By Calum Carmichael.

By Calum Carmichael.

(The full, five-part series is downloadable as a pdf: What Can the Philanthropic Sector Take from the Downfall of Samuel Bankman-Fried and His Ties to Effective Altruism, a five-part series by Calum Carmichael (2023).)

Part 4: Questioning the analytical methods of Effective Altruism

Introduction

Late in 2022 the bankruptcy of FTX International and the criminal charges brought against the crypto entrepreneur Samuel Bankman-Fried (SBF) re-focused and intensified existing criticisms and suspicions of Effective Altruism (EA) – the approach to philanthropy with which he was closely associated. Part 1 of this series placed those criticisms under seven points: two each for the philosophical foundations and analytical methods of EA, and three for its ultimate effects. Part 2 described EA: its origins, ethos, analytical methods, priorities and evolution. Part 3 focused on the two criticisms and their rejoinders that apply to its philosophical foundations, and part 5 will do the same for the three criticisms that apply to its ultimate effects. Here in part 4, I focus on the two criticisms that apply to the analytical methods. Of those, I pay particular attention to the first, given that it introduces material picked up by the other two. Before discussing each, I provide several references to it made following the downfall of SBF.

Late in 2022 the bankruptcy of FTX International and the criminal charges brought against the crypto entrepreneur Samuel Bankman-Fried (SBF) re-focused and intensified existing criticisms and suspicions of Effective Altruism (EA) – the approach to philanthropy with which he was closely associated. Part 1 of this series placed those criticisms under seven points: two each for the philosophical foundations and analytical methods of EA, and three for its ultimate effects. Part 2 described EA: its origins, ethos, analytical methods, priorities and evolution. Part 3 focused on the two criticisms and their rejoinders that apply to its philosophical foundations, and part 5 will do the same for the three criticisms that apply to its ultimate effects. Here in part 4, I focus on the two criticisms that apply to the analytical methods. Of those, I pay particular attention to the first, given that it introduces material picked up by the other two. Before discussing each, I provide several references to it made following the downfall of SBF.

Throughout, my goal isn’t simply to present contending views on the foundations, methods and effects for EA, but to derive from them implications and questions for the philanthropic sector as a whole – so that regardless of our different connections to the sector, we can each learn or take and possibly apply something from the downfall of SBF and his association with EA.

Criticism 3: By relying on impartial reason to identify the philanthropic interventions that will do the most good, EA idealizes a methodology that quantifies and compares the value and probabilities of alternative and highly-speculative outcomes – thereby mistaking mathematical precision for truth and ignoring important qualities of human life and flourishing that are not readily quantified.

“Effective altruism, perhaps because it comes out of the hothouse of the Oxford philosophy department, is a bit too taken with thought experiments and toy models of the future. Bankman-Fried was of that ilk, famously saying that he would repeatedly play a double-or-nothing game with the earth’s entire population at 51-to-49 odds.” —Ezra Klein, Dec 2022

“The question of how to do good cannot be divorced from questions of what is just and where does power reside. This is a matter of morality: people concerned with doing good should be thinking about themselves not just as individual investors but as citizen-participants of systems that distribute suffering in the world unequally for reasons that are not natural but largely man-made.” —Zeeshan Aleem, December 2022

As described in part 2 of this series, the analytical methods of EA rely on frameworks that distinguish and rank alternative causes and interventions. Both frameworks emphasize the quantification of outcomes and their probabilities. The first line of criticism against the analytical methods focuses on how the emphasis on quantification introduces types of methodological blindness that could either sideline certain matters relevant to well-being, accommodate subjectivity particularly in risk assessment or downplay the uncertainties and debates around “doing the most good” – the stated objective of EA.

Using common and quantitative units of account to compare the cost effectiveness of alternative causes and interventions automatically favours projects where data can be collected and causality tested: hence, matters of health in controlled environments get attention, whereas matters such as justice or self-determination are overlooked, as noted in part 2. Even for matters of health, preliminary studies based on, say, randomized controlled trials, provide imperfect guidance. Their results are specific to the scale and context of the trials and don’t readily generalize and transfer to other contexts. Moreover, the results don’t capture the experiments’ long-term effects that could counteract any positive ones observed early on.

Samuel Bankman-Fried

More generally, “[t]rying to put numbers on everything causes information loss and triggers anchoring and certainty biases…. Thinking in numbers, especially when those numbers are subjective ‘rough estimates’, allows one to justify anything comparatively easily, and can lead to wasteful and immoral decisions.” Expected value calculations are particularly prone to this by accommodating personal levels of risk tolerance as well as value judgments about outcomes and their probabilities. Hence, they could give cover for reckless but pet decisions if upsides are emphasized and downsides disregarded – something all the more likely in the hands of someone like SBF who welcomed risk:

“[T]he way I saw it was like, ‘Let’s maximize EV: whatever is the highest net expected value thing is what we should do’…. I think there are really compelling reasons to think that the ‘optimal strategy’ to follow is one that probably fails – but if it doesn’t fail, it’s great. But as a community, what that would imply is this weird thing where you almost celebrate cases where someone completely craps out – where things end up nowhere close to what they could have been – because that’s what the majority of well-played strategies should end with.”

Indeed, leaders of the EA community could claim similar cover for their decision to tie their fortunes and reputation to SBF in the first place: someone known as “an aggressive businessman in a lawless industry”.

The focus on quantification contributes to a methodology susceptible to not only narrow and reckless decisions, but also decisions that are misdirected or conflictual because of the confusion around what “doing the most good” actually entails. On that score, EA has boxed itself into a corner. If it remains exacting in how to define and measure “the most good,” then it increases the chances of repelling most donors and simply being wrong. Alternatively, if it offers greater latitude – say, encouraging donors “to be more effective when we try to help others” or to “maximize the good you want to see in the world” – then it becomes vapid. “I mean, who, precisely, doesn’t want to do good? Who can say no to identifying cost-effective charities? And with this general agreeableness comes a toothlessness, transforming effective altruism into merely a successful means by which to tithe secular rich people….”

