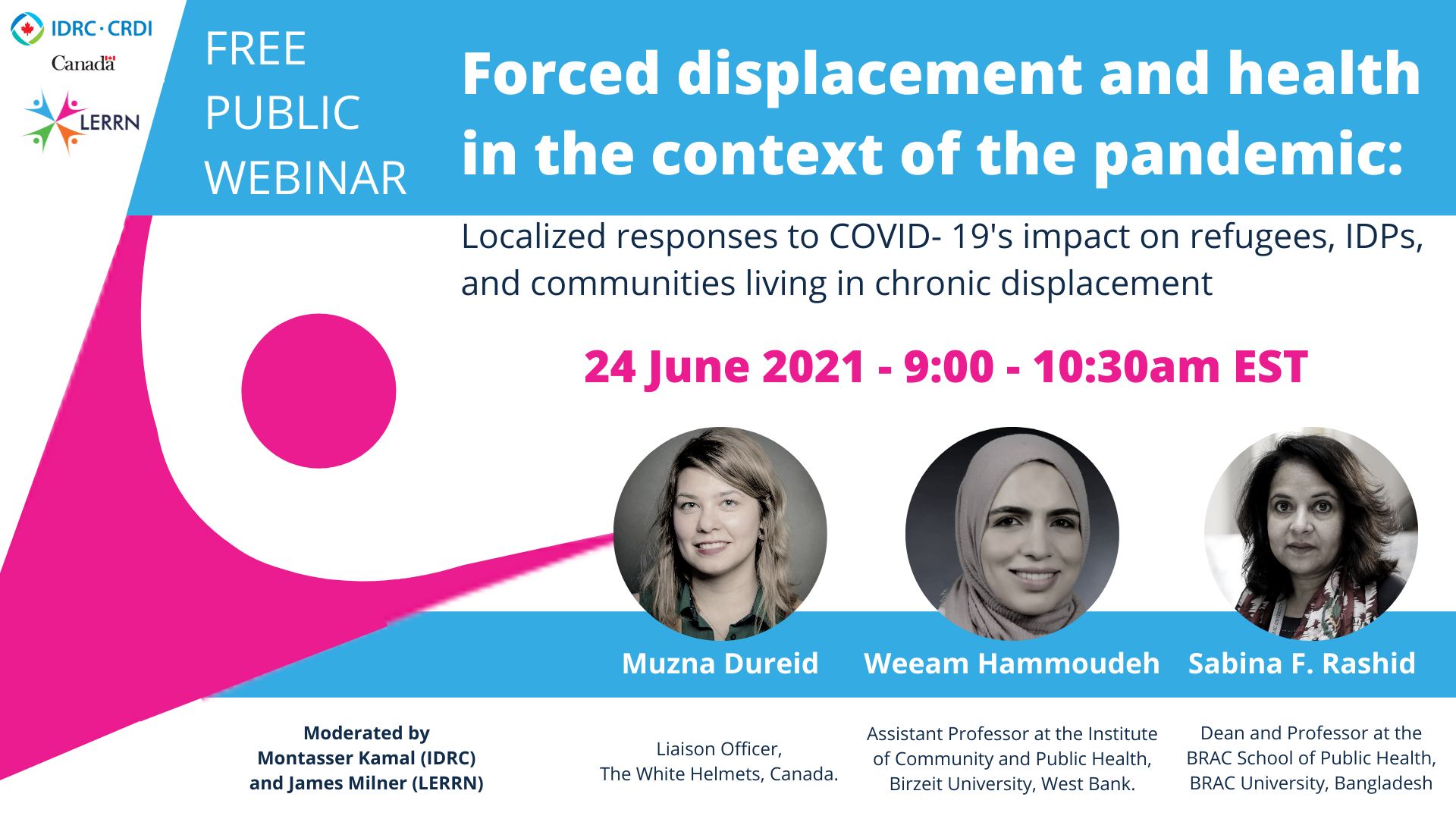

On 24 June 2021, LERRN and the International Development Research Center (IDRC) hosted their seventh and final webinar in the LERRN-IDRC webinar series on Forced Displacement. This webinar, drawing on lessons from Bangladesh, Syria, and the West Bank and Gaza, focused on health systems and the COVID-19 response. Panellists Sabina Rashid, Weeam Hammoudeh, and Muzna Dureid, and co-moderators James Milner and Montasser Kamal examined what the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic reveals about how health systems respond to the needs of the forcibly displaced and how localized actors and approaches can improve access and health outcomes for refugees, IDPs, and other forcibly displaced people.

Sabina Rashid, Dean and Professor at the BRAC School of Public Health, argued that the overly clinical response to COVID-19 in Bangladesh – orchestrated primarily by public authorities— served to further marginalize the country’s refugee community. Like other jurisdictions, the public response to the pandemic involved widespread lockdowns, hospital closures, reduced services, and public health campaigns to promote social distancing, quarantine, and other sanitation measures. While these measures might be appropriate in some contexts or with certain groups, Rashid emphasized that they are not necessarily appropriate for the 800,000 mostly Rohingya refugees in the country. A key issue is the unique socio-linguistic particularities of the refugee community. Many refugees, for example, do not read or speak Bengali, which limits the flow of information about service provision and public health measures. Rashid argued that such oversight could be remedied by utilizing existing refugee networks and channels – including the refugee doctors and medical personnel that many in the community prefer.

