Friends of Art History Visual Culture Series 2012/13

Friday, April 19, 2013, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Building.

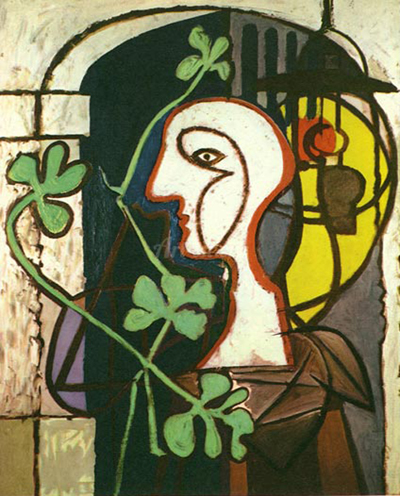

“Picasso’s Plants”

by Alma Mikulinsky, PhD, Research Scholar at the Society of Scholars in the Humanities at the University of Hong Kong

“Ce n’est pas d’après nature que je travaille, mais devant la nature, avec elle (I do not work “after nature,” but before nature, with her.)” Pablo Picasso in conversation, June 15th 1932

In June 1932, the first comprehensive Pablo Picasso retrospective ever to be mounted opened at the lavish Georges Petit Galleries in Paris. The show was arranged by the artist himself and was Picasso’s largest exhibition to date consisting of 225 paintings, seven sculptures, six illustrated books and, strangely, one lowly house plant of the philodendron variety.

Whereas art historians underscore a single curatorial feature of the retrospective – Picasso’s choice of non-chronological hanging – I propose to focus on the plant as a part of the exhibition’s curatorial program. By analyzing recently discovered installation photographs of the retrospective, I will trace the repeated appearances of this particular philodendron throughout the show in real, painted, and sculpted form. This allegedly minor detail then transforms into an important motif which provides a more nuanced understanding of Picasso’s hanging strategies.

Flora is also at the heart of André Breton’s 1933 “Picasso in his Element,” a text devoted to the artist’s sculptural oeuvre that also describes the Petit show. The writer highlights the introduction of real plants, leaves, roots, feathers, butterflies, and flies in the artist’s recent work and interprets their presence as an attempt to blur what is usually conceived as the unshakable boundaries between nature and culture, the animate and the inanimate. This new role assigned to art reveals some of our discipline’s biases and blind spots while also opens up a possibility of going beyond art history’s tendency to see nature only if represented through artistic means.

===========================================

PAST TALKS

===========================================

Friday, March 22, 2013, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Building.

“Rushnyky in the Built Environment: A New Interpretation of an Old Art Form”

by S. Holyck Hunchuck, Independent Scholar

A rushnyk (pl. rushnky) is the Ukrainian term for the ornamented cloths used to mark all points of social transition in life and death as well all points of transition in space. Rushnyky are ancient in origin but their use continues to the present day. This paper traces the forms and origins of traditional Ukrainian rushnyky and places them in their context of the history of European art and architecture, with particular reference to Slavic cultures. It will also examine how these textiles have influenced forms of building in Canada. It concludes with a proposal that a study of the rushnyk in its various manifestations lends itself to a deeper understanding of both modern architectural theory, with reference to Gottfried Semper and Adolf Loos, and to recent practice, with reference to the architecture of the Pavilions of Poland and the Russian Federation at Shanghai, 2010, and to the artwork of Christo and Andy Warhol.

===========================================

Friday, February 1, 2013, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Building.

“Barlow and the Spectacle of Nature”

by Dr. Nathan Flis, Postdoctoral Fellow, School for Studies in Art and Culture.

