From Asia to North America: Praying Here, There, and Everywhere

by Fatima Haque

‘Illegal Citizen’

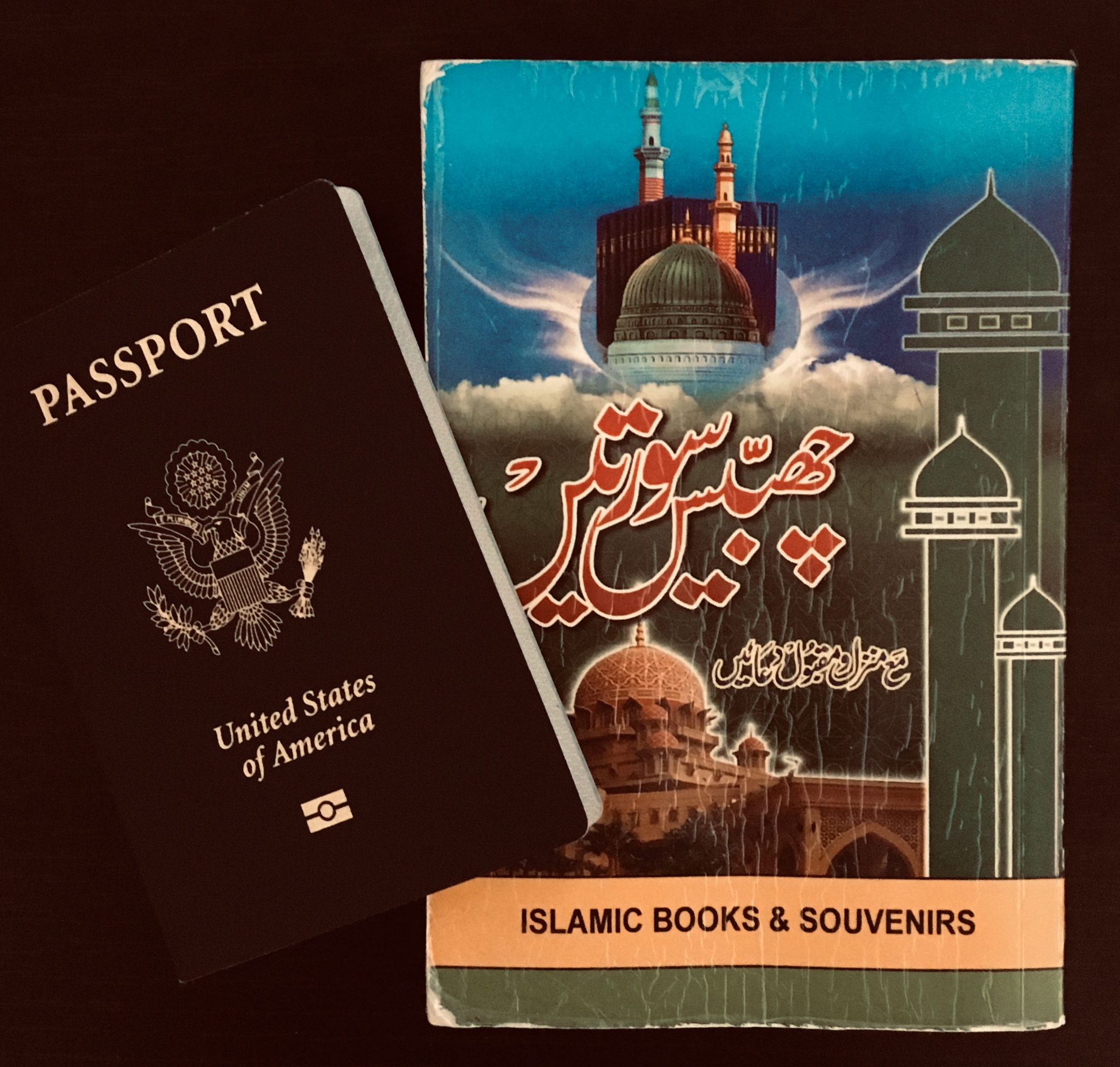

The first time I recall seeing my father nervous was at the U.S. – Canada border. I had noticed this in the apprehension that overtook him as our car approached the border. The process was always the same. While waiting in queue we would begin our routine procedure of concealing: our book full of duas (prayers) into the glove compartment, our janamaz (prayer mat) under the seat, and nervousness with fake self-assurance. When we would reach our turn, my father would hand over five passports with faded gold lettering, three inscribed “United States of America” and two inscribed “Canada”.

