The End of an Anti-Utopian Era: How Digital Technology is Leading to Dystopia

by Janelle Hamstra

The year is 2073. You’re walking down Bank Street in what used to be Canada’s glowing capital city. On your left, TD Stadium in Lansdowne half stands, and half shrivels to the ground, and there are no more fans left to enjoy sporting events in the community with others. On your right stands the remnants of an abandoned neighbourhood; people haven’t been able to afford to live there for years. Someone passes you, failing to make eye contact not because they’re shy but because they don’t know how to acknowledge human presence in their life. You look up. Something about the orange glow of the sky makes you want to stare at it as long as possible, but you have to look down to avoid tripping on the many cracks in a sidewalk that’s been neglected. It’s time to find some answers. Keep your head down and keep moving. You’ll get to your destination soon if it still exists.

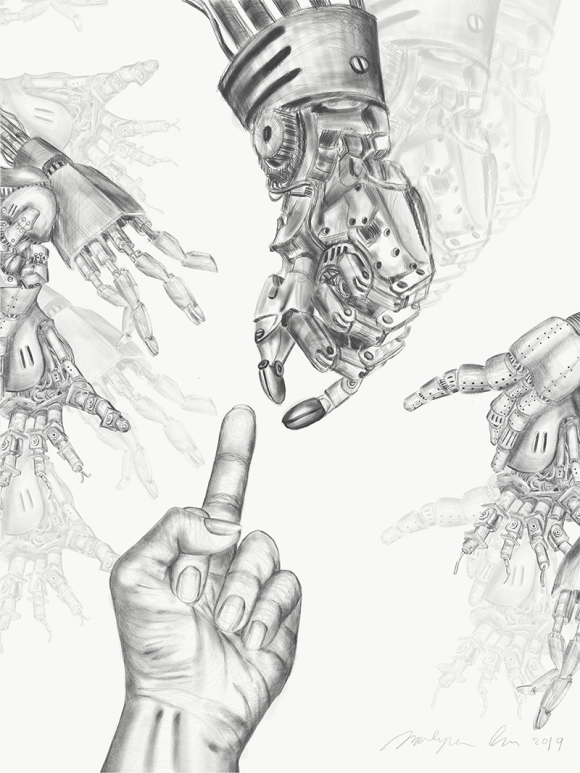

In 2023, we live in a society where digital technology poses no immediate threat to humanity, but that does not mean it never will. Digital technology is advancing at impossible, mind-bending speeds, and its impacts are unknown even to those who build it. By 2073, we will find ourselves living in a dystopian reality primarily shaped by the transformative nature of digital technology. This grim future will manifest through the following key facets: the intrinsic characteristics of digital technology, its profound impact on individuals’ lives, and the far-reaching consequences it exerts on power dynamics and society as a whole.

The Nature of Digital Technology

As you walk, you think back to when you were growing up. Things still seemed under control then—how did all of this destruction come on so quickly?

In “The Information Technology Revolution,” Castells (2011) writes about the striking difference between the information technology revolution and other technological revolutions in history, namely, the industrial revolutions of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One significant marker of the information technology revolution is the speed at which it accelerates and transforms. Castells (2011) attributes this rapid pace of development to the collaborative nature of information technology, as well as its unique flexibility and mobility that allows it to be shared worldwide in seconds.

Castells (2011) proposes a new “socio-technical paradigm” defined by five key characteristics to explain how the information technology revolution profoundly influences both the technological and human sides of society. In short, the five characteristics of this new paradigm are that information is its raw material instead of technology itself, its effects touch every aspect of our lives, and its networking logic means that you need to be part of it; otherwise, you will not be part of society, its based on flexibility, and its technological convergence with older existing systems (Castells, 2011). This paradigm clearly explains why the information technology revolution of today’s age is uncontrollable by nature, meaning the spiral to dystopia could happen at any moment right before our eyes.

Fisher and Wright (2001) describe Ogburn’s theory of cultural lag, which suggests that when new technology is introduced, its effects on society may take time to become apparent. According to Ogburn, this lag between the introduction of technology and its societal adaptation can lead to extreme and often unrealistic interpretations of its impact (Fisher & Wright, 2001). The authors use this idea of cultural lag to soothe societal concerns about the information technology revolution leading to dystopia.

Fisher and Wright’s (2001) article fails to acknowledge the unprecedented qualities of the information technology revolution as Castell’s (2011) article does. As a result, their argument that “society will adjust” is incomplete and not representative of the uniqueness of this revolution. The information technology revolution differs from other technological revolutions and should be treated as such. We are no longer in complete control of technology’s capabilities; instead, it has the unique ability to manipulate our human thought processes, and this capability is growing quicker than we can fathom. This means how we respond and adapt to this revolution, both individually and culturally, will be different from how we have adapted and responded to technological revolutions in the past.

