The “Canadian” Wildfires of 2023

On June 5, 2023, as over 200 wildfires raged across the country, the federal government through a whole-of-cabinet approach issued a lengthy official update informing Canadians that “current June projections indicate the potential for continued higher-than-normal fire activity across most of the country throughout the 2023 wildland fire season.” With the wildfire season typically running May through October, the hottest months of this season still lay ahead.

The research scope of the Disaster Lab examines how disasters, migrations, and citizenship have been historically shaped by government responses. More often than not, and certainly in the here and now of 2023, the impact of climate disasters on human displacement will only worsen.

The overt focus this past week on the “post-apocalyptic” imagery coming out of urban centres such as Toronto and New York feels like the manifestation of decades of First World disassociation in being only able to comprehend ecological ruin to popular movies steeped in sepia filters. These comparisons are also deeply rooted in settler colonial logics that marginalize how climate disasters negatively impact Indigenous communities first.

Wildfire Impacts on Indigenous Peoples

For example, in 1991, close to 7000 people were evacuated from the First Nations and Innu communities of Montagnais Reserve of Betsiamites and the communities of Ragueneau and Baie Comeau in Northern Quebec. Of the 113 nation-wide wildfire disasters recorded by the Canadian Disaster Database between 1911 to present day, First Nations communities are disproportionately impacted.

Presently, one of the hardest hit communities are the Algonquins of Barriere Lake whose territories are located along the present-day Ontario-Quebec border. Surrounded by fires from the East, North, and West, at least 500 people have been evacuated to Gatineau and Maniwaki ( for CBC Indigenous & for CBC Ottawa). Many are unsure if the cabins they live in year-round will survive through the season. As Deer reports, the 750 members of Lac Simon Anishnabe Nation was pre-emptively evacuated to Val d’Or (and have since returned home) while Kitigan Zibi, located two hours north of Ottawa and home to over 1500, have remained on high alert for possible evacuation.

Meanwhile, Ontario’s Premier Doug Ford refused to acknowledge there is even a connection between the intensity of this year’s fires with climate change because wildfires “happen every single year.” Within the last one hundred years, there has only been a handful of times when more than 100 forest fires have burned simultaneously in Ontario and Quebec. One instance was in the summer of 1955, when at the height of the wildfire season in July and August, more than 100 forest fires burned across the region for more than four weeks. 150 forest fires were recorded on August 5 alone, costing the federal government an estimated $24,402,775 (presumably in 1955 figures). While wildfires are naturally occurring phenomenons, their intensity has significantly risen from drier hotter weather conditions since the 1980s, which is also the earliest data points for the Canadian National Fire Database maintained by Natural Resources Canada.