Holden Karnofsky, a thought leader in the EA community, voiced mild concerns that utilitarianism could weaken the trustworthiness of effective altruists.

Even within the EA community there are thought leaders – Holden Karnofsky being one, Toby Ord another – who have reservations about ethical theories and analytical techniques that downplay the uncertainties and disputes around “the most good.” As Karnofsky explains: “EA is about maximizing how much good we do. What does that mean? None of us really knows. EA is about maximizing a property of the world that we’re conceptually confused about, can’t reliably define or measure, and have massive disagreements about even within EA. By default, …. I think it’s a bad idea to embrace the core ideas of EA without limits or reservations; we as EAs need to constantly inject pluralism and moderation.”

Toby Ord

As Ord adds: “[E]ven if you were dead certain … it would be a problem if you are trying to work together in a community with other people who also want to do good, but have different conceptions of what that means – it is more cooperative and more robust to not go all the way.”

Rejoinders to criticism #3

There are rejoinders to the criticisms of what the analytical methods of EA sideline, accommodate or downplay. With respect to their sidelining broader conditions like justice or freedom, as noted in part 3 EA supports such things indirectly where there are ties to measurable indicators: say, countering inequality by alleviating the effects of poverty; or promoting justice through criminal justice reform. That said, its methods steer clear of initiatives that wouldn’t improve well-being on terms and at levels greater than the alternatives at hand. This is a strength, not a weakness. Although not perfect, EA’s methods allow one to “sift through the detritus and decide what moral quandaries deserve our attention. Its answers won’t always be right, and they will always be contestable. But even asking the questions EA asks – How many people does this affect? Is it at least millions if not billions? Is this a life-or-death matter? A wealth or destitution matter? How far can a dollar actually go in solving this problem? – is to take many steps beyond where most of our moral discourse goes.” By promoting that discourse, EA provides a service to the philanthropic sector by “forcing us all to rethink what philanthropy should be.”

In an article in “Town & Country” magazine, Mary Childs writes that Effective Altruism picked up acolytes like Facebook billionaire Dustin Moskovitz, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, and Twitter’s Elon Musk. “To put it in pop culture terms: if Will Sharpe’s character on ‘The White Lotus’ existed in real life, he would be an effective altruist.”

For donors, by what standards do you gauge the extent to which your contribution improves the lives of others? Are these “presentable, articulable, reproducible”? For charitable organizations, what if anything makes you more deserving of donations than other organizations? How can that be demonstrated apart from storytelling, image promoting and heart-string tugging? To be sure, in recent years many in the charitable sector have pushed toward greater consistency in measuring impact. But this is usually only within a cause or at an organizational level. EA insists that “people think about how we decide on the causes themselves…. That type of thinking about charitable giving is becoming more public, and that’s something an effective altruist can take some credit for.” But taking credit doesn’t necessarily mean receiving thanks. Indeed, some of the criticism toward EA’s analytical methods may simply come from donors or entities put on the defensive: say, “donors that respond to causes that move them, regardless of their cost-effectiveness” or “activists committed to the cause of social justice” who feel offended by being asked or expected “to demonstrate that their work is effective.” Those on the defensive may also include the causes and organizations that EA leaders have used as examples of ineffectiveness or excess: cultural and arts organizations, Make-A-Wish Foundation, guide dogs, well-endowed universities or emergency relief for widely-reported disasters.

With respect to tolerating the value judgments that could skew decisions, EA is at least relatively transparent in what lies behind its decisions, thereby allowing others to question or challenge them and their associated risks. At the end of the day, however, judgements – ideally, defensible ones – need to be made. Sure enough, most effective altruists would agree there are instances where it’s worth risking failure and perhaps ending up with nothing. But in taking that position, they’re being consistent with recommendations made to the philanthropic sector as a whole by those who see greater risk-taking as necessary if the sector is to learn and make greater change, whether in Canada, the UK, the US or elsewhere. As for SBF’s bravado over extreme risk-taking, it would be wrong and unfair to attribute such recklessness to EA more broadly: “if SBF went to [William] MacAskill, or any of his largesse’s other beneficiaries, and asked, ‘Do you think I should make incredibly risky financial bets over and over again until I’m liquidated or become a trillionaire?,’ they would have said, ‘No, please do not bankrupt our institutions.’”

And finally, with respect to downplaying the uncertainties and debates around “the most good,” in fact EA recognizes and responds to such things. Admittedly, the focus remains on the needs of the beneficiaries and the cost effectiveness of alternative interventions to address them. But within those confines, the original EA organization Giving What We Can offers a range of funds that allows donors to support the high-impact causes and organizations that best correspond to their individual views on what constitutes the most good – whether these involve, for example, improving human well-being or animal welfare, alleviating climate change and its effects or averting catastrophic global risks in the future. And the EA foundation Open Philanthropy applies what it calls “worldview diversification”: where “worldview” refers to “a set of highly debatable (and perhaps impossible to evaluate) beliefs that favor a certain kind of giving” or cause area; and “diversification” means “putting significant resources behind each worldview that we find highly plausible”. Parentheses and italics are original. In other words, the foundation deliberately puts its eggs in multiple baskets – both to avoid rapidly diminishing returns from supporting only one or a few causes and to avoid estranging segments of the EA community that favour different worldviews.

And finally, with respect to downplaying the uncertainties and debates around “the most good,” in fact EA recognizes and responds to such things. Admittedly, the focus remains on the needs of the beneficiaries and the cost effectiveness of alternative interventions to address them. But within those confines, the original EA organization Giving What We Can offers a range of funds that allows donors to support the high-impact causes and organizations that best correspond to their individual views on what constitutes the most good – whether these involve, for example, improving human well-being or animal welfare, alleviating climate change and its effects or averting catastrophic global risks in the future. And the EA foundation Open Philanthropy applies what it calls “worldview diversification”: where “worldview” refers to “a set of highly debatable (and perhaps impossible to evaluate) beliefs that favor a certain kind of giving” or cause area; and “diversification” means “putting significant resources behind each worldview that we find highly plausible”. Parentheses and italics are original. In other words, the foundation deliberately puts its eggs in multiple baskets – both to avoid rapidly diminishing returns from supporting only one or a few causes and to avoid estranging segments of the EA community that favour different worldviews.