Rashid also highlighted how the COVID-19 response ignored the material conditions of refugees. Most refugees in Bangladesh live in crowded camps. Kutupalong, for example, has almost 600,000 residents and is now the world’s largest refugee camp. In this context, measures like social distancing, quarantine, and other sanitation measures make little sense and create an unattainable standard for refugees. Weeam Hammoudeh, Assistant Professor in the Institute of Community and Public Health at Birzeit University, highlighted similar issues in the West Bank and Gaza. While only 10-15% of Palestinian refugees in these areas live in camps, many still reside in crowded conditions where social-distancing and other public health measures are difficult to achieve. Hammoudeh also underscored the economic effects of the lockdown. In regions characterized by widespread poverty, the inability to work placed additional pressure on refugee households.

Despite the limitations of the COVID-19 response, panellists were in agreement that the emergency has had some positive impacts on health services, particularly in terms of improving the participation of the displaced and the localization service delivery. Across these unique contexts, lockdowns, closures, and travel restrictions combined to create more space for displaced communities to mobilize and take a greater role in service provision. Muzna Dureid, Liaison Officer with The White Helmets, detailed how the role of her organization in northwest Syria has evolved since the beginning of the pandemic. In a region where public services and infrastructure has been devastated by a decade of conflict, COVID-19 has added another layer of complexity. In response to the pandemic, the White Helmets, a volunteer-based organization well-known for its heroic medical evacuations, have mobilized to support communities and the health sector by collecting and disposing of personal protective equipment (PPE), disinfecting schools, hospitals, and residences, conducting awareness campaigns, providing burial services, and through the production and distribution of oxygen. Since the pandemic began, the White Helmets have strengthened partnerships with donors and other international actors who are eager to maintain connections in the region. And most recently, they have received funding from Humanitarian Grand Challenge to increase their production and distribution of PPE, including face shields, surgical gowns, and other disposables to households and medical facilities. In the West Bank and Gaza, Weeam Hammoudeh identified a similar trend. She suggested that COVID-19 seemed to create a spark among Palestinian refugees who have since mobilized to deliver medicines and other essentials to people in need, organize checkpoints, and offer other critical services.

Challenging the overemphasis of concepts such as ‘resilience’ that are used to describe the capabilities of individuals and local systems to adapt to ever-changing global political-economic conditions without thoroughly engaging in the structural factors that induce and sustain these realities, panellists turned to what lessons can be learned to improve access and health outcomes for refugees, IDPs and other forcibly displaced people.

First, panellists stressed that the participation and inclusion of the forcibly displaced must be the starting point. This is not only because these communities have capabilities and knowledge that is critical to designing effective interventions, but also a question of respecting the dignity and autonomy of the displaced.

A second related point, however, is that the diversity of perspectives must be recognized. As Hammoudeh emphasized, in Palestine, there are of course men, women, the elderly, and people with disabilities, but there are also multi-generational refugees, newer refugees, individuals in camps, rural and urban areas, as well as people living in active conflict zones – all of these perspectives are valuable and must be heard.

Third, panellists suggested that donors and other international actors should commit to sustained engagement with displaced communities and their organizations. The White Helmets are just one example of a local/national organization that has been able to evolve in light of growing donor relationships, but as Dureid argued, increased investment can create vibrant networks of grassroots actors who are able to identify and act upon their own priorities. This point echoed arguments made during the December 2020 LERRN-IDRC webinar on refugee leadership.

Perhaps the most important lesson, however, is that a narrow focus on health (or any single sector) risks the broader systemic issues that impact the well-being of those affected by forced displacement. Even the world’s best health system cannot protect individuals from violence, poverty, or marginalization.

These points underscore the importance of solidarity, participation, and human rights-based approaches in preventing and responding to forced displacement. Points that echo Barbara Harrell-Bond reflections in her foundational book, Imposing Aid (1986), more than three decades ago. Critiquing what the scholar referred to as “discriminatory ideologies,” Harrell-Bond research on the South Sudanese refugee crisis in northern Uganda showed how the attitudes and practices of international humanitarian actors resulted in top-down responses that were not only expensive, ineffective, and wasteful, but also undermined the role and creative energies of host and refugee communities. The scholar challenged the idea that international actors possessed universal knowledge and techniques that applied to every context and advocated for more participatory approaches to aid delivery that relied upon the expertise and knowledge of host and refugee communities. In her view, this was not only a practical way to improve service delivery, but a matter of accountability, solidarity, and human rights.

Bangladesh, Syria, West Bank, and Gaza are much different than the northern Uganda of the 1980s, but as panellists highlighted, COVID-19 revealed the pervasiveness of anti-participatory approaches to forced displacement responses.

The solution might not be straightforward, but as Montasser Kamal, Program Leader for Health Research Partnerships at IDRC, emphasized, “We should resist the urge to run to quick pre-packaged fits-all fixes.” Rather, Kamal concluded, the focus should be on establishing trusted relationships between affected populations and decision-makers, strengthening the role of research in understanding differential needs to support more inclusive and gender-equal responses and recovery, and supporting countries and communities to find their own contextually-informed pathways to solutions.

Click here to watch a full recording of this webinar.

This report was prepared by Tyler Foley, PhD Student, Carleton University.

The LERRN-IDRC Webinar Series on Forced Displacement is coordinated by Jennifer Kandjii, LERRN Research Officer. For further information or ideas please contact us here.