Strange Weather, Shy Elitism and Soul Rebels

We see climate change everywhere.

Its present and looming consequences have begun to reconfigure every aspect of human life, including how we understand our mortal selves, others, and the space we occupy.

People from regions that are currently most impacted by the crisis are already dispersing around the globe. As the climate continues to shift, this phenomenon will surely pick up significant steam.

Considering the contemporary, racist political discourse on migration and borders, which has led to world-altering reforms like Brexit and migrant bans, it is safe to say that we are literally and figuratively just beginning to get our feet wet in an era of profound climate, migration, and cultural volatility.

Daniel McNeil, a Professor in the Department of History at Carleton University, joined the Jackman Humanities Institute at the University of Toronto in 2019-20 as its Visiting Public Humanities Faculty Fellow. As the first person to hold the Fellowship, he has been working on several projects that will bring humanities research about the critical discourse on climate and energy into the public realm for discussion, debate and examination. He took some time out of his busy schedule to discuss his work with the Office of the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

Professor McNeil, congratulations on your Visiting Public Humanities Faculty Fellowship. The work you are doing is complex, but so critical to understanding the contemporary and future realities for those most impacted by ‘strange weather.’ How are reductive stereotypes of racialized people and migrants becoming so prevalent in the era of climate change?

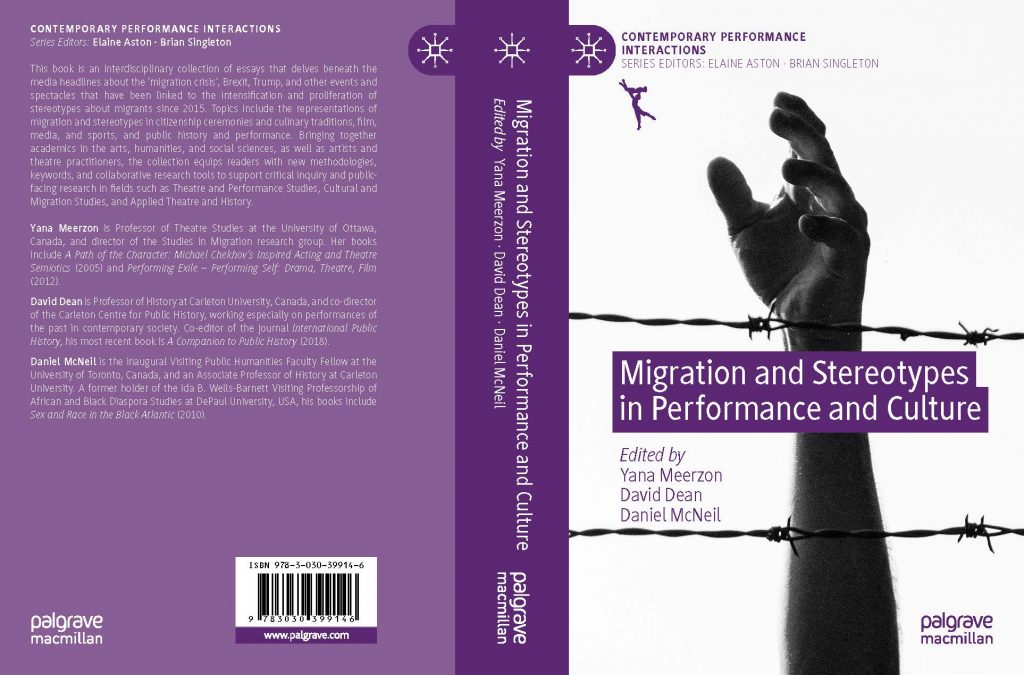

Thanks! In 2017, I helped organize an international and bilingual conference on Migration, Representation, Stereotypes at the University of Ottawa that brought together scholars and practitioners in fields such as Public History, Theatre and Performance Studies, and Cultural and Migration Studies.

Building on the relationships developed at this conference, I co-edited Migration and Stereotypes in Performance and Culture, a collection of academic essays and creative storytelling, with David Dean, co-director of the Carleton Centre for Public History, and Yana Meerzon, Director of the Studies in Migration Research Group at the University of Ottawa. As first- and second-generation migrants to Canada, we were particularly interested in challenging the stereotypes that reduce migrants and refugees to a few, simple, essential characteristics such as irrationality, rhythm, animism, oneness with nature, and sensuality. Chapters consider, for example, how academics, artists, and practitioners have developed pointed rejoinders to contemporary accounts of climate refugees that recycle colonial stereotypes about “primitive Others” in need of aid, expert management, and supervision.

What were some of the inspirations for your second project, How Culture Lives: An Unofficial History of Multiculturalism and Shy Elitism?

On a recent trip to York University to check out a copy of Multiculturalism: What is it Really About? – the 1991 thriller from the Canadian Ministry of State for Multiculturalism – I was greeted by a librarian who drolly remarked that the government guide “looked interesting.” I can’t claim to have offered a suitably smart retort to his deliciously ironic and incisive commentary – “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship” perchance? – but I was alert enough to jot it down as a reminder that multiculturalism has been configured as banal across a range of disciplines and fields of inquiry.

Political Philosophy and Political Science are, perhaps, the best-known areas in which one may apprehend the banalization of multiculturalism at the federal level and the specific programs and research funded through it. Well-known liberal political philosophers have focused on the federal level to more “easily trace the evolution and policy of multiculturalism,” and argued that multiculturalism is banal because it has been incorporated into the same everyday logic of negotiation and power that shapes all domestic politics in Canada. Similarly, political scientists have suggested that the creation of new cadres of community leaders who are familiar with Canadian institutions and practices might be one measure of the policy’s success.