Criticism #3 as it applies to longtermism

Critics see extreme forms of methodological blindness affecting if not motivating EA’s pursuit of so-called longtermist causes and interventions – ones that, as described in part 2, seek to reduce the “existential risk” or “x-risk” posed by events or developments that “would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential.” Such threats include nuclear war and climate change, but now feature pandemics whether natural or bio-engineered as well as malicious artificial superintelligence (ASI) – a not-yet-realized state of AI that exceeds on all fronts the level of intelligence of which humans are capable.

For longtermist causes, the particular forms of methodological blindness emerge from the seemingly benign three-fold premise that: “Future people count. There could be a lot of them. And we can make their lives better.” First, consider the implications of “future people count.” Longtermists envisage people in the future as being both human and digital. In keeping with utilitarianism, they seek to increase the total well-being of future populations – a perspective known as the “total view”. Toward that end, they favour not simply protecting those populations but increasing them as long as the average well-being per person, whether human or digital, doesn’t fall so quickly as to reduce the total. For that reason, William MacAskill argues that “[i]f future civilization will be good enough, then we should not merely try to avoid near term extinction. We should also hope that future civilization will be big…. The practical upshot of this is a moral case for space settlement.” Thus, from a longtermist perspective, a population of 10 billion where each member flourishes with a high individual well-being of 100 is only half as well off as a population of 1000 billion where each member barely survives with a low individual well-being of 2. Heavily populated dystopias that are “good enough” are better than less populated utopias: a ranking known as the “repugnant conclusion” in population ethics, but accepted as a matter of logic by longtermists.

Nick Bostrom

Now consider “there could be a lot of them.” Nick Bostrom – introduced in part 2 as the founding and current Director of the Future of Humanity Institute – provides a range of estimates. For biological “neuronal wetware” humans, his projections for future life years range from 1016 if biological humans remain Earth-bound, up to 1034 if they colonize the “accessible universe”. Alternatively, if one assumes that such colonization takes place and that future minds can be “implemented in computational hardware”, then there could be at least 1052 additional life years that include digital ones where “human whole brain emulations … live rich and happy lives while interacting with one another in virtual environments”. Bostrom, as well as Hilary Greaves and MacAskill, assume that such digital minds will have “at least comparable moral status [as] we may have.”

Finally, consider “we can make their lives better” and the acceptable cost of doing this. Turning again to Bostrom and his projections, applying his lowest estimate of 1016 biological human life years left to come on Earth, he concludes that “the expected value of reducing existential risk by a mere one millionth of one percentage point is at least a hundred times the value of a million human lives” today. Alternatively, assigning “the more technologically comprehensive estimate of 1052 human brain-emulation subjective life-years” a mere 1% chance of being correct, he concludes that “the expected value of reducing existential risk by a mere one billionth of one billionth of one percentage point is worth a hundred billion times as much as a billion human lives” today. Italics are original.

Nick Bostrom, Elon Musk, Nate Soares, and Stuart Russell talking about AI and existential risk. Photo taken at the Effective Altruism Global conference, Mountain View, CA, in August 2015.

Thus by assuming future populations will be and should be massive, widening the notion of what constitutes a person in the future, claiming people who might exist in the future should be counted equally to people who definitely exist at present, and believing there’s no fundamental moral difference between saving actual people today and bringing new people into existence – longtermists argue that the loss of present lives is an acceptable cost of increasing by even a miniscule amount the probability of protecting future lives.

Greaves and MacAskill provide a specific example of this trade-off. Working with a projection of only 1014 future life years at stake and acknowledging that “[t]here is no hard quantitative evidence to guide cost-effectiveness estimates for AI safety”, they nevertheless propose that “$1 billion of carefully targeted spending [on ASI safety] would suffice to avoid catastrophic outcomes in (at the very least) 1% of the scenarios where they would otherwise occur…. That would mean that every $100 spent had, on average, an impact as valuable as saving one trillion lives … far more than the near-future benefits of bed net distribution” that would prevent deaths from malaria. Parentheses are original. As they see it, such calculations “make it better in expectation … to fund AI safety rather than developing world poverty reduction.” Or as put by Bostrom, because “increasing existential safety achieves expected good on a scale many orders of magnitude greater than that of alternative contributions, we would do well to focus on this most efficient philanthropy” rather than “fritter it away on a plethora of feel-good projects of suboptimal efficacy” such as providing bed nets.

Canadian philosopher Jan Narveson coined the phrase “total view”: “We are in favour of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people.”

Such implications – and the assumptions and methods used to support them – have attracted criticism from both within the EA community and outside it. For example, how and to what extent future people should count are topics of debate in population ethics. There’s no agreement on whether digital “brain emulations” would or could be morally comparable to human or other biological forms of sentient life – and hence whether their numbers or well-being should be included in population projections. And although longtermists endorse the “total view”, others don’t. Opposing it, for example, are those who endorse the principle of “neutrality” made popular by Canadian philosopher Jan Narveson (who also coined the phrase “total view”). According to that principle: “We are in favour of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people.” Neutrality can be linked with the principle of “procreation asymmetry” whereby there’s no moral imperative to bring into existence people with lives worth living (i.e., neutrality), but there’s moral imperative not to bring into existence people with lives not worth living. To be sure, these principles and their implications are themselves topics of debate. But together, they provide a credible philosophical rationale for concluding that “the longtermist’s mathematics rest on a mistake: extra lives don’t make the world a better place, all by themselves…. We should care about making the lives of those who will exist better, or about the fate of those who will be worse off, not about increasing the number of [sufficiently] good lives there will be.”

In a recent open letter, 11,258 scientists agreed that the world’s population be stabilized and that public policies “shift from GDP growth and the pursuit of affluence toward sustaining ecosystems and improving human well-being by prioritizing basic needs and reducing inequality.”

