RENDER Blog 11 – Reference Reformation/Representation

Reference Reformation/Representation: A Grad Student Reflects on the Archive of Canadian Women Artists

By Diana Hiebert

One of the reasons I am drawn to the field of art history is its connection to story. As researchers in the context of Western art history, we are often self-conscious about our storytelling framework, ominously dubbed ‘The Canon of Art History.’ Common criticisms are that it is too male, too white, and too western. We are eager to make amends for the transgression of previous generations who passed over minority artwork. Although the very concept of a singular canon is controversial, it is, what I believe to be, an essential construct necessary to apprehending alternate views of seeing the world. A framework, however controversial and misguided, can function as a kind of narration from which to make sense of our place in a pluralistic society.

Whether implicit or explicit, all stories have a narrator. In the same way that the ‘canon’ has to be widened, we must also turn our attention to other methods of storytelling. In contrast to omniscient voice when speaking about artwork, feminist artists of the 1970s chose to embrace a personal voice in reaction to the authoritative meta-narrative.[i] In response to this changing mode of expression, art history scholars “have explored the pragmatic or ‘performative’ dimension” of gender theory.[ii] Often, this is made manifest in the theorist’s uncovering of personal biases, an act that allows readers to more easily detect a framework from which to interject their own opinions. [iii]

Feminisms provide other narratives to study and spaces to research, ways to look at the omitted and neglected work of artists who were women, as well as to reconsider the masculine canon, to name the ways in which gender is enacted in the practices of art-making and its reception.[iv]

One such scholar interested in widening the ‘canon’ is former Carleton professor Natalie Luckyj (1945-2002) who is considered, in the words of Dr. Angela Carr, to be “one of the pioneers in the field of Canadian women artists.”[v] From 1986 until her untimely death in 2002, Luckyj compiled the Archive of Canadian Women Artists (ACWA), a reference collection of books, journals, slides, and ephemera. Nancy Duff, supervisor of Carleton’s Audio-Visual Resource Centre (AVRC), responsible for bringing the collection to the AVRC in 2004, sees Luckyj’s archive as a “quest to rescue from oblivion and champion the stories of women artists in Canada.”[vi] According to Dr. Brian Foss, director of the School for Studies in Art and Culture, Luckyj created the ACWA “during a time when there was less professional activity than there was in subsequent years in amassing documentation about women artists”[vii]

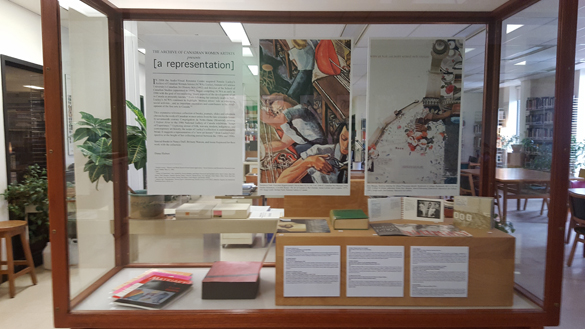

Last term, I was fortunate to work with the ACWA located in Carleton’s AVRC. One of my main tasks was to organize a display that highlights major plot points (the lives and work of Canadian women artists) in Luckyj’s collection. This is quite a task, given that in 1986 she bracketed her particular ‘canon’ between the late seventeenth- to early eighteenth-century painting L’Enfant Jésus by an unknown artist (although traditionally associated with Sister Marie Barbier) and the 1986 group exhibition Songs of Experience, curated by Jessica Bradley and Diana Nemiroff.[viii] The scope of the collection certainly attests to Luckyj’s broad interests that encompass contemporary art, indigenous art, historical folk art and Canadian architectural history.

Throughout the project, I considered the question: What is the merit of maintaining an archive like ACWA for its historical perspective on women artists in relation to the Canadian identity versus building on the archive as a contemporary resource which responds more fully to current discussions of gender in the Canadian context? Although the exhibition currently on display in the AVRC showcase is reflexive of the former option, it is a question for continual consideration.

Displayed is a sampling from the archive highlighting the work of various women artists who were pioneers in their own right. They include a literary account of 1830s life in Upper Canada by Catherine Parr Traill; an exhibition catalogue chronicling the visual practices of Montreal women artists of the 1920s and 1930s; a collection of feminist art journals published in the 1990s; and a multimedia exhibition catalogue designed by intermedia artist Joey Morgan. Each of these works respectively challenge the patriarchal boundaries within Canadian art history, effectively contributing to Luckyj’s “new art history” narrative.[ix]

Editor’s Note: Be sure to visit the Audio-Visual Resource Centre on the fourth floor of the St. Patrick’s Building at Carleton to see the exhibition highlighting Luckyj’s essential archive of Canadian women artists. To learn more about the ACWA, contact Nancy Duff, Supervisor, Audio-Visual Resource Centre (613-520-2600 x 2348 or nancy.duff@carleton.ca).

About the Author: Diana Hiebert is a first year graduate Art History student with a concentration in Art Exhibition and Curatorial Practices. The focus of Diana’s research at Carleton will be to map artistic and aesthetic Mennonite histories in Canada and to explore questions of Mennonite identity within the contemporary art context. You can read more about Diana here.

==========================================

[i] Laura Meyer, “Power and Pleasure: Feminist Art Practice and Theory in the United States and Britain,” in Amelia Jones, ed., A Companion to Contemporary Art Since 1945 (Carlton: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 318.

[ii] Whitney Davis, “Gender,” Critical Terms for Art History, edited by Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, Second edition (Chicago: Chicago UP, 2003), 343.

[iii] See Steven Z. Levine, “Manet’s Man Meets the Gleam of Her Gaze: a Psychoanalytic Novel,” in Bradford Collins ed. 12 Views of Manet’s Bar (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1996), 250-77.

[iv] Griselda Pollock, “The “View from Elsewhere”: Extracts from a Semi-public Correspondence about the Visibility of Desire,” in Bradford Collins ed. 12 Views of Manet’s Bar (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1996), 279.

[v] Angela Carr, email interview, 21 November 2016.

[vi] Nancy Duff, email interview, 13 December 2016.

[vii] Brian Foss, email interview, 17 November 2016.

[viii] This exhibition highlighted works by several artists, including women artists like Jamelie Hassan, Nancy Johnson, Wanda Koop, Mary Scott, Jana Sterbak, Joanne Tod, Renée Van Halm, and Carol Waino.

[ix] Angela Carr, “Introduction,” Raven Papers: Remembering Natalie Luckyj (1954-2002) edited by Angela Carr (Manotick: Penumbra Press, 2010), xii.