Physical and Psychological Impacts on Individuals

You’re almost there! Parliament Hill. You remember when you were a kid, you used to visit this part of the city every winter for Winterlude and again every summer to see the light show on Centre Block. It used to be so busy on these streets and sidewalks; where have all the people gone?

The digital technology revolution’s most unsettling characteristic is how it affects individuals physically and psychologically. As Douglas Rushkoff explains in Is Our Technology Future Utopian or Dystopian?, there is a digital technology substitute for almost every activity we do (2019). When it comes to our digital diet, Rushkoff argues that not using digital technology at all is best, but since that is nearly impossible, balancing “real world” activities with minimal digital activities is the best way to avoid the harms of digital technology. Digital technology, according to Rushkoff, encourages and enables individuals to live at the scale of a celebrity or a corporation- an exhausting road that leads to failure and stress.

Rushkoff also explains that the internet should be treated like a psychedelic because it alters our realities and perceptions of “real life.” This comparison is compelling and raises the question of whether or not digital technologies should be regulated as heavily as drugs. We use digital technology mindlessly, usually considering how different applications and software will affect our devices but never how they will affect our physical and psychological health. We begin using digital technologies because they are new and exciting, never pausing to wonder if we really need them or if their effects on us will be more positive than negative.

Digital technology is also harmful on an individual level because it encourages physical isolation. While digital technology enables people to connect virtually with one another, it replaces genuine face-to-face connection, an essential part of being in a community with other humans. In this way, you can be part of many online communities but still be plagued with feelings of isolation if you are neglecting a community outside of the virtual sphere. Fisher and Wright (2001) explain that this isolation of individuals is often argued to be destructive to democracy in discussions of dystopia. Digital technology gives off the illusion of a highly connected public sphere where everyone has a voice. Still, there is an enormous gap between those at the centre of the discussion and those on the periphery.

Power Dynamics and Societal Structure

You’ve made it to Parliament Hill! West Block looks different; it is charred by fire but still standing. Speaking of fire, the centennial flame has gone out. You know you normally can’t just walk into Parliament and talk to any government official, but you’re desperate, and it doesn’t seem like anything is exceptionally “normal” right now anyway. So you crack open the spray paint-clad door to Centre Block and head down the hall to where the House of Commons should have a question period- it’s 2:15 on a Thursday. Wait, why is nobody here?

The digital technology revolution will lead to dystopia because of its effects on democracy, power, and privacy. Divisive and extreme responses to the Internet have already manifested themselves in society. The prevalence of cyber-lurkers, privacy concerns, and indecent content online hint at a world where digital technology exacerbates divisions, pushing society further towards a dystopian state (Fisher & Wright, 2001).

As digital technology continues to shape society unchecked by responsible regulation and social adaptation, there is a genuine risk that democratic principles could be eroded. The Internet’s potential for isolating individuals, threatening privacy, and fragmenting society may lead to a scenario where the fundamental pillars of democracy, such as civic engagement and meaningful public discourse, are dismantled (Fisher & Wright, 2001).

As Eduardo Barreto points out in his 2020 lecture on utopias and dystopias, The Iron Heel by Jack London (1908), though it is fictional, illustrates how digital technology can quickly turn a democracy into an oligarchy by isolating people, skewing the public sphere, invading privacy, and spreading misinformation about political issues. 1984 by George Orwell shows us that a dystopian society will not be caused by new technology but by advancing our existing technologies (Barreto, 2020). We see this constantly as our existing technologies become “out of date” and we are persuaded to buy the latest version. We are not above or beyond this imagined reality; it’s closer than we think.

Conclusion

In 2073, the convergence of these three interrelated factors- digital technology’s intrinsic characteristics, its impact on individuals, and its influence on power dynamics- will culminate in a dystopian reality marked by surveillance, social fragmentation, and an erosion of fundamental democratic values. We must anticipate and address these challenges proactively to steer our future away from this grim trajectory. Otherwise, the democratic ideals of an engaged, informed citizenry will be replaced by a fractured, isolated society where the Internet facilitates surveillance and control rather than open dialogue and civic participation.

References

Castells, M. (2011). “The Information Technology Revolution”, from The rise of the network society.

David Pakman Show. May 6, 2019. Is Our Technology Future Utopian or Dystopian? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGPdkP4gdgs&ab_channel=DavidPakmanShow

Eduardo Barreto. 2020. Lecture 3: Utopias and Dystopias [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4BC95DGEYc&ab_channel=EduardoBarreto

Fisher, D. R., & Wright, L. M. (2001). On utopias and dystopias: Toward an understanding of the discourse surrounding the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6(2), JCMC624. https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/6/2/JCMC624/4584220

Author’s bio:

Janelle Hamstra graduated from Carleton University’s Communications and Media program in June 2024. After graduating, she moved back to London, Ontario and launched her small business, Janelle Hamstra Digital Marketing. She is now working hard to build up her business using all of the knowledge and skills she attained in her studies. She loves to learn and be challenged with new ideas.