Such a non-longtermist conclusion supports those who tie human survival not to burgeoning populations somehow maintained by extraordinary levels of economic growth, but rather to making things work sustainably on Earth. According to the 2020 open letter signed by 11,258 scientists from 153 countries, this would require that the world’s population be “stabilized – and, ideally, gradually reduced” and that public policies “shift from GDP growth and the pursuit of affluence toward sustaining ecosystems and improving human well-being by prioritizing basic needs and reducing inequality.”

When it comes to the numbers of people that could exist in the future and our capacity to make their lives better, the tactic longtermists use to justify their position “is always the same: let’s run the numbers. And if there aren’t any numbers, let’s invent some.” Bostrom’s projections of many trillions over the next billion years rest on assumptions about space settlement, extra-terrestrial energy sources and digital storage capacity that he gathers from a range of literatures, including science fiction. These assumptions are questionable. Moreover, the time horizon is itself questionable – given the imminent threats posed by nuclear war and climate change. As put by one commentator, himself an effective altruist, “once you think like the world as we know it has a likely time horizon shorter than one thousand years, this notion of, well, what we will do in thirty thousand years … just doesn’t seem very likely. The chance of it is not zero. But the whole problem …starts looking … less like a probability that should actually influence … [our] decision making.”

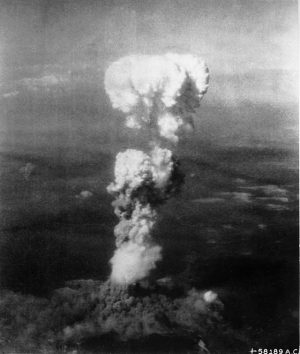

Radioactive smoke billows from the atomic cloud over Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. Part of the problem with longtermists is that they’re nearly clueless about the distant future. Many of the risks the world is worried about today, including nuclear war and climate change, emerged only in the last century.

The ways by which longtermists plan to make future lives better are themselves dubious. Part of the problem lies with our “cluelessness” both about what the distant future will be like and about what differences we could possibly make to that future by our actions today. “In truth, we cannot know what will happen 100 years into the future [let alone 30,000 years] and what would be the impact of any particular technology. Even if our actions will have drastic consequences for future generations, the dependence of the impact on our choices is likely to be chaotic and unpredictable. To put things in perspective, many of the risks we are worried about today, including nuclear war, climate change, and AI safety, only emerged in the last century or decades.”

Even when it comes to mitigating specific risks in the nearer future, it’s not clear what are the best actions in terms of their feasibility and effectiveness, let alone how the philanthropy of EA can uniquely advance those actions. Consider the threat of nuclear war. As reasoned by the commentator mentioned above: “I’m very keen on everyone doing more work in that area, but I don’t think the answers are very legible … [and] I don’t think effective altruism really has anything in particular to add to those debates.” With preventing malicious ASI, “I don’t think it’s going to work. I think the problem is if AI is powerful enough to destroy everything, it’s the least safe system you have to worry about. So you might succeed with AI alignment on say 97 percent of cases, … [b]ut if you failed on 3 percent of cases, that 3 percent of very evil, effective enough AIs can still reproduce and take things over….” Moreover, “artificial intelligence issues from a national perspective, not a global perspective. So I think if you could wave a magic wand and stop all the progress of artificial intelligence, …. you never have the magic wand at the global level.”

Maybe giving $1,000 to the Machine Intelligence Research Institute will reduce the probability of Artificial Intelligence killing us all by 0.00000000000000001. Or maybe it’ll make it cut the odds by only a fraction of that. Trying to reason with such small probabilities is nonsense.

Moreover, the willingness of longtermists to sacrifice large payoffs with probabilities arbitrarily close to one in order to pursue enormously larger payoffs with probabilities arbitrarily close to zero amounts to “fanaticism” – a willingness that could possibly be justified using expected value calculations for which the numbers were reliable. But the numbers aren’t: they give “a false sense of statistical precision by slapping probability values on beliefs. But those probability values are literally just made up. Maybe giving $1,000 to the Machine Intelligence Research Institute will reduce the probability of AI killing us all by 0.00000000000000001. Or maybe it’ll make it only cut the odds by 0.00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001. If the latter’s true, it’s not a smart donation; if you multiply the odds by 1052, you’ve saved an expected 0.0000000000001 lives, which is pretty miserable. But if the former’s true, it’s a brilliant donation, and you’ve saved an expected 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 lives.”

Trying to reason with such small probabilities is itself nonsensical. “Physicists know that there is no point in writing a measurement up to 3 significant digits if your measurement device has only one-digit accuracy,” writes Boaz Barak in a blog.

“Our ability to reason about events that are decades or more into the future is severely limited…. To the extent we can quantify existential risks in the far future, we can only say something like ‘extremely likely,’ ‘possible,’ or ‘can’t be ruled out.’ Assigning numbers to such qualitative assessments is an exercise in futility…. [I]f you are genuinely worried about long-term risk, I suggest you spend most of your time in the present. Try to think of short-term problems whose solutions can be verified, which might advance the long-term goal…. [T]o make actual progress on solving existential risk, the topic needs to move from philosophy books and blog discussions into empirical experiments and concrete measures.”

Rejoinders to criticism #3 as it applies to longtermism

To a large extent, the replies to such criticisms are calls not to toss out the baby with the more extreme implications of the longtermist bathwater. The premise that future people count rests on the basic message that “the long-term future matters more than we give currently give it credit,” whether in our philanthropy or public policy. That message isn’t unique to EA. It ties in with the Indigenous practice of seventh generation thinking whereby one assesses current decisions on how they will affect persons born seven generations from now. And it underlies the 2024 UN Summit of the Future.

Effective Altruism was a harbinger of protecting humanity from natural or bio-engineered pandemics or from malevolent Artificial Super Intelligence at a time when, apart from experts in public health and computer science, such things were seen primarily as the stuff of movies, such as “The Terminator.”

