence on the media, a strong character rather than a mere media personality.

One of the great strengths of Trudeaumania is its dedication to providing the reader with meticulous context. Litt provides a nuanced and objective reconstruction of the phenomenon, demonstrating how Trudeau was portrayed as a youthful, articulate sex symbol who appealed to the spirit of the times with promises of profound change.

The nature of modern political campaigning also worked to quiet mediation anxiety. “When you think about it, politicians are very much like pop stars when they tour during elections,” observes Litt. “The live appearance of a figure previously known only through the media proved he was real and linked local communities with the community of nation, again alleviating anxiety about the media’s intermediary role in national politics.” Concerns about the press were part of a more general anxiety about living in a mass society afflicted by the malaise of individual alienation. “He restores to each of us a sense of individual worth. We are no longer insignificant members of a mob, all running in the same direction because our leaders tell us to,” one journalist claimed. “He wants . . . to release us from servility to mass machines created by others, from the dominance of self-appointed elites who think they know better than we do what is good for us.” Wow! Trudeau was now the politician-as-panacea, a cure for all the ills of modernity. “In a sense,” another journalist explained, “he has been adopted by a society unhappy with grey corporatism and worried about the all-embracing bureaucracy, and puzzled if not fearful over the coming dehumanized, technological culture.”

Trudeaumania 2.0?

Through meticulous research and revealing insights, Trudeaumania evokes one of the most fascinating eras in Canadian history and the iconic personality to which it gave rise. Does it also have some functionality as a tool to understand Canada’s contemporary political reality? Litt cautions that the late sixties were “a very particular era in which the factors in play were distinctive and interacted in different ways.” For this reason, applying the term Trudeaumania to Justin’s rise to power is misleading. The circumstances in which they came to power were unique. Pierre Elliott Trudeau had been in federal politics for less than two-and-a-half years and a cabinet minister for less than a year when he announced his candidacy for the Liberal leadership. Six weeks later he was prime minister, and two-and-a-half months after that he won a majority government. He was front and centre in political coverage and a clear favourite throughout his rise to power. In 2015, Justin, in contrast, had been a prominent figure in the Liberal party for years and its leader for over two years. The focus of the 2015 election was initially more on the other leaders and expectations of him were relatively limited. Moreover, the personalities of father and son seem quite distinct. Pierre was famously aloof, even arrogant, while Justin likes to mingle and showboat the common touch.

People are instinctively curious about historical precedents for present-day phenomena, so it is inevitable that 1968 and 2015 will be mined for similarities. Litt concedes that “Many of the same influences were at work—the role of the media in sustaining the nation, the politics of image, the invasion of politics by features of popular culture such as fashion and celebrity, the notion of Canada as a kinder, gentler America, and a politician whose success derived from all of these factors. So 1968 is in many ways recognizable to us today.” Like his father, Justin is an adept performer in the media, even though the media complex is vastly different today. He too is seen as a sex symbol. Both father and son had trendy images and won elections by appearing as agents of change when the electorate was impatient for change. Both were dismissed as dilettantes yet revealed an underlying discipline, determination and work ethic. The relevance of history is further suggested by considering the likelihood of Justin Trudeau becoming prime minister if his father had not preceded him in that office.

Published in October 2016, Trudeaumania has a lot to say about the power of celebrity in electoral politics, a topic of some interest since last fall’s U.S. presidential election. More generally it offers insights into factors that characterize politics in a modern mass-mediated democracy over the long term. Litt hopes his book will also enhance our understanding of Canadian nationalism, in particular how a persistent Canadian identity myth was forged in the unique circumstances of the sixties. In 2017, we are celebrating Canada’s 150th birthday, an anniversary that recalls Canada’s centennial celebrations in 1967. Trudeaumania suggests that events fifty years ago could be interpreted as the birth of modern Canada. “You could say that Canada’s formative sixties are embodied in our current choice of a prime minister,” Litt adds, “When Justin Trudeau said ‘Canada is back,’ it was his father’s Canada that he was invoking.”

Trudeaumania is a vital read for anyone interested in Canada past or present. This article can only provide some tantalizing glimpses of its fascinating period detail. Nevertheless, it is impossible to resist ending this piece where Trudeaumania the book begins — with the evocative lyrics of Allan Ryan’s PM Pierre:

(listen here MP3)

There’s a new infatuation that’s been sweepin’ the nation

Shakin’ the roots in the ground

Of an old generation, a new inspiration

Takin’ a new look around

But he’s quickly disarming and utterly charming

Quite enough to make you let down your hair

In a Society Just, a society must

Check out PM Pierre

PM Pierre, with the ladies, racin’ a Mercedes

Pierre, in the money, find him with a bunny

Pierre, a little brighter than the northern lights

He oughta add a lotta colour to the Ottawa nights

Charismatic and dynamic with a trans-Atlantic flare

Regardez PM Pierre

— PM Pierre by Professor Allan J. Ryan (Indigenous and Canadian Studies, Carleton University)

(listen here MP3)

Trudeaumania is published by University of British Columbia Press and can be found at most major book dealers.

Up Next for Litt

Professor Litt’s next project, “Motoring into Upper Canada,” is a history of the Ontario heritage establishment in the 1950s and 1960s that focuses on the interface of ambitious technocracy and unruly collective memory.