Based on his recently completed doctoral work at the University of Oxford, Nathan Flis (SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in Art History at Carleton) will discuss the art of English artist, Francis Barlow(c.1626-1704), famous in his own time as a painter of birds and beasts, and also as a book illustrator and political satirist. Barlow was a keen observer of nature and society alike, and his pictures present an opportunity to learn about seventeenth-century English society’s vision of, and relationship with, the natural world. Drawing from a selection of works, it is argued that we can better understand Barlow’s large and complex oeuvre by applying the theme of theatrum mundi –the world stage, or theatre of the world. As William Hogarth would later do in his pictures of the men and women of London, Barlow came to employ birds and animals as ‘actors’ in allegorical paintings and in designs for broadsides and book illustration. The perceived drama of the natural world and that of society was thus re-imagined and re-performed according to Barlow’s vision. In this regard, the artist himself might be likened to a showman or trickster, devising a separation between reality and fantasy: re-casting what he had studied in the natural world in the mould of a fable, or representing contemporary social and spiritual anxieties of the age in the guise of the contents of the theatre of nature.

===========================================

Friday, January 18, 2013, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Building.

“Broadcasting Modern(istic) Architecture in Canada”

by Michael Windover, Assistant Professor, Art History.

Radio and architecture intersected to create complex social spaces of political import in the 1930s and 1940s. This talk will explore some of the material aspects of radio, as it became a common sight in Canadian households at this time, focusing in particular on how the new medium (and its institutions) was framed as modern. 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Building.

===========================================

Friday, November 16, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Bldg

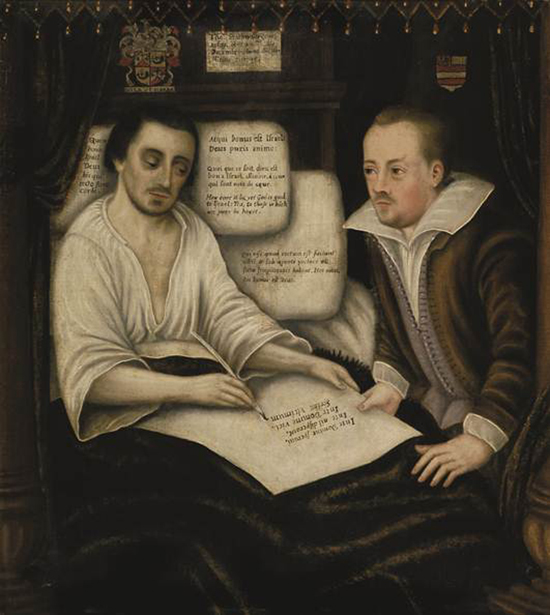

“Portraiture and Memory in Post-Reformation England”

Dr. Robert Tittler, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Concordia University, Adjunct Professor, Carleton University

Drawing from his most recent publication, Portraits, Painters and Publics in Provincial England, 1540-1640 (Oxford University Press, 2012), Robert Tittler will explore the connections between portraiture and the creation of memory in this tumultuous era.

Image Caption: English School. (17th century).Thomas Braithwaite of Ambleside (d.1607) making his Will. 1607, oil on board. Courtesy Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, Cumbria, UK.

===========================================

Friday, September 28, 12:00 noon, 412 St. Patrick’s Bldg

David Richler, PhD Student, ICSLAC, Carleton University

“On the Paratextual Significance of Titles”

To give a text a title, or a descriptive caption, is to add meaning and value to it. It names and therefore describes the text, and in doing so — borrowing Judith Halberstam’s apt description — it “confers, rather than reflects meaning” (1998). As the most immediate paratextual frames through which most viewers will come into contact with texts (artworks, books, films, television programs, etc…), I argue that titles, perhaps even more so than other paratexts, heavily frame the meaning-making process. This grants them a particularly vital responsibility. It is surprising, then, that so little attention has been paid to the meaningful role they seem to play. This is especially odd given the fact that films, and to an even greater extent the paratexts which surround them, significantly blur the boundaries between verbal and visual media, generating a multiplicity of meanings through their interactions.

Using examples from across the spectrum of film history, my presentation will consider these issues by looking at various kinds of screen titles, including main titles, subtitles, silent film inter-titles, and opening title sequences, and the question of how different cultural contexts and screen technologies can transform their role in the meaning-making process.

Image Caption: Farrin N. Abbott, Silent Movie Title Card, 2010.