Moreover, one doesn’t need to “rely on the moral math [of longtermists] in order to think that human extinction is bad or that we are at a pivotal time in which technologies if left unregulated or unchanged could destroy us….” In terms of the technologies that pose such threats, EA was a harbinger of protecting humanity from natural or bio-engineered pandemics or from malevolent ASI at a time when, apart from experts in public health and computer science, such things were seen primarily as the stuff of movies (e.g.: 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968; The Andromeda Strain, 1971; Virus: The End, 1980; The Terminator, 1984) or fixations alluded to by critics as evidence of EA hand wringing. However, given the global experience of COVID-19 and the recent attentions and efforts in the US, at the United Nations and among the G7 about keeping AI safe, the concerns publicly raised by EA now seem more prescient than far-fetched.

In terms of deciding between the use of philanthropic resources to address tangible needs in the present as opposed to hypothesized needs in the future: such decisions and their dilemmas are not unique to EA. They operate, albeit with different intensities, across the philanthropic sector – going back to at least the 18th century as noted in part 1, and continuing now, for example, in debates around so-called strategic philanthropy. Indeed, versions of these debates exist within the EA community and among its longtermists.

Criticism 4: This methodology – bolstered by its ethical assumptions and claims of impartiality – cultivates hubris, condescension toward and dismissal of contending priorities or sources of information, and the impulse to define and control philanthropic interventions on one’s own terms.

“Any honest reckoning over effective altruism now will need to recognize that the movement has been overconfident. The right antidote to that is not more math or more fancy philosophy. It’s deeper intellectual humility.” Sigal Samuel, November 2022

“… there is still a strong element of elitist hubris, and technocratic fervor, in [EA’s] universalistic and cocksure pronouncements…. [T]hey could benefit from integrating much more systemic humility, uncertainty, and democratic participation into their models of the world.” Otto Lehto, January 2023

“This is a movement that encourages quant-focused intellectual snobbery and a distaste for people who are skeptical of suspending moral intuition and considerations of the real world…. This is a movement whose adherents … view rich people who individually donate money to the right portfolio of places as the saviors of the world. It’s almost like a professional-managerial class interpretation of Batman….” Zeeshan Aleem, December 2022

“Getting some of the world’s richest white guys to care about the global poor? Fantastic. Convincing those same guys that they know best how to care for all of humanity? Lord help us.” Annie Lowrey, November 2022

This second line of criticism against the analytical methods of EA focuses on the overconfidence they cultivate and how that can reinforce the methodological blindness outlined above. Such hubris takes on multiple but interconnected forms, all of which contribute to a strong if informal hierarchy within EA organizations and the community in general.

In Greek myth, Sisyphus was forced to roll a boulder endlessly up a hill because of his hubris.

The hubris can be intellectual. In part, this draws from the academic backgrounds of effective altruists of whom “11.8% have attended top 10 universities, 18.4% have attended top 25 ranked universities and 38% have attended top 100 ranked universities globally.” And in part, it stems from their “quantitative culture” and “[o]verly-numerical thinking [that] lends itself to homogeneity and hierarchy. This encourages undue deference and opaque/unaccountable power structures. EAs assume they are smarter/more rational than non-EAs, which allows … [them] to dismiss opposing views from outsiders even when they know far more than … [EAs] do. This generates more homogeneity, hierarchy, and insularity” from the broader academic and practitioner communities. Such insularity involves “prioritising non-peer-reviewed publications by prominent EAs with little to no relevant expertise…. [T]hese works commonly don’t engage with major areas of scholarship on the topics that they focus on, ignore work attempting to answer similar questions, nor consult with relevant experts, and in many instances use methods and/or come to conclusions that would be considered fringe within the relevant fields.”

As a consequence, EA risks becoming “a closed validation loop” that perpetuates an “EA orthodoxy” – one that privileges “utilitarianism, Rationalist-derived epistemics, liberal-technocratic philanthropy, Whig historiography, the ITN framework [see part 2], and the Techno-Utopian Approach to existential risk. Moreover, “contradicting orthodox positions outright gets … [one] labelled as a ‘non-value-aligned’ individual with ‘poor epistemics,’ so … [one needs] to pretend to be extremely deferential and/or stupid and ask questions in such a way that critiques are raised without actually being stated.”

Such intellectual hubris reinforces forms of donor hubris. The rhetoric used by EA leaders encourages those who support EA causes to think of themselves as “the hero, the savvy consumer, and the virtuous self-improver.” Such self-congratulatory images lead EA donors to respect and relate to each other, but not connect with or consult the objects of their philanthropy – particularly those affected by extreme poverty and the groups representing them. There’s little “effort to put the EA community in contact with activists, civil society groups, or NGOs based in poor countries,” thereby cutting off the community from the insights and resources of those with lived experience, and curtailing the types of consultation and power sharing with grantees that could foster local buy-in and increase the chances of change lasting beyond the immediate philanthropic interventions. By not engaging with and applying grassroots knowledge and forgoing the strategies taken, for example, by Solidaire, Thousand Currents or WIEGO – EA denies itself a possible means of doing more of “the most good.”

And finally, the hubris and hierarchy of EA takes on managerial and governance forms.

As a movement, EA “is deeply immature and myopic, … and … desperately needs to grow up. That means emulating the kinds of practices that more mature philanthropic institutions and movements have used for centuries, and becoming much more risk averse. EA needs much stronger guardrails to prevent another figure like Bankman-Fried from emerging….”

Indeed, the readiness of EA to align itself with SBF demonstrates the need for EA decision making to “be more decentralized,” and points to a “lack of effective governance” that currently looks “so top-down and so gullible.” As it stands, “[o]ne has to wonder why so many people missed the warning signs” – particularly when, as noted in part 3, those signs came as explicit warnings sent by multiple parties to MacAskill and other “[l]eaders of the Effective Altruism movement … beginning in 2018 that Sam Bankman-Fried was unethical, duplicitous, and negligent in his role as CEO….” The decisions made by EA leaders to affiliate so closely with SBF underscore the need for structural reforms within EA organizations along the lines drafted in early 2022 by Zoe Carla Cremer (see part 2) or drafted in early 2023 by the pseudonymous Concerned EAs.