Although we carried active and valid passports, questioning was always centered on how we came to obtain the passports and what made us eligible. While we met the legal regulations of obtaining citizenship and owning passports, for my brothers and I through birth right and for my parents through two decades of living, working, and paying taxes in the U.S. and Canada, we would also face social regulations which became visible and tangible at the border. The routine procedure of concealing our daily objects hid away the facets of my family considered foreign – which decidedly were the objects that made us feel like we belonged.

Moving to North America in the mid-1990s after living in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia triggered my parents to consider their positions in a society with differences in cultural practices. They moved from two countries that held Islam at its core to a country that had always seen it as the “other” (Said, 1981). Edward Said (1981) explains in Covering Islam that “Islam has always been seen as belonging to the Orientalist”. The ‘Orientalist’ comes from the larger, “different” part of the world in a world that Said describes as “polarized geographically…in two unequal parts, one called the Orient (east), the other, also known as ‘our’ world, called the Occidental (west)” (1981). This ‘othering’ embeds itself deep in legal structures and social awareness and can present hurdles for immigrants as they seek to fit in. My parents came to navigate these social hurdles through the janamaz.

The Janamaz: Analytic “in” to Community

Islam has five guiding principles that all Muslims must follow and prayer is one of them. Prayers are offered five times a day as a way to remember God throughout the day. It is also an expression of gratitude, a moment of solace, an opportunity for repentance, a meditative exercise, a practice of discipline, and a way to structure one’s day. Other than the mandatory five times a day prayers, there are special prayers at funerals, when making a big decision, during the holy month of Ramadan in which we fast, and on the religious holiday of Eid. I have seen my parents offer all of these prayers. Frequent prayers relate to travelling. When I reflect on my parents’ stories about their travels, Islam is the persistent thread running throughout their stories.

My parents were born and raised in Pakistan. I see Islam as being deeply integrated into Pakistani culture. It informs clothing, values, and economics: interest-free banking is common in Muslim countries (Rammal and Parker, 2013). These realizations led me to consider the material representation of my parent’s values and travels: the janamaz (prayer mat). This mat is where the spiritual and material world converge. At five different points in the day, the janamaz is laid out facing towards the Kaaba – a holy site for Muslims, located in Mecca. This mat is functional as it provides a clean surface to pray on and decorative through the variation of designs, colors and mihrabs. A mihrab is a design in the shape of a semi-circle or a pointed dome like shape that represents the gate to heaven and a directional pointer to the Kaaba (see Appendix B). Most Muslim households have multiple prayer mats, not just for collection purposes but to be able to pray together in large congregations; an essential communal element that helps to create a sense of community.

My parent’s move to the west meant the beginning of an immigration work process. While they were actively creating new existences for themselves, adapting to new ways of life through learning new languages, laws, and where to find halal food, they were also feeling nostalgic. For this reason, they sought out mosques, and enrolled my brother and I into a madrasa, an educational institute that specialized in Islamic education and was held every weekend. There, we learned Islamic history and religious teachings. The mosque is where my parents met and befriended other Muslims. They formed lasting friendships. One mosque was newly renovated. It had a large basement where children would play, events would be held, and parents would chat and sip tea. They communed; meeting weekly after prayers, enjoying each other’s company, discussing topics relating to politics, religion and community work, the next party, tips for newcomers, and more. Praying in a mosque meant togetherness and community that supported my parents in confidently upholding their religious values outside of the mosque and in the face of rising intolerance.

Within my parents’ search for familiarity, they were privy to any indicators of South Asian culture or that someone was Muslim. These indicators were seen visibly, in the form of a Muslim woman wearing a hijab (head scarf) or someone praying publicly. I remember my mother would see a woman in a hijab and say a passing hello or ‘salam’ (peace) to acknowledge their collective belonging to the Muslim community. When we would spend long summer days at the park, someone would bring a large clean sheet to act as a janamaz. The obligatory nature and imperative need to ensure one is completing their daily prayers is the rationale behind seeing a Muslim pray in a park, airport, or mall. While my mother and I, or any other Muslim, would view this as routine, a person unfamiliar to these customs might find them strange.

A Hijab: Deciding to Wear a Veil

My mother decided to start wearing the hijab around the same time she began working for the first time. She held a temporary position at a manufacturing and labelling company for a year before securing permanent employment there. With this employment came a new space for my mother to represent herself. She was the only woman at work who wore a hijab and was visibly Muslim. This had always brought on a series of questions from curious coworkers. She would tell us about the questions her coworkers asked, ranging from “why do you wear that?” to the incredulous “not even water?” during Ramadan. In recounting her stories from work I recall her being confident, willing, and eager to answer questions as both hoping to set an example for my brothers and I and to demystify a religion that can be severely misunderstood.

