Available in عربي Français Español

Event details and recordings available here.

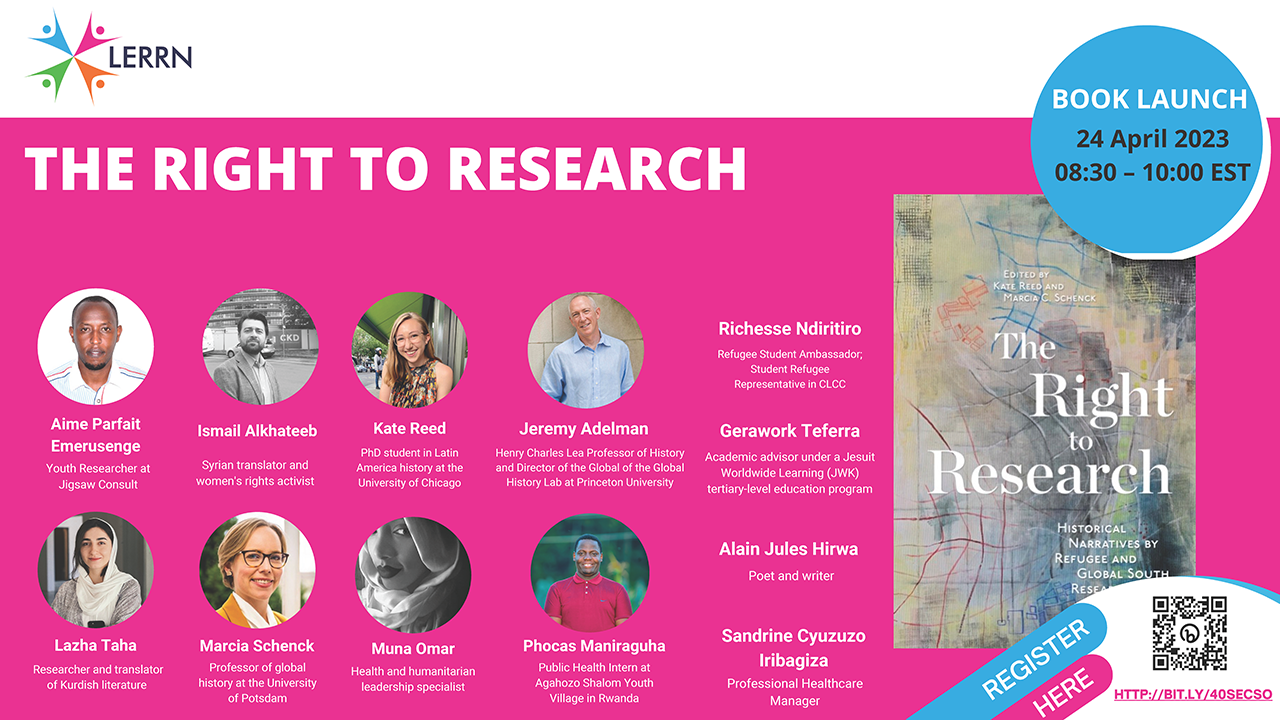

On Monday, April 24th, viewers across 29 countries attended the virtual book launch of The Right to Research anthology published by McGill-Queen’s University Press as part of their Forced Migration Studies Series. The conversation, moderated by Professor Jeremy Adelman (Princeton University), revolved around contributors’ and editors’ personal experiences as historians, the challenges of the concept of the “right to research,” and the opportunities and difficulties they face while striving to change the way historical scholarship is produced while in displacement.

Jeremy Adelman opened the discussion by asking how this anthology came to be. Professor Marcia C. Schenck, one of the book’s editors, responded by stating that the anthology is an effort to confront the suppression of particular accounts and collections of historical records. These silences on the archival and narrative production level were initially drawn to Prof. Schenck’s attention in 2016, when she worked as a teaching assistant for a global history course taught to refugee learners in Kakuma Refugee Camp. Gerawork Gizaw, one of her students who went on to become a contributor to the volume, raised the fact that refugees and displaced people were largely missing from large-scale historical narratives, and that even fewer refugees were present as historians authoring those narratives. With the Global History Lab at Princeton University, this prompted her to develop the Global History Dialogues Project, which trains student-researchers with all kinds of relationships to citizenship and statelessness in oral history research methods, and supports them in conducting original oral history research on topics of their choice. It was from the context of this course that all of the essays in The Right to Research first developed.

Jeremy Adelman then turned to some of those research projects. Alain Jules Hirwa delved into how hip-hop culture in Kenya can function as a mental migration and an expression of political dissent. Gerawork Gizaw focused on refugee education in the Kakuma camp by looking at the historical perspective of education quality versus expansion. Jeremy asked the participants to expand on the idea of becoming a researcher for people who are from the Global South or forced migration background. For Lazha Taha, becoming a researcher proved that her interests in Kurdish photojournalism and archive preservation hold professional and academic value. Muna Omar, as a person from a refugee and marginalized background, expressed the systemic challenges and biases within academia. For her, becoming a researcher allowed her to start dismantling the mentality that normalized the unfair treatment of refugees in Yemen. For Sandrine Cyuzuzo Iribagiza, becoming a researcher who analyzes Intore traditional dance involved working with others and using various sources to create a final product.