In part, EA’s managerial immaturity can be attributed to its rapid transition in little over a decade from comprising a few student-founded and student-run organizations that relied on the camaraderie and confidence of a small homogeneous group to becoming a range of diverse and well-funded philanthropic organizations that still have many of the original students at the helm (see part 2). Given that transition, EA as a movement could be subject to the limiting or destructive effects of “founder’s syndrome” – a condition identified in both for-profit and nonprofit organizations exhibiting the following traits, aspects of which have been observed by members of the EA community.

Rejoinders to criticism #4

There are responses to the allegations concerning the intellectual, donor and governance hubris of EA. With respect to the intellectual forms – the ability of EA to attract smart and talented young people is a strength and to its credit, not a flaw or weakness. The criticisms of intellectual hubris could have equally been directed to activist organizations which “typically present themselves as more thorough-going, and more principled, champions of justice for the global poor than are their effective altruist opponents.” Intellectual insularity and organizational orthodoxies affect many philanthropic or mission-based organizations and movements, whether on terms that are religious, political, ethnic or methodological. Such organizations can’t be all things to all people: their stands or actions have to be consistent with their identity and purpose. That said, within each there’s usually room for intellectual diversity. At least that’s the case for EA: witness the debates on the EA online Forum. Besides, as noted by Karnofsky, “most EAs are reasonable, non-fanatical human beings, with a broad and mixed set of values like other human beings, who apply a broad sense of pluralism and moderation to much of what they do. My sense is that many EAs’ writings and statements are much more one-dimensional and “maximizy” than their actions.” Italics are original.

With respect to forms of donor hubris – EA is not alone in cultivating these. “Many argue that the traditional models and approaches we have for philanthropy are ones which put too much emphasis on the donor’s wishes and ability to choose, and give little or no recognition to the voices of recipients.” More pointedly, “a lot of charitable giving is about the hubris of the donor, rather than the needs of the recipient.” If anything, EA is an exception by focusing on the needs not of donors but of recipients and by addressing only those needs over which it has competence. For GiveWell, these relate to global health and nutrition that, once addressed, will “empower people to make locally-driven progress on other fronts.” GiveWell selects across alternative interventions by assigning quantitative “moral weights” to their good outcomes, where those weights reflect the priorities reported in a 2019 survey of persons living in extreme poverty in Kenya and Ghana. The weights, for example, place a higher value on saving lives as opposed to reducing poverty, and on averting deaths of children under five years old as opposed to older ones. Although seeking to act on the preferences of those with lived experience, GiveWell stops short of “letting locals drive philanthropic projects”, reasoning that local elites “who least need help will be best positioned to get involved with making the key decisions”.

With respect to forms of donor hubris – EA is not alone in cultivating these. “Many argue that the traditional models and approaches we have for philanthropy are ones which put too much emphasis on the donor’s wishes and ability to choose, and give little or no recognition to the voices of recipients.” More pointedly, “a lot of charitable giving is about the hubris of the donor, rather than the needs of the recipient.” If anything, EA is an exception by focusing on the needs not of donors but of recipients and by addressing only those needs over which it has competence. For GiveWell, these relate to global health and nutrition that, once addressed, will “empower people to make locally-driven progress on other fronts.” GiveWell selects across alternative interventions by assigning quantitative “moral weights” to their good outcomes, where those weights reflect the priorities reported in a 2019 survey of persons living in extreme poverty in Kenya and Ghana. The weights, for example, place a higher value on saving lives as opposed to reducing poverty, and on averting deaths of children under five years old as opposed to older ones. Although seeking to act on the preferences of those with lived experience, GiveWell stops short of “letting locals drive philanthropic projects”, reasoning that local elites “who least need help will be best positioned to get involved with making the key decisions”.

The need for reflection has been both identified by critics of EA and acknowledged by its leaders, such as William MacAskill, who said: “I had put my trust in Sam, and if he lied and misused customer funds he betrayed me, just as he betrayed his customers, his employees, his investors, & the communities he was a part of. For years, the EA community has emphasised the importance of integrity, honesty, and the respect of common-sense moral constraints.”

Finally, in terms of managerial hubris – the broad-brush criticisms, whether valid or not, are cast as if EA comprises one organization with a single founder, organizational chart or set of governance procedures. It doesn’t. Instead it comprises multiple organizations – those under the auspices of Effective Ventures (e.g., the Centre for Effective Altruism, 80,000 Hours, and Giving What We Can as introduced in part 2, in addition to others such as the Centre for Governance of AI and the Forethought Foundation for Global Priorities Research), as well as a range of research organizations (e.g., the Future of Humanity Institute, Machine Intelligence Research Institute, Global Priorities Institute, GiveWell) and foundations (e.g., Open Philanthropy). Sure enough, certain individuals have longstanding and multiple ties with these organizations, and presumably have informal influence across several. Ord, for example, co-founded Giving What We Can in 2009, and is a research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute, and a trustee of both 80,000 Hours and the Centre for Effective Altruism. MacAskill – described as “a co-founder the effective altruism movement,” as well as its “prophet” – co-founded Giving What We Can in 2009, 80,000 Hours in 2011, the Centre for Effective Altruism in 2012, as well as the Global Priorities Institute and the Forethought Foundation in 2017 of which he is the Director. But on the basis of these personal ties, it would be wrong to conclude that all of these diverse organizations exhibit the same management styles or governance structures, let alone that those styles and structures are somehow dysfunctional. Moreover, it would be wrong to infer such dysfunctionality from the decisions of MacAskill and others to affiliate with or tolerate SBF. As noted in part 3, his alleged malfeasance went unrecognized by many investors and associates. And any rumours of his bad behaviour were not evidence of criminal behaviour.

