The Navajo-Apache Are Ancestral Chipewyan Canadians: New Support for Two Routes to the American Southwest

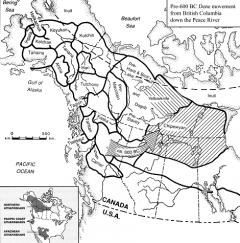

Dene distribution in the North with movement to West Coast ca. 500 AD

The Athapaskans, or as they call themselves, the Dene or People, occupy the largest indigenous area in North America, from Alaska east to Hudson’s Bay and south to Oregon, California and the American Southwest (lower left inset). In Canada the Dene inhabit parts of the four western provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba), plus the Yukon and Northwest Territories. The Chipewyan occupy the largest part to the east (hatched area on map). In the United States and across the Rockies from the Pacific Dene in Oregon and California, the Navajo and Apache Dene inhabit part of the American Southwest, with the Apache extending into Mexico.

About 500 AD the Central Plateau Dene of British Columbia left for the Pacific Coast, becoming tribes like the Tolowa and Tututni. An ancient legend mentions the Apache originating in the far north, once living in ice houses on the shore of a great inland sea. Could this be Lake Athabasca in Saskatchewan north of the Great Plains or Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories further north? Both are in non-mountainous Chipewyan areas, but the Navajo claim a mountain origin, which is possible if we accept their ultimate beginning in Alaska rather than in the Southwest.

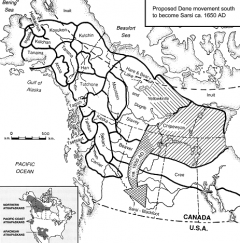

Dene cross Rockies to become ancestral Barrenland Chipewyan ca. 600 BC

Much earlier than the Dene move to the Pacific Coast, others crossed the Rockies about 600 BC through the only viable pass, that of the Peace River from British Columbia to Alberta. Further north the Liard River drains a huge basin through the Rockies, but its canyon is not only unnavigable but bears no sign of transit. The wide and gentler Peace River Valley leads right to Lake Athabasca, the winter range of the Beverly caribou herd, with many ancient Chipewyan sites like Karpinsky and Peace Point along the way.

From Lake Athabasca the early Chipewyan followed the Beverly herd migrations into the Barrenlands, lancing the caribou at water crossings and eventually occupying the full herd range on a seasonal basis. The Dogrib and Yellowknife occupied their caribou ranges later, based on radiocarbon dates of the earliest Chipewyan in the Beverly range. From here the ancestral Chipewyan moved east to occupy the Kaminuriak caribou range of Nunavut and northern Manitoba (extended right hatching)

Dene follow Rockies Foothills to SW Alberta become Sarsi at 1650 AD

About 1650 AD the Sarsi Dene or Tsuu T’ina followed the Alberta Rockies foothills to find a safe haven with the Blackfoot from the Cree. Although unrelated to the Chipewyan trek south I wish to show a common practice for all Dene living within or beside dominant cultures, and a likely recurring practice in Wyoming, Colorado and Southwest sites.

While kinship and language were preserved, Sarsi subsistence and tools became indistinguishable from those of Blackfoot. The Dene were not only inveterate tool borrowers, but their mobility required the use of many disposible flake tools instead of finished tools, traits also common to the Ute further south.

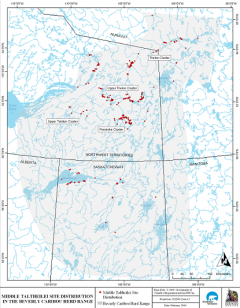

Widest site distribution: 355; 23 dates in Middle Chipewyan phase under ideal conditions

The Middle phase of the ancestral Chipewyan in the Beverly range had the greatest expansion with 355 hunting camps scattered from the caribou calving grounds in the northeast to Lake Athabasca in the southwest. During a period of warming climate the more venturesome of the southernmost Chipeywan began seeing bison wintering in an advancing aspen parkland.

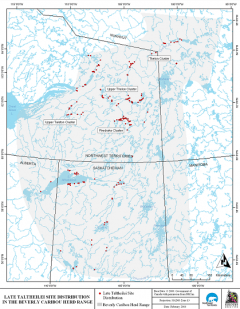

Narrowest site distribution: 247. 38 dates in Late Chipewyan phase with contraction south to bison hunting with bow and arrow

Caribou herd following dwindled slightly in the Late phase of the ancestral Chipewyan, with more sites between Lake Athabasca and the Churchill River of northern Saskatchewan suggesting the hunting of more forest animals (bottom of slide). Hunters adopted the bow from the western Dene, marked archaeologically by crude asymmetric tanged arrowheads.