Critical sociologists may be unconvinced by official and corporate narratives that primarily read multiculturalism as a governmental and/or rhetorical aspiration about group cultural rights and formal institutional inclusion. However, they have not only pointed out the banality of institutionalized forms of anti-racism, which seek to manage fearful or morbid responses to migrants ‘flooding’, ‘swamping’ or ‘polluting’ national cultures, and the banality of official and corporate forms of multiculturalism, which are associated with shiny, happy, and glamorous images of multiracial or multicoloured groups. They have also suggested that lived multicultures in postcolonial cities and provincial towns may represent a “banality of good,” and drawn attention to the moral economies and creative possibilities in spaces in which one set of habits flows into the others and all of them are altered by that encounter.

So, your project considers how multiculturalism, immigration and race relations have been made commonplace or trivial. What do you mean by ‘shy elitism’?

I coin the term ‘shy elitism’ to grapple with an intriguing mix of academic credentialism and anti-intellectualism that can confine and define the study of immigration, multiculturalism and race relations. On the one hand, the spectre of shy elitists influences the promotion of spokespeople with validation and credentials from elite universities as well as the tone of their progressive campaigns against racism in Canada. This type of shy elitism helps explain why politicians and social scientists acknowledge that their work on racism in Canada doesn’t say anything new to racialized communities, but that it is necessary to translate the experiences of minority communities in the safest, most bland terms for decision-makers in the upper levels of Canadian society.

On the other hand, shy elitists also claim that it is problematic for an ‘intellectual elite’ to develop museum exhibits, newspaper articles or applied research that includes metaphors, irony or literary references. They may, for example, deem it too ‘esoteric’ for politicians to allude to ancient Greek drama in their speeches to ‘ordinary Canadians.’ To paraphrase the cultural critic Mark Fisher, this type of shy elitism runs the risk of assuming that it is ‘elitist’ to treat people as if they are intelligent and ‘democratic’ to assume that they have a sixth-grade reading level.

This sounds like such an important project, but also a very challenging one. Is it correct that your third project will rely on foundational thinkers such as Stuart Hall to understand the influence of underground rave music, particular music scenes and pirate radio had on certain activist-minded thinkers and social movements?

If one project focuses on how multiculturalism contributes to stereotypes of Canada as a bland, risk-averse nation, another thinks about how we can honour and update the lively and radical work of Stuart Hall and other vernacular intellectuals. It demonstrates how Hall inspired colleagues to grapple with an anti-hierarchical tradition that applied the politics and poetics of ancient Greece and Rome to the praxis of revolutionary workers and anti-colonial movements.

I’m currently writing a book about a couple of critics who share Hall’s ability to deepen our interest in the power of art, music and culture that is questioning, daring, and visionary. One of the critics I’m discussing is Paul Gilroy, perhaps the best-known student of Stuart Hall at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural studies in Birmingham and arguably the most influential intellectual writing in the United Kingdom. The other is Armond White, aka “the Kanye West of film criticism” and “the most notorious film critic in the digital age.”

Oh right, the fierce critic who is known for holding very different opinions from his peers and who is consistently at odds with the zeitgeist.

That’s right, although Armond would probably argue that he is in tune with the real spirit of the times – the problem is that too many people are behind the times and unable to appreciate the insinuating rhythms of the street because they have sheepishly followed the positions espoused by cultural gatekeepers in the mainstream media.

In studying the parallel lives of Gilroy and White, I’m mapping the long careers of critics who came of age after the shifting of the racial architecture in the United States and the United Kingdom in the late 1960s, and were inspired by creative artists who translated the UN declaration of rights into clarion calls to emancipate ourselves from racial hierarchy and mental slavery.

After demonstrating the power of their early work in revolutionary newspapers and magazines in the 1970s, I’m also investigating how they resisted “Trump-like edifices” that force-fed the public baroque fantasies about a white millionaire vigilante “taking back the streets,” and critiqued minority artists and critics who entered into mainstream cultures in the 1980s and 90s as speaking and shrieking commodities.

Finally, I’m analyzing their late style and coming to terms with their pessimistic readings of contemporary popular culture in the digital age, and their concerns about the debasing and deskilling of Black music and the regression of film culture in the twenty-first century.

Clearly, you’re keeping busy in your Fellowship. Broadly, what do you hope to take away from this experience in which you are demonstrating the central role the Humanities and the Arts have to play in fighting for social and ecological justice?

At the Humanities Institute, I have an incredible opportunity to work with a collegial group of students, scholars, artists and activists whose intellectual scope moves between formal academic research and public communications. In our weekly meetings, we seek to generate deep and sustained reflections about our research theme of ‘strange weather’ and the study of energy, climate, and the environment. As a result, I’ve had the opportunity to debate what we might learn from the soundscapes and landscapes that inspired young soul rebels and their politically infused acts of pleasure. I’ve had the time and space to discuss how morbid, mournful, or melancholic forms of energy have powered narratives of decline, protection, and regression. And my work has been transformed and boosted by stimulating work in the humanities that considers how utopian desires have overflowed from their national and generational containers and been transmitted across time and space.

Thanks so much for your time, Professor McNeil.

You’re very welcome.