Criticism #4 as it applies to longtermism

Critics see acute forms of hubris in EA’s formulation and defence of longtermist causes. They attribute the intellectual forms to the prevalence of academic philosophers among EA thought leaders (e.g., Bostrom, Greaves, MacAskill, Ord, and Singer). Philosophy is known for its “tendency to slip from sense into seeming absurdity.” No doubt “[t]hese are all smart people, but they are philosophers, which means their entire job is to test out theories and frameworks for understanding the world, and try to sort through what those theories and frameworks imply. There are professional incentives to defend surprising or counterintuitive positions, to poke at widely held pieties and components of ‘common sense morality,’ and to develop thought experiments that are memorable and powerful (and because of that, pretty weird).” Parentheses are original. In other words, “[t]he philosophy-based contrarian culture [of EA] means participants are incentivized to produce [what at least some would consider] ‘fucking insane and bad’ ideas….” The types of reasoning and rhetoric that set out to be provocative may be the stuff of creative seminar discussions or fun dorm-room debates. But in their raw form, they hold little credibility beyond the inner clique of academics and the autodidacts who want to be among them.

This intellectual hubris shaping and shaped by longtermism leads to multiple problems. First, it leads to inconsistencies if not misrepresentations in communication. In packaging their thinking and conclusions for a general audience, thought leaders deliberately tone down the “more fanatical versions” in order to widen the “appeal and credibility” of longtermism. Second, intellectual insularity becomes “especially egregious” when applied to a “domain of high complexity and deep uncertainty, dealing with poorly-defined low-probability high-impact phenomena, sometimes covering extremely long timescales, with a huge amount of disagreement among both experts and stakeholders along theoretical, empirical, and normative lines. Ask any risk analyst, disaster researcher, foresight practitioner, or policy strategist: this is … where you maintain epistemic humility and cover all your bases” by consulting and learning from research areas that EA typically ignores (e.g., studies in “Vulnerability and Resilience, Complex Adaptive Systems, Futures and Foresight, Decision-Making under Deep Uncertainty/Robust Decision-Making, Psychology and Neuroscience, Science and Technology Studies, and the Humanities and Social Sciences in general”).

Third, the “philosophers’ increasing attempts to apply these kinds of thought experiments to real life – aided and abetted by the sudden burst of billions into EA, due in large part to figures like Bankman-Fried – has eroded the boundary between this kind of philosophizing and real-world decision-making…. EA made the mistake of trying to turn philosophers into the actual legislators of the future.” Rephrasing this problem more pointedly: “[t]ying the study of a topic that fundamentally affects the whole of humanity to a niche belief system championed mainly by an unrepresentative, powerful minority of the world is undemocratic and philosophically tenuous.” Or more mildly: “it does seem convenient that a group of moral philosophers and computer scientists happened to conclude that the people most likely to safeguard humanity’s future are moral philosophers and computer scientists.” Perhaps convenient for them but fool-hardy for us if we rely on those philosophers and computer scientists to sort out the ways to safeguard the future in accord with humanity’s preferences, let alone frame the national policies or international agreements purportedly capable of doing this.

With respect to donor hubris, critics see longtermism as catering to this at the expense of methodological rigour. “As much as the effective altruist community prides itself on evidence, reason and morality, there’s more than a whiff of selective rigor here. The turn to longtermism appears to be a projection of a hubris common to those in tech and finance, based on an unwarranted confidence in its adherents’ ability to predict the future and shape it to their liking.” Hence, it’s not a coincidence that “the areas EA focuses on most intensely (the long-term future and existential risk, and especially AI risk within that) align remarkably well with the sorts of things tech billionaires are most concerned about: longtermism is the closest thing to ‘doing sci-fi in real life’, existential catastrophes are one of the few ways in which wealthy people could come to harm, and AI is the threat most interesting to people who made their fortunes in computing.” Parentheses are original.

Rejoinders to criticism #4 as it applies to longtermism

William MacAskill

Not surprisingly, there are replies to the allegations of intellectual and donor hubris tied to longtermism. In terms of the intellectual forms, first note that “[i]t is appropriate for philosophers to speculate on hypothetical scenarios centuries into the future and wonder whether actions we take today could influence them.” Second, “even longtermists don’t wake up every morning thinking about how to reduce the chance that something terrible happens in the year 1,000,000 AD by 0.001%. Instead, many longtermists care about particular risks because they believe these risks are likely in the near-term future….” Indeed, MacAskill makes this point in arguing that the costs of protecting the future are “very small, or even nonexistent” since most of the things – disaster preparedness, climate-change mitigation, scientific research – we want to do for ourselves for the near future. Nevertheless, “[t]his does not mean that thinking and preparing for longer-term risks is pointless. Maintaining seed banks, monitoring asteroids, researching pathogens, designing vaccine platforms, and working toward nuclear disarmament, are all essential activities that society should take. Whenever a new technology emerges, artificial intelligence included, it is crucial to consider how it can be misused or lead to unintended consequences.”

Third, as noted above, one should not judge longtermism by the extreme positions found within the rhetoric or reasoning of a “philosophy-based contrarian culture.” Indeed, so called “weak longtermism” – the position that the “long-term future matters more than we’re currently giving it credit for, and we should do more to help it”, climate change being a case in point – may indeed be its strongest, most persuasive and powerful form.

And fourth, by focusing on the bravado, some criticisms of longtermism verge on ad hominem attacks, and most overlook signs of humility. Consider, for example, MacAskill admitting that he doesn’t know the answer to the question “How much should we in the present be willing to sacrifice for future generations?” Or his acknowledging that “[m]y No. 1 worry is: what if we’re focussed on entirely the wrong things? What if we’re just wrong? What if A.I. is just a distraction? … It’s very, very easy to be totally mistaken.”

With respect to donor hubris, billionaires from Silicon Valley – regardless of whether or where they practice philanthropy – aren’t known for their modesty. Moreover, longtermist forms of donor hubris don’t altogether dominate EA. Recent estimates of the funding going to “Global Health” are twice those going to “Biosecurity” and “Potential Risks of AI” combined. What is more, “[m]any ‘longtermists’ have given generously to improve people’s lives worldwide, particularly in developing countries. For example, none of the top charities of GiveWell (an organization … in which many prominent longtermists are members) focus on hypothetical future risks. Instead, they all deal with current pressing issues, including malaria, childhood vaccinations, and extreme poverty. Overall, the effective altruism movement has done much to benefit currently living people.” And it still does.

What can we take from the downfall of Samuel Bankman-Fried with regard to the analytical methods of Effective Altruism?