At the time of their trek south at 800-1200 AD they copied Prairie Side-Notched points. The symmetry and smaller size of these points improved the accuracy and range of bow hunting of distant caribou on the open tundra away from water-crossings.

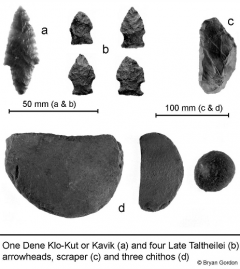

(a) Brit.Col./Yukon Dene Kavik point

(b) Barrenland Late Chipewyan Prairie

S-N points show contact with Plains bison hunters

(c) large scraper

(d) chitho scraper discs or cobble spalls carried S

There are archeological markers for Dene in all areas where they migrated. The earlier 500 AD Dene migration to the Pacific Coast was signalled by the Klo-Kut or Kavik point which occurs only west of the Rockies (upper left). East of the Rockies from the northern tundra into the forest, Prairie Side-Notched points were used after 800 AD (center), occurring in sites even closer to the winter range of the Plains bison than the Middle Chipewyan phase of the previous slide. Carried with these points were a variety of chitho scrapers ultimately traceable all the way to their Alaskan origin. Alaskan chithos are simple cobble cortex spalls with crudely sharpened edges for working hide.

In the Barrenlands, chithos became sandstone tablets fashioned into thin rounded discs with crudely worked peripheries (bottom) Quartzite cobbles and sandstone tablets were simple tools of the moment, readily available and easily discarded. Chithos are traceable south to central Saskatchewan, but with the relative absence of sandstone exposures and change of game to bison with much heavier hides, it is likely chithos were abandoned in favour of the metapodial fleshers used by the Plains Indians. Large quartzite scrapers were also part of the toolkit (upper right).

Chipewyan move to Southwest

- Based on spoke-and-rim bison migration over tall and mixed grass prairie to calve on western short-grass

- This allowed Dene to take a Plains or Foothills route to become Plains Apache about 1100AD.

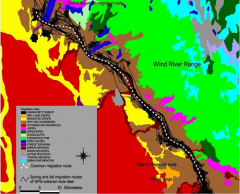

The concept of herd following has been misinterpreted by anthropologists believing that hunters accompanied the herd, an absurdity because families cannot maintain its daily pace. It means following the path of the herd a month or so later, intercepting it on its return at water crossings, canyons and places where brush and rocks for building drivelanes were readily available. This was done in spring and autumn along the migration path by different bands of the same tribe. Stratified bone levels demonstrate this pattern for 8000 years, including the 2600 year-long Chipewyan occupation. On their trek south to become the Navajo and Apache, they likely continued herd following, but switched to bison, adapting to its spoke-and-rim migrations in Canada.

Here, most bison calved in the central short grass prairie, crossed the bands of mixed and long grass prairie and wintered in the shelter of the semi-circular aspen parkland that bent northwest from southern Manitoba across central Saskatchewan to the Rockies of western Alberta (top of slide). Long grass prairie was cropped during spring and autumn migrations. In this manner it was possible to follow many herds east and west across the sequence of ripening grass. The Dene could avoid hostile neighbours by switching herds as they moved south along the Foothills over several centuries to evolve into the Plains Apache about 1200 AD.

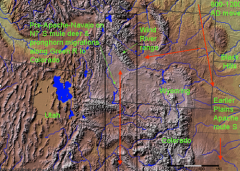

Drought or enemy forced Dene into Wyoming Basin towards Green River

The Plains route was discontinued near the Black Hills of South Dakota due either to hostile neighbours or diminishing bison due to drought. Movement of bison into the Rockies during drought may have pulled the Dene into the Wyoming Basin via the widest opening in the entire Rockies. Here, thousands of undated and unassigned sites must be examined for Dene presence.

Some are called Ute or Comanche. This basin and those further west along the Green River also had mule deer and pronghorn which migrate north and south to Colorado (rectangle). In their herd following tradition the Dene likely also hunted these animals.

Some likely hunted migratory mule deer near Wind River range

Mule deer do not migrate as far as pronghorn but also follow the Green River, even through bottlenecks where sites have been excavated. Hopefully, Wyoming archaeologists will combine the many unpublished cultural resource management reports in this energy-rich area to see what effect both of these numerous migrators had on hunters. Further south, mule deer and pronghorn were extensively hunted by the Navajo, with pronghorn corrals in many areas.