Wildfire Comparison Between 2011 and 2023

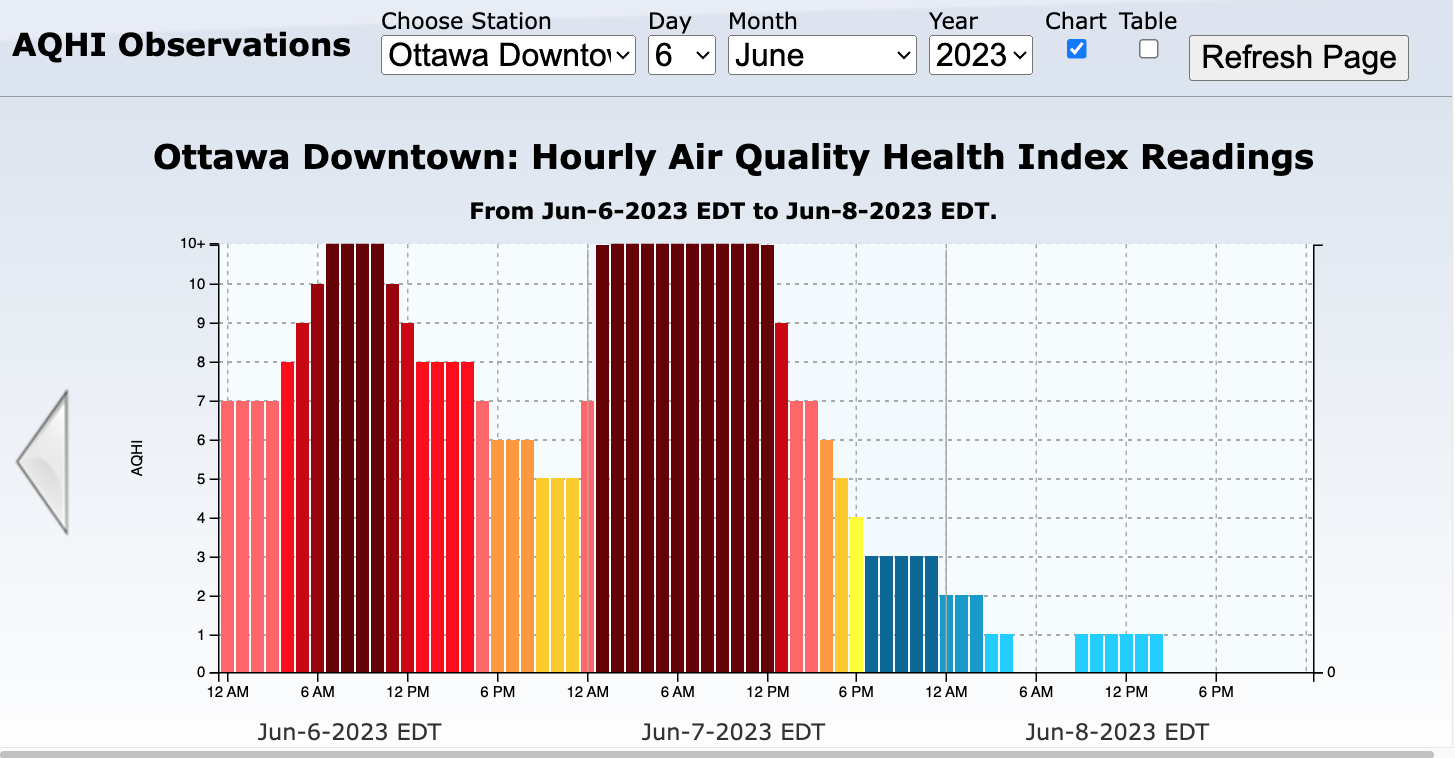

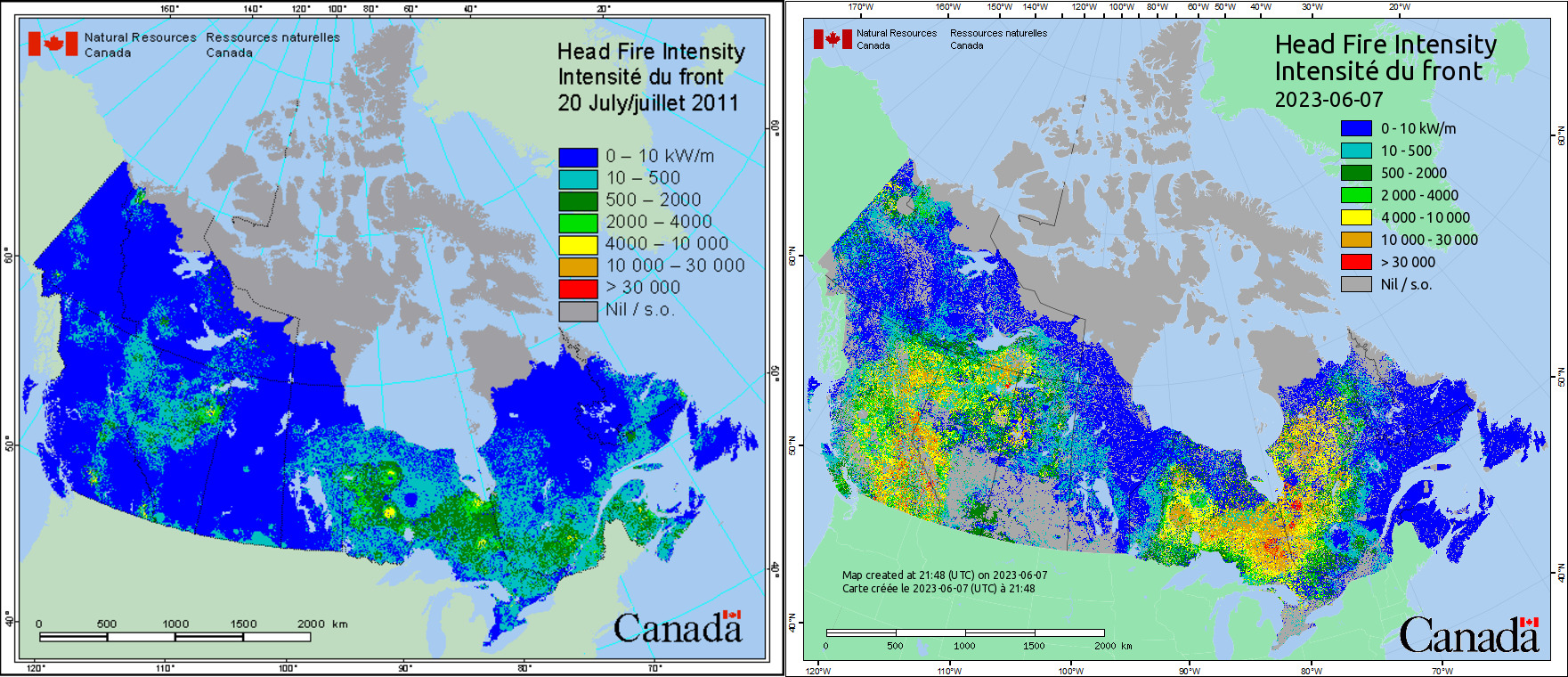

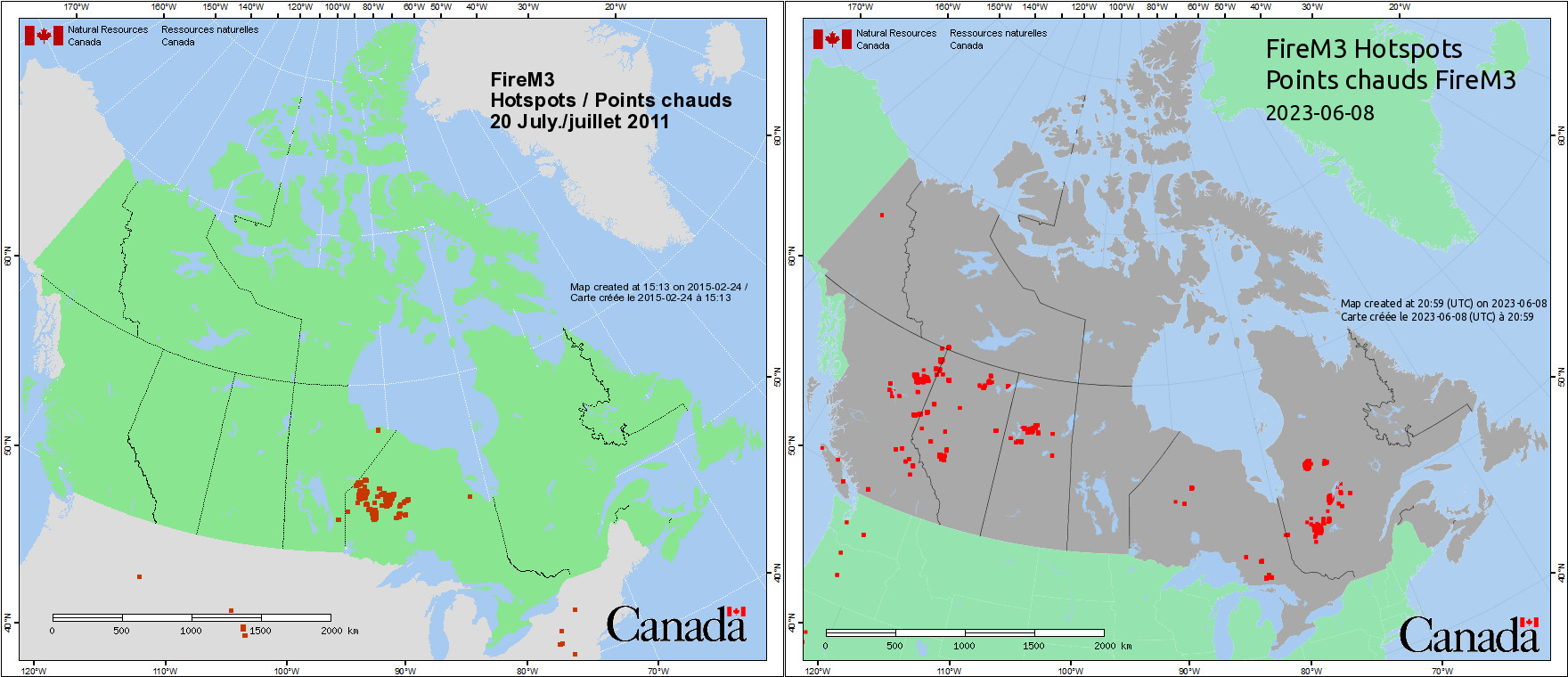

As seen above and below, users can generate their own maps of fire behaviour on the CNFDB site, but only between 2000 to present-day. With this date restriction applied, I generated a comparison between the hundreds of wildfires burning this week (June 7, 2023) and when 112 fires were simultaneously burning across Ontario (July 20, 2011). According to the CDD, the July 2011 wildfires caused the largest evacuation of people in central Canada between the year 2000 to present day when over 3300 people (from over ten different First Nations communities) needed to be evacuated.

Blame Game

Counting only for the month July of 2018, 549 wildfires were recorded across Ontario. Despite the staggering total figure of “1,325 fires that burned over 275,000 ha of land” that is double the 10-year average in 2018, and the already 33,000 ha burned in the first week of June of 2023, the Premier recently dismissed his critics who asked him to confirm the existence of climate change as “politicizing the wildfires.” Climate change is a political issue because every government has policies and budgets dedicated to its prevention and relief. However, to continue approaching climate change as a partisan issue and accepting this intensity of wildfires as perfectly natural and a “new normal” is a form of harm.

South of the border, Americans have unhelpfully reframed the culprit of the hazardous air quality to be “Canadian wildfires.” Holding onto the last shred of American exceptionalism, where the wealthiest country in the world since WWII can still reap all the benefits of plundering nature, but be spared the fault and consequences, the blame for over a century of over consumption has been squarely blamed on a foreign nation rather than the global issue of climate change.

As a cheeky reference to Comedy Central’s South Park and a summation of how US media has generally framed these wildfires (and climate change in general) as foreign problems, the lack of solemnity to climate disasters remains the greatest danger to us all.

– Amy Fung