Expanding from the position of the researcher, Ismail Alkhateeb emphasized the importance of empathy and active listening in building a comfortable and safe environment for interviewees when conducting oral history research. As Richesse Ndiritiro echoed, the researcher is not a passive entity and their personal experience as a refugee and a researcher can help avoid biased narratives in research.

The concept of “the right to research” is a reference to Arjun Appadurai’s essay with the same title, in which he defines the right to research as a “right of a special kind,” a right to “make disciplined inquiries into those things we need to know, but do not know yet” (p. 167). This right becomes fundamental to leading a meaningful life in a democratic society as a citizen. However, Marcia Schenck drew attention to necessary additions to Appadurai’s definition: “First of all, the right to research in the sense of inquiring into the things that we do not know yet and finding out about them in a systematic way is fundamentally important … to people in all sorts of different spheres of life.” Indeed, the concept becomes even more critical for those who are partially or fully outside of the regimes of citizenship. Additionally, Marcia Schenck stated, “research is not something that happens in your individual room, by yourself, but it is something that happens in exchange with your interview partners, colleagues, and collaborators.” Gerawork Gizaw comments on this second aspect and states that not having access to this right means outsourcing the understanding and problem-solving capacities of an individual. The right to research, then, involves having the space to tell one’s story and share one’s experiences, especially in the context of refugee camps. In other words, the right to research is interpersonal and conversational.

After the panelists shared their personal experiences as researchers, they reflected on the impact of their research across academic, community, and policy spaces. According to Aime Parfait Emerusenge, studies included in the anthology provide a blueprint for collaboration between the Global North and Global South while highlighting the importance of discussing social realities, including displacement and cultural preservation. Kate Reed expanded on the idea of a conversation because each section in the anthology starts with a letter from the author addressing the reader, which acknowledges the position of the reader as a stakeholder in historical scholarship. Additionally, Kate Reed frames the anthology as an archive because “each contributor built their own archive of interviews with people in their local communities in contexts.” Phocas Maniraguha, for example, conducted research on traditional healers in East Africa, which highlights the importance of preserving the knowledge of older generations and making it accessible to younger generations and the wider community. Phocas Maniraguha’s research bridges the gap between academic researchers, policymakers, and community practitioners.

The Q&A portion of the event tackled various topics ranging from ethical research with traumatized groups to the limits of the “right to research.” While Muna Omar stated that the interviewees could feel safe more easily with researchers from marginalized backgrounds, Sandrine Iribagiza emphasized that the right to research as a concept goes beyond the boundaries of academia. Lazha Taha commented on the importance of this anthology in the field of forced migration and historical scholarship: “This book is a good way to learn about a diverse set of people from the world talking about their lives and struggles, and that’s what will make us contribute to each other’s shared knowledge.”

To conclude the event, each contributor and editor shared their final thoughts about what they’d like listeners to walk away from the conversation with. Sandrine Iribagiza shared that research plays a crucial role both at a personal level and in our societies at large, and that we need to share research-based knowledge to inform policy. Ismail Alkhateeb shared his aspiration for an “inclusive history” that gives “agency to those who are, in traditional research practices, framed as victims or treated as subjects of studies.” Phocas Maniraguha shared his hope that more young people in Eastern Africa are able to engage in research and build community. Lazha Taha noted that projects like this expose us to the diversity of the world, but also to shared problems and solutions. Alain Hirwa encouraged us to approach the world around us with greater curiosity and a researcher’s sensibility, to engage in the creation of our own research and archives. Richesse Ndiritiro noted that detailed historical research can open up the question of “who is a refugee” to policymakers, and that involving refugees in research can help address the challenges displaced people face. They are not just part of a vulnerable population, but crucial contributors and authors of research. Aime Parfait Emerusenge emphasized the importance of research raising up untold stories and helping us take action. Muna Omar noted that refugees are often seen as “static numbers” in the news, and that research and history writing can help illuminate the humanity of these individuals and create better humanitarian responses. Gerawork Gizaw addressed the issue of education and mobility. Technology has helped him obtain research training and other opportunities without mobility, and he hopes that a culture of doing research also develops as a result of this communication and exchange. Marcia Schenck stressed an understanding of the right to research as dialogical, in which refugees and others on the move have the ability to conduct a systematic inquiry, but also the ability to be taken seriously as producers and bearers of knowledge. Much of the onus falls on those of us within academic and policy spaces to shift the institutional, funding, and epistemic landscapes to create more horizontal, diverse discussions. Kate Reed, drawing on the conclusion of the anthology (which was coauthored by all of the contributors and editors), reflected on the importance of continuing to engage in work that facilitates new forms of knowledge production, while always remaining critically attentive to their limitations, and invited the audience to continue the conversations opened by the book and the webinar.

This report was prepared by Irem Karabağ, LERRN Project Writer, and Kate Reed, co-editor of The Right to Research Anthology.