by Nathaniel Whelan

The impacts of climate change in the Arctic are deeply concerning. The region is warming at a rate three times higher than the global annual average, with increasingly catastrophic consequences. While the persistent rise in temperature has given way to countless threats, one of the biggest has become the rapid and widespread thaw of Arctic permafrost.

Who does this impact? What actions can we take? And what role does Carleton University play in addressing this crisis?

Permafrost Thaw and Climate Change

Permafrost is a sublayer of frozen ground that covers roughly 15% of land in the Northern Hemisphere, including more than a third of Canada. It is ground that remains at or below zero degrees Celsius for two or more years, and plays an essential role in protecting polar ecosystems and reducing carbon emissions.

There is approximately 1.4 trillion tons of carbon in Arctic permafrost soils, absorbed mostly from dead plants unable to decompose. As northern regions grow warmer, permafrost begins to break down, releasing the once preserved carbon into our atmosphere, creating an imbalance within our planet’s natural carbon cycle.

Carbon emissions from permafrost thaw are expected to be anywhere from 30 to more than 150 billion tons by the year 2100. This severe uptick of such a potent greenhouse gas, in addition to methane, contributes to the drastic acceleration of global climate change.

The damage caused by greenhouse gas emissions from thawing permafrost is irreversible. It can lead to sea level rise, wildfires, droughts, forced migration, and even disease as ancient bacteria and viruses are released. More immediately, it transforms the Arctic landscape, driving landslides, destroying infrastructure, and impacting whole communities, with an estimated 3.6 million people directly living in vulnerable areas.

Despite our understanding of the severity of the situation, there is still a significant gap in our knowledge about greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost thaw. This is largely a result from a lack of Arctic carbon monitoring.

Drs. Elyn Humphreys and Murray Richardson are looking to fill that gap.

Monitoring Permafrost and Policymaking

Early in her career, Elyn worked on quantifying the carbon cycle of Canada’s managed forests, putting numbers to important questions, such as the release of carbon dioxide from harvested forest lands and the carbon balance of regrowing forests. Motivated by the rapid warming of the circumpolar regions, she decided soon after to shift focus to the Canadian Arctic.

Similarly, Murray has shifted his interests from studying mercury in boreal regions to water security issues affecting Canada’s Arctic and Subarctic communities.

Now long-standing professors at Carleton in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, both Elyn and Murray have teamed up with Permafrost Pathways, an internationally funded network of climate scientists, environmental justice experts, Indigenous knowledge holders, and policymakers, all collaborating on adaptation and mitigation strategies that address the ongoing permafrost crisis.

Funded by the Woodwell Climate Research Center, Elyn and Murray have turned their attentions to Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, to contribute to the monitoring of greenhouse gas emissions from tundra ecosystems and the underlying permafrost.

Speaking to the importance of this, Elyn said:

“The field data we collect is critical to help develop and evaluate Earth system models that we use to predict future climate scenarios.”

In the past, the emissions from permafrost thaw have either been miscalculated or omitted completely from global carbon budgets as a result of all the uncertainty. By improving our efforts in monitoring and modelling, this new coordinated pan-Arctic network will provide local leaders, national policymakers, and other international bodies with the data to incorporate permafrost thaw emissions into our collective efforts to combat climate change.

It will also help create a framework to ensure that threatened Arctic residents have the necessary resources to confront the hazards stemming from permafrost thaw and to limit future harm to their overall well-being.