Living in a post-9/11 world deepened the ‘othering’ Muslims experienced and reframed the Muslim identity into one that was feared. Hate crimes against Muslims in the United States increased exponentially after 9/11, jumping from 28 incidents in 2000 to 481 incidents in 2001 (FBI, 2018). These statistics have never returned to what they were before 9/11 (FBI, 2018). Muslims were harassed physically and verbally on the streets, mosques were defaced, and on a more severe level, many were given detention without charge and faced torture (Alsultany, 2012). This change in climate that every Muslim felt required a thick protective layer of courage. For instance, wearing a hijab in public opened a Muslim woman up to verbal and physical abuse and having her hijab snatched off her head. More recently, the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President gave him a platform to spread his Islamophobic ideologies on a global level. He birthed the idea of a ‘Muslim ban’ and used anti- Muslim rhetoric, connecting the image of Muslims to the words ‘radical’ and ‘extremist’ and claiming ‘Islam hates us’ (Schleifer, 2016). He gained many supporters of this rhetoric which brought a greater increase in hate crimes in the United States in 2016 (FBI, 2018) and fueled similar ideology in Canada. Most recently, Canada’s province of Quebec introduced a secularism bill, Bill 21, banning religious symbols for teachers, police officers, and other public servants (TCRS, 2019). Such a ban introduces legislation which discriminates against hiring and job retention and ultimately limits access to resources for racialized individuals and groups and restricts participation in all aspects of life. Examples of the Muslim Ban and Bill 21 continue to standardize institutionalized discrimination and racism through legal structures (TCRS, 2019). Watching the news, hearing stories, and feeling that ignorance was becoming the attitude of choice toward Muslims, I remember my father once suggesting my mother not wear the hijab to work. Despite his worry, she continued to wear it and I thought about how my mother came to the decision of wearing a hijab in the face of intolerance.

While not uncommon for Pakistani women to cover their head, many of my mother’s friends and family did not. When I asked her about why she decided to put it on, she said it was something she always wanted to do. I considered the confidence that backed my mother’s decisions to work long labor-intensive hours while fasting and to put on the hijab. Her religious values, and decisions to uphold them, were supported by a confidence that came with finding and belonging to a community. It is a difficult feat to uphold practices that are seen as counter to a mainstream culture, especially one that has within it a demonization of Muslims. In belonging to a community, sharing anxieties and fears, and seeing how others practice, one can feel empowered in their decision to practice and display their religion publicly.

For instance, those that choose to wear a hijab or pray in public have not overcome this demonization but practice courage to practice their religion. This empowerment found through community serves as an important tool to navigate social hurdles.

What are you (and we) Looking at?

Sociologist Liza McCoy’s (1995) essay, entitled “Activating the Photographic Text”, discusses the use of photographs and “the socially organized ways viewers constitute what the photograph shows or is of – that is, on the moment of activating the photograph within a particular discourse”. ‘Activating the text’ in a photograph would place focus on the discourses in operation when one is viewing the photograph. In this same regard, replacing the photograph with a janamaz, there are opposing discourses surrounding it dependent on the viewer. To the Occidental west and in the eyes of border guards, discourse involves ‘othering’ and a connection to a slew of threatening and radical identities. To Muslims and Muslim immigrants, the janamaz elicits dialogue surrounding ideas of community and belonging.

For me, the janamaz brought insight into my parents’ stories and served as an example of not only their courage but also the courage of all Muslims, immigrants, and racialized and marginalized people. Although we are met with opposition through media and systemic legal structures, we still find space, create community, start dialogue and pave our own paths to demand belonging My hopes are that in understanding the deeply embedded ideas that uphold social hurdles and how we navigate them, we can work to disentangle negative perceptions of Muslims and Muslims immigrants.

References

Alsultany, E. (2012). Arabs and Muslims in the media: Race and representation after 9/11. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Concertation table against systemic racism (2019). Bill 21 is a case of systemic racism. Retrieved from https://ricochet.media/en/2654/bill-21-is-a-case-of-systemic-racism

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2018). UCR Publications: Hate Crime Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/publications#Hate-Crime-Statistics

McCoy, L. (1995). Activating the photographic text. Knowledge, Experience and Ruling Relations (pp. 181-192). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Rammal, H., & Parker, L. (2013). Islamic banking in Pakistan: A history of emergent accountability and regulation. Accounting History, 18(1), 5-29. doi:10.1177/1032373212463269

Said, E. (1981). Covering Islam: How the media and experts determine how we see the rest of the world. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Schleifer, T. (2016). Donald Trump: I think Islam hates us. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/politics/donald-trump-islam-hates-us/index.html