Reconciliation Realities: The Tensions Charities are Navigating

Reconciliation is a term with deep historical significance and critical future aspirations, particularly in the context of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. Since the 2015 final report from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, sectors across Canada, including philanthropy, have been examining their roles in advancing reconciliation. The Philanthropic Community’s Declaration of Action highlighted this as “an opportune moment” for Canada’s charitable community to lead in reconciliation. However, reconciliation efforts remain complex within the charitable sector, as revealed in our recent survey that explores the roles and challenges charities face in this process.

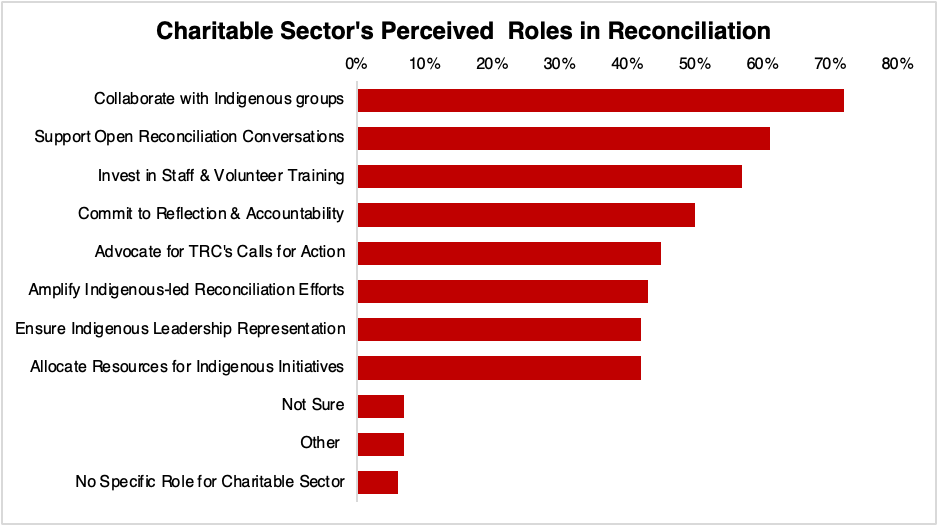

Charities’ Perceived Roles in Supporting Reconciliation

Responses from our panellists indicate a strong endorsement for collaboration with Indigenous communities as the sector’s role in supporting reconciliation, with 72% of participants supporting this initiative. Although significant percentages also back initiatives for open discussions (61%) and training (57%), a comparatively smaller group (42%) prioritizes direct resource allocation to Indigenous initiatives.

Open-ended responses from our survey results showcase a broad spectrum of perspectives on charities’ role in reconciliation. A number of comments draw out an important issue – the conceptual boundary between charity and justice. Some believe reconciliation involves systemic change and justice, while others advocate for a role that involves staying apolitical, focusing solely on humanitarian aid:

“Engage in active decolonization and anti-racism work at levels of policy, programs, processes, etc.”

“Charities cannot be involved in politics – charities are there to help others.”

Some panellists added that the role of the charitable sector in reconciliation should be determined by the mission and location of individual organizations, while others emphasize that the appropriate approach should be to treat all groups equally:

“I think that would vary largely depending on the mission and purpose of the organization and its location relative to Indigenous populations.”

“In discussion with Indigenous clients, I hear that they don’t want to be singled out, simply treated with respect and dignity.”

These varying perspectives highlight that interpretations of the charitable sector’s roles in supporting reconciliation are ideologically charged and highly variable, which is further underscored by their diverse perspectives on the barriers in this process.

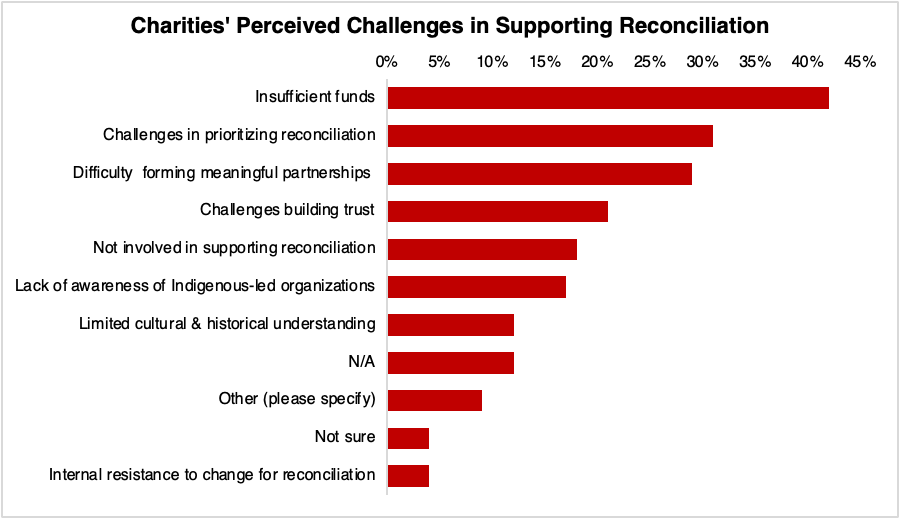

Challenges Facing Charities in Supporting Reconciliation

The perceived barriers in supporting reconciliation efforts identified in our survey could fall into four main categories: physical, psychological, emotional, and ideological.