Measuring Arctic Carbon

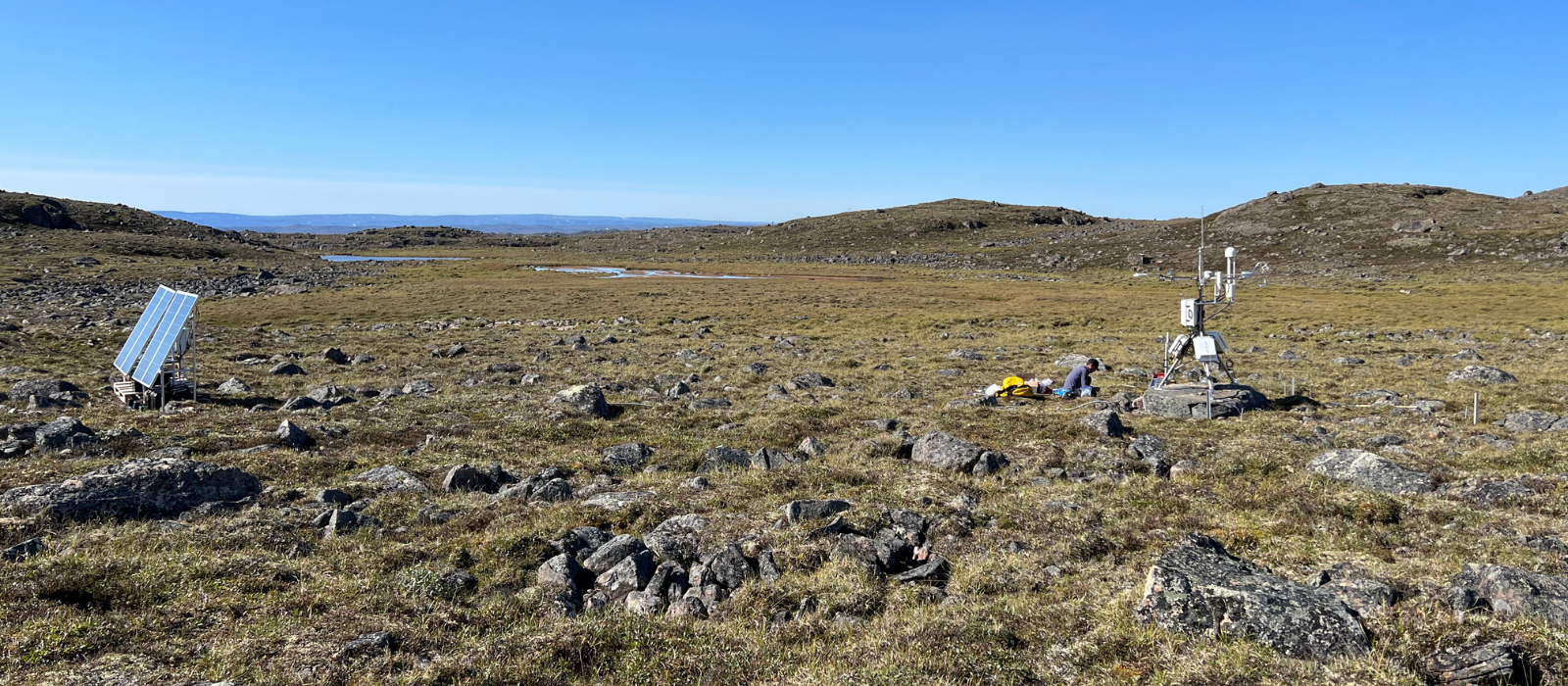

Flux towers are observational instruments that measure the exchanges of carbon dioxide, methane, water vapour, and energy between the biosphere (where life exists on Earth) and the atmosphere.

To quantity the carbon cycle, Permafrost Pathways has established new towers in regions that are not already well represented in the data. They are also working with local experts to expand the number and coverage of these towers. This includes contributing new equipment and logistics support to Elyn and Murray’s team so they can measure carbon dioxide and methane fluxes year-round in the rocky tundra environment just outside of Iqaluit.

Since the tower measures water vapour exchanges as well, the project also advances Murray’s ongoing hydrology work with the city, which supports long-term municipal water supply planning in this water-stressed Arctic community.

On top of her work in Iqaluit, Elyn monitors carbon fluxes from other northern locations affected by permafrost thaw, such as the Hudson Bay Lowlands of Ontario and in the Northwest Territories. While high frequency data is collected in person, many of her flux towers are equipped with cell or satellite service, which allows Elyn to download much of the data directly to her computer here at Carleton.

When asked how the experience has been so far, she said:

“Very good! The new equipment is up and running, and we are excited to start analyzing the data and adding it to the Permafrost Pathway datasets for ongoing synthesis activities.”

Elyn and Murray’s work in Iqaluit is funded until the end of 2027. After 4 years of measurement, they will have enough data to determine whether or not that tundra emits more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than it absorbs, helping improve an international assessment of the Arctic carbon balance.

Conclusion

In addition to teaching, Elyn and Murray are working with the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun on community-led projects related to water quality and wetland management. Elyn is also currently studying the carbon cycles of peatlands and wetlands in temperate regions, including Mer Bleue in Ottawa and restored marshlands in Southern Ontario.

Both researchers travel north several times a year to continue their ongoing work in the Arctic.

Follow the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies on Twitter to learn more about exciting research that has long-term, positive impacts on our planet.