Where are all the Indigenous languages, Duolingo?

Last month, Duolingo – the popular language learning mobile app – released two new languages for their popular language-learning platform: Klingon and High Valeryian. If you have yet heard of these two languages, I won’t hold it against you. After all, Klingon is a fictional language spoken by an alien species in the Star Trek universe and High Valeryian is the popular, again fictionalized, language from the Game of Thrones book and television series.

(Credit: Imgur)

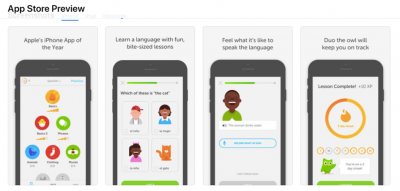

When Duolingo was released in 2011, the available options were German and Spanish for English-speakers and English for Spanish-speakers. The app is gamified meaning that you learn language through mini games and you earn points for being right. These games can be done one at a time or many in one sitting, affording many types of language-learning activities to play throughout the day, during one sitting a few times a week or just once in a while. You can connect with friends who are also learning the same language to compete against them.

Developed by a Carnegie-Mellon professor, Luis Von Ahn, and a graduate student, as first an academic project, the app was meant to be 100% free, accessible (to those with access to a mobile phone with internet and/or data) and fun – because learning languages, especially English, is expensive. Von Ahn explains that this project began as looking for a way to translate the web into all the major languages for free while at the same time creating a platform where people can learn new languages to further help with the larger project of translating the web. Users learn new languages through game-like courses while simultaneously translating parts of the web into that language. In this way, Von Ahn argues that such a business model allows for the user to be gaining value (learning a new language) while offering a service that they are not losing (providing the translations as they participate in the online course).

(Screenshot of Duolingo App as advertised on the App Store in March 2017)

The advent of software technology that allows for almost immediate translation is, on the surface, a potentially enfranchising innovation. Software technology has a significant potential to help historically disenfranchised Indigenous Canadians pass on the languages of their people to new generations. In this context, we need to ask whether designers and creators of apps – the ones who shape ways in which we learn languages by controlling what is accessible and free to us – have any social responsibility beyond making learning languages technologically accessible, convenient, and conducive to building a user base and generating ad revenue. To be clear, I don’t think the intention of Duolingo’s designers is to leave out languages; however, recognizing structural and economic forces at play, one cannot help but to consider and question decision-making processes in adopting Klingon over Cree, for instance.

In 2017, Duolingo finally offered Chinese and Japanese languages, their most requested languages. Duolingo employees have stated that some of these languages have been more difficult to translate into a mobile application course, but the demand has pushed the company to work towards adding the courses regardless. Korean, Mandarin, Japanese, Swahili were also added over the last year with the latter being developed in partnership with the Peace Corps. However not all of the languages were added based on the percentage of the population that use the language, as Welsh was added after a personal letter from the Welsh government. Duolingo announced that they would be developing a course for Arabic speakers to learn Germany because of the Syrian Refugee crisis. Even more so, there has been a move to use this education-based app within educational program and it has already been piloted in some schools in the US. It’s no wonder that Apple listed it as iPhone app of the year in 2013 and is currently used by over 170 million smartphone users.

Knowledge of languages holds power because our society values certain languages over others. Was it not for colonialism, English would have not been the dominant, almost universal language used offline and online. So when we interact with technology on an everyday basis, we can only communicate in a few of the most powerful languages, and not even seeing some languages as an option can potentially contribute to these languages becoming extinct. This has been a problem for a long time with Indigenous languages, and especially languages that rely on oral communication, because writing’s permanence makes it easier to stay in flow throughout time and geographic space.

(Credit: Google Play)

And so, some of the decisions that Duolingo makes reminds us that such mobile apps are first and foremost for-profit apps. Their current business model is supported primarily through advertisements on the app, in-app purchases, paying to have ads discontinued, and paying to complete a certified English test. This is why we are seeing Duolingo more concerned with adding fictional languages to their online course that could potentially bring in broader user base, and thereby increasing their own profits, instead of more of a move to stick with the original idea behind Duolingo of an app being an accessible and free language learning platform for those who wouldn’t have such access otherwise.

The invisibility of indigenous languages in this popular app reinforces the continued systemic racism against indigenous communities. So let’s keep highlighting this issue and asking for this content until designers listen to how much shaping power they have in today’s society for many people. I would also like to start seeing more new apps entering the language market and making a difference, like the mobile keyboard app, FirstVoices.

No people posts are available.