SBF expressed great confidence in financing selective interventions to reduce the existential risk posed by pandemics and ASI, and in ranking them solely on the basis of expected value calculations, regardless of the odds. And although he supported political campaigns, he did so to promote not institutional change but rather EA and an unregulated crypto industry. Are he and the adulation he received the exceptions that prove the general rule that the analytical methods of EA are sound and unencumbered by the quantification they require, the hubris they encourage or the deflection from systemic conditions they justify? Or is he the example that demonstrates those methods are defective on those terms? Or is he neither?

Regardless of how one answers such questions, the bankruptcy of FTX International and the criminal charges brought against SBF in late 2022 enlivened the existing criticisms of EA’s analytical methods. Many of us affiliated with the philanthropic sector might see the criticisms as being relevant only to EA and its approach to philanthropy and having little to do with the sector as a whole. But is that the case? Here I select six areas in which the criticisms might have implications beyond EA.

1. What data would allow the sector, your organization or you as a donor to become better at recognizing societal needs and addressing them? Do we have the skills – or even the willingness to acquire the skills – needed to interpret and apply those data?

EA has been faulted for its “quantitative culture” and “overly-numerical thinking”. But could such a culture and thinking empower the philanthropic and charitable sector by strengthening its abilities to recognize societal needs and address them more effectively? Sector leaders in Canada think so – placing among their top priorities the need to acquire more data for and about the sector, and calling for the sector to “grow up” in terms of investing in the technology, the talent, and the delivery and evaluative processes that would allow it to learn from and apply those data. Rather than disparage EA’s quantitative methods and talents, could we learn from and make use of them?

2. Can catering to the needs of donors – or, indeed, your own needs as a donor – impede the effectiveness of philanthropy? If so, then how can this be avoided or overcome?

Understandably, donors need to recognize their own priorities in the mission and accomplishments of the organizations to which they give. And undoubtedly, EA’s track record in managing donor relations has been far from perfect. However, its starting point has been the needs of beneficiaries: first identifying the particular causes and interventions that would do the most good for them with a given amount of resources, and then recruiting the donors who wish to support this venture. As noted in part 2, those causes and interventions are ranked according to their cost effectiveness – not their donor appeal per se. Many of us work in or with charitable organizations with given missions and sets of beneficiaries. But are their ways either to manoeuvre within a mission or amend it that would increase the cost effectiveness of the work you do? If not, are their other organizations with missions and beneficiaries that would better match your priorities?

3. What’s the risk tolerance of your organization or for your charitable giving? Do you have the resources and opportunities to take greater risks – ones that could open up ways to make greater change or at least learn how to do so? If not, then what other things could enable you to make your philanthropy more effective?

As noted above, the philanthropic and charitable sector has been faulted for being too staid and risk adverse, preferring safe but modest ventures that limit what the sector can achieve. How can we learn from the EA community about tolerating greater risk without falling into the recklessness evinced by SBF? What opportunities would open up if we moved in that direction? What would be the personal or organizational costs of doing so? How could those costs be overcome?

4. Are all charitable purposes equal in their potential to create social benefit where it’s most needed? If so, why is that the case? If not, then what changes could allow the sector and the donations it receives to become more beneficial?

As noted, EA uses quantitative methods to rank the cost effectiveness of not only alternative interventions within a cause, but also the causes themselves, regardless of where or when the beneficiaries are located – relegating those that are less cost effective to the category of luxury spending. A given donor might prefer giving to an opera company over a local food bank, a local food bank over the Ice Bucket Challenge, and the Ice Bucket Challenge over a fund encouraging childhood vaccination against malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. In Canada, only the latter doesn’t constitute charitable giving because the organization Malaria Consortium isn’t registered here. According to GiveWell, however, only the latter doesn’t constitute luxury spending based on cost effectiveness. Some jurisdictions provide higher or lower tax credits or deductions according to those causes believed to generate higher or lower social benefit. Some, although sharing Canada’s common law tradition (e.g., Australia, India, Singapore), deny any tax incentives for giving to places of worship. What’s your take on this?

5. How can young but maturing charitable or nonprofit organizations remain inspired by the vision and dedication of their founders but nevertheless be able to adapt, plan and decide in part by drawing upon the expertise and input of others whose views differ from or challenge those of the founders?

To endure and adapt, organizations need to become more than extensions of their founders’ original vision and initiative. Such growth is not an easy or straightforward process either for the founders whose identity may tied to the work of the organizations, or for the organizations and their stakeholders that have become accustomed to simply trusting and following the personal decisions or priorities of the founders. Whether or not EA organizations are subject to so-called “founder’s syndrome” – there is still a value in those organizations and others establishing decision-making procedures that are transparent and consultative, and avoiding founder or funder burnout. Have the organizations you have worked in or with been able to mature on those terms? If so, has anything been lost in the process? If not, what or who is impeding this?

6. Do the needs of future generations explicitly and regularly fit into the mission and work of your organization or the priorities that guide the directions and amounts of your charitable giving? If not, then how do you justify not taking those needs into account – beyond claiming there are already too many needs in the present day?

How should the philanthropic sector divide its resources across the needs of current and future generations? How does or should this differ from the responsibilities of government?

Conclusion

Samuel Bankman-Fried

The downfall of Samuel Bankman-Fried has renewed calls for Effective Altruism to reconsider the analytical methods it uses to rank philanthropic causes and interventions. To my mind, the criticisms around quantification, hubris and systemic conditions – and their rejoinders – raise issues and questions relevant to the philanthropic sector as a whole.

In part 4 of this series, I’ve summarized those criticisms and their rejoinders and have posed several related questions for those of us working in or with the sector. My intent here, as with part 3 and the forthcoming part 5, isn’t to fault or exonerate EA. Instead, it’s to point out that the issues on which EA is or should be reflecting – particularly after the downfall of SBF – are ones that could help more of us across the sector to reconsider and perhaps revise our own analytical methods and skills in our shared hope of being better able to benefit current and future generations.

Banner photo is courtesy of Erik Mclean.

Monday, September 11, 2023 in EA, For homepage, News & Events

Share: Twitter, Facebook