Physical barriers: Resource challenges are most common, with 42% of our respondents citing insufficient financial resources, 17% noting a lack of awareness of Indigenous-led organizations, and 12% acknowledging limited understanding of Indigenous history and cultures. Additional text responses elaborate on other practical difficulties, such as geographical distances for face-to-face meetings and the challenge of finding Indigenous staff and volunteers:

“There is no time to devote to doing this meaningfully when you are always scrambling with your regular workload.”

“Our organization has not directly been involved in supporting reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. However it is mainly due to our limited staffing and funds.”

“Challenges finding Indigenous artists and culture bearers who are available for work or who have the skills necessary.”

Psychological barriers: Issues of trust and prejudice are also significant, with 29% of our panel respondents reporting difficulty forming meaningful partnerships with Indigenous-led organizations and 21% facing challenges in building trust with Indigenous communities. As shared by some panellists:

“Indigenous clients won’t self-identify as Indigenous due to fear of being treated differently. They just want to be treated as all people. They appreciate curiosity and are happy to educate and inform those who want to learn.”

“First Nation Councils REJECT any linkage to our charitable organization.”

“Racism in the community that supports us. We have both internal and external pressures to not engage. And to be frank, many of these people think any BIPOC or even non white Christian strait long time in Canada communities should be engaged with.”

Emotional barriers: Feelings of guilt or fear of aggravating the situation are also evidenced, with 4% of respondents citing internal resistance to organizational change necessary for reconciliation. As one panellist further explains, they want to do reconciliation right, but they fear that doing it wrong can cause them to appear inactive:

“Fear of taking up space, fear of standing in front of rather than supporting from the back. We want to do this right, but our fear of doing it wrong can cause us to appear inactive.”

Ideological barriers: These might be the most significant factor affecting all other barriers. This involves different understandings of the meaning of reconciliation, what it entails, or what the right approach might be. In our survey, this is evidenced by 31% of respondents reporting that they struggle with prioritizing reconciliation amidst other organizational goals and demands. Additional comments also reveal that internal conflicts and differing opinions on the path forward are prominent ideological tensions within charities engaged in reconciliation. For instance, the inclusion of an Indigenous board member whose views diverge from the mainstream can leave the rest “conflicted and confused.” In another case, there is notable resistance among members when it comes to agreeing on reconciliation strategies, which complicates decision-making and implementation:

“We have an indigenous board member but his ideals do not necessary align with the “popular” ones and this leaves us conflicted and confused”

“Resistance by section of membership (but not all) or differing opinions of what the ‘right’ way forward is.”

Looking forward

As analyzed so far, our survey findings raise more questions than solutions about what role the sector should play in supporting reconciliation, particularly the ideological tension between charity and justice. As noted by Senator Murray Sinclair, the former head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, reconciliation cannot be achieved “when one side sees it as an act of benevolence and one side as a recognition of rights.” Perhaps a starting point is recognizing that both justice and charity support one crucial element: human dignity. In the efforts to build a society where everyone truly belongs, we must accept that reconciliation is an ongoing journey, not a finished project.

Author

Want to receive our blog posts directly to your email? Sign-up for our newsletter at the following link, and follow us on social-media for regular project updates:

- Website: https://carleton.ca/cicp-pcpob/

- Newsletter sign up: https://confirmsubscription.com/h/t/3D0A2E268835E2F4

- Twitter: @CICP_PCPOB

- Instagram: @CICP_PCPOB

- Facebook: @CICP.PCPOB

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/cicp-pcpob/

From Crisis to Caution? Tracking Turnover

In a recent blog, we explored the deepening HR crisis in Canada’s charitable sector, drawing on data from the Charity Insights Canada Project (CICP). Between …

Technology, Human Spirit, and the Ethics of Progress: Charities and AI

A Growing Conversation About AI in the Sector As charities adapt to a rapidly changing world, their relationship with technology, especially AI, has become increasingly …

Stable on Paper, Strained in Practice: The Workforce Crisis in Canadian Charities

The Charity Insights Canada Project has been conducting weekly surveys of Canadian charities to gain insight into the operational realities they face. One of the …