Others may have hunted pronghorn migrating N & S across W Wyoming along Green R. to W Colorado. Further migration S brought Dene to Four-Corners to become Navajo and Western Apache about 1200AD

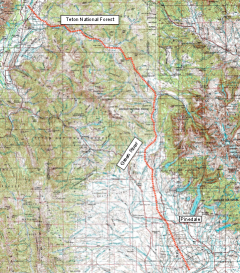

Currently, there are more pronghorn in Wyoming than people, and it is likely that they were more plentiful in the past when they were less restricted by development. Their main route goes across Wyoming from the Teton National Forest to Colorado, with known late sites now attributed to Ute.

We must re-examine these sites for possible Dene traits to be listed on my final slide. Perhaps the Green River was the path of both Dene and herds to the Uncompahgre Plateau of western Colorado. The Navajo homeland of the San Juan River and Four Corners are close by.

Some sites along Green River may be Dene rather than Ute

The Green River becomes canyonlike as it enters Utah and Colorado, channelling mountain sheep, pronghorn and bison past hunting overlooks. In light of ‘old wood’ problems, known Ute collections in this area should be re-examined for Dene traits because they did reach the Four Corners to become Apachean.

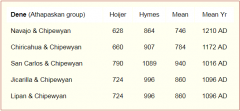

Northern and Southern Athapaskan language divergence in years using Hymes/Hoijer 1956 baseline

Besides mythology, linguistics, archaeology and genetics (Y male chromosome and mtDNA) support the vastness and depth of the 1000 year-old, 1500 mile-wide gap between the American Southwest and northern Canada. Linguists Hoijer and Hymes calculated the divergence in years between the Chipewyan and five Apachean languages at 1096 to 1172 years, a split agreeing with my 800-1200 AD radiocarbon-dates of when I think some Chipewyan left Canada to become Apachean. In addition I found 217 Chipewyan and Apachean common words in nine linguistic sources with the following correspondences:

Apache-Chipewyan-Navajo = 18; Apache-Navajo = 32; Chipewyan-Navajo = 41 and Chipewyan-Apache = 18. I interpret the same number of correspondences (18) between Apache-Chipewyan-Navajo and Apache-Chipewyan and the highest number of Chipewyan-Navajo correspondences (41), plus the greater dissimilarity between Chipewyan and Apache, as showing the earlier arrival of the Plains Apache via a Plains route, and the later arrival of the Navajo and Mountain Apache via an Intermountain or Rockies route through Wyoming.

Misconceptions on Dene arrival

One cannot date Dene arrival in the Southwest by trying to extend Spanish historic records into the Protohistoric. One must identify earlier Apachean collections based on their Canadian ancestry. To do so we must drop existing misconceptions:

- Avonlea with its distinct arrowheads are Algonquin in origin and earlier than the Dene trek south;

- Some archaeologists retain Dene ties to Utah’s Fremont and Promontory cultures, but these had genetic haplogroups C and D while Dene is A;

- Promontory-Fremont was allegedly replaced by Ute at 1300 AD, but we know ‘old wood’ delays the dating of Numic Expansion;

- Ute and Dene sites, wikiups, flake tools and Side-Notched points are similar but unrelated;

- Promontory moccasins had heel tabs, but these are widespread and common, while early historic Dene had tabless trouser-moccasins;

- The Dismal River Aspect is far too late and represents a reverse movement;

- Shield Warrior motifs are too common for cultural affiliation, but Montana’s 1000 year-old Shield site and turtle motifs like those in the Southwest suggest movement from the main route south; and

- Post-1500 AD is too late for Dene arrival because it is based on the presence of corn, hogans or pottery, which the seasonally-moving Dene could not carry.

Traits signalling Dene arrival

Southwest archaeological traces should signal Dene arrival. New or mis-identified sites can be examined using Chipewyan traits:

- Concealed camps in foreign territory or game overlooks;

- Over-represented worked flake clusters with few finished tools;

- Plains Side-Notched arrowheads for bow hunting and raiding;

- Sinew-backed bow held horizontally which might appear in pictographs;

- Sandstone disc or cobble spall chithos, plus troughlike bone beamers for removing hair and metapodial fleshers for removing fat and flesh;

- Levelled sleeping or task spaces ringed by stone. Tent rings may be absent when sand was kicked onto tent flaps;

- C-shaped, 3-rock-lined hearths opening east;

- Skin-lined earth depressions with fire-cracked boiling stones may be analogous to Apachean roasting pits;

- Dominant west wind may result in tools more NE or SE of hearths to avoid smoke and cinders;

- Bone from mid-sized dogs used for transport; and

- Dead buried in remote brush-covered rock crevices.