Photographing nearby sites for possible future analysis and dating was ongoing. They include: (a) the Hummingbird site near Pemberton, BC, my visit a courtesy of Johnny Jones, Mt. Currie 1st Nations Cultural Technician, whose photo shows decade-old weathering effects compared with 2009 (Photos 1 & 2); (b) Betty and Ralph Hagenbuch’s Pateros site 45OK34 near the confluence of the Methow and Columbia Rivers in north-central Washington, where I compared a 1930 drawing with what remain today (Photos 3 & 4); (c) a complex, partly destroyed site a few km east of Tonasket and near Anglin hamlet, marked “Indian Writing” on Washington State maps (Photo 5); and (d) EbRk-1, a pictograph on a 15cm deep, dirt-covered ledge several hundred meters downstream from the Main Pictograph wall EbRk-2 in the Stein Valley (Photo 6).

Pictographs with photographed and sampled soil levels are: (a) boulder sites 45OK392 and 45OK603 (courtesy Gadd and Boreson) in the south-flowing Chewuch tributary of the Methow River, itself a south-flowing branch of the Columbia River (Photos 7 & 8); and (b) the Main Pictograph wall EbRk-2 in the Stein Valley. 45OK392 had been vandalized, likely by high school students celebrating their graduating year, and has since been restored. Underlying the bottommost motifs on its wall were new growth shrubs and a layer of Ponderosa pine needles from nearby trees (Photo 9). Removing the needles revealed an ash layer from a recent forest fire (Photos 10 & 11). We set up our camera and tripod (Photo 12) to begin our 20x50cm soil “slot” vertically under the densest art motifs by simply dropping a pebble. This placement enhanced our chances of photographically locating coloured pigment particles. We further improved our chances by sampling the surface of each level using our glue-paper technique at 45OK603 (No Snake) site.

Abundant charcoal for AMS dating was screened from many 5mm (1/4”) scrapings in the underlying soil levels down to 30cm using a 8-10” stainless kitchen sieve (Photo 13). The site surface was then restored to its original appearance (Photo 14). We also took 5-10 minute-exposure infrared photos (Photo 15) to see if we could penetrate lichen blocking half of a motif. If successful, this would allow pictographs to be seen without destroying the lichen and rendering the art more susceptible to weathering. 45OK392 was also used to test our grid layout for accurately identifying small motifs within large composites on rocks walls using stadia rods (Photo 16). Particle assessment using high resolution photography (38 MB jpgs) and collection for pigment identification, in this case red ochre, are ongoing.

We ran two simultaneous adjacent tests at another pictograph called No Snake further up the Chewuch River (Photo 17). This site was excavated in 1993, with former crew Betty and Ralph Hagenbuch returning to help after 16 years (Photo 18). Using 1993 photos and plans, we placed our narrow test slots between their excavation and the boulder. The technique works best (30-50 5mm peels daily) with three people. The pace-setter is the scraping person (Photo 19), who places a small paper with level number on the surface of each ‘peel’, manually focussing his camera lens on the number, photographing the level, and then scraping 5mm of soil into a dustpan. A second person sifts the soil, collecting datable charcoal and non-cultural carbonaceous material for dating (needles, wood & bone frags.), plus cultural items like flakes. These are ‘bagged’ in aluminum foil, along with the level number paper not in contact with material. After noting a new level, plus relevant data like site designation, compass bearing, etc., consistently in the same corner, a third person places a thin layer of water-soluble glue (e.g. Elmer’s) on an approx. 8.5″x11″ area in the middle of an 8.5″x14″ legal copy paper (Photo 20) and hands it by its ends to the scraping person (Photo 21). That person places it across the ‘peel’ surface and pats it throughout, before lifting it and turning it over to dry before the next paper. At the end of work, the stacked paper is turned over to resume its correct order and the site surface is restored to its original state. The stacked paper is shipped to the lab in a cardboard box tightly packed to counter particle dislodgment.

In the Stein Valley at EbRk-2 (Photo 22), I chose the best area for testing, based on: (1) the most extensive art or thick palimpsest paint; (2) soil depth tested with a survey pin; and (3) relatively rock-free areas which eases scraping. One red ochre particle was actually identified at the site on a glue-paper by John Haugen, Lytton 1st Nations Councillor and a Board member for Stein Valley Nlakápamux Heritage Park.

Future fieldwork plans involve investigating the sites mentioned in the opening paragraph, using these techniques and others that may be developed.

Offsite Analysis of the peel images and their corresponding level samples has so far produced these Results. On the following page, I discuss earlier evaluations by rockart analysts, and consider the potential for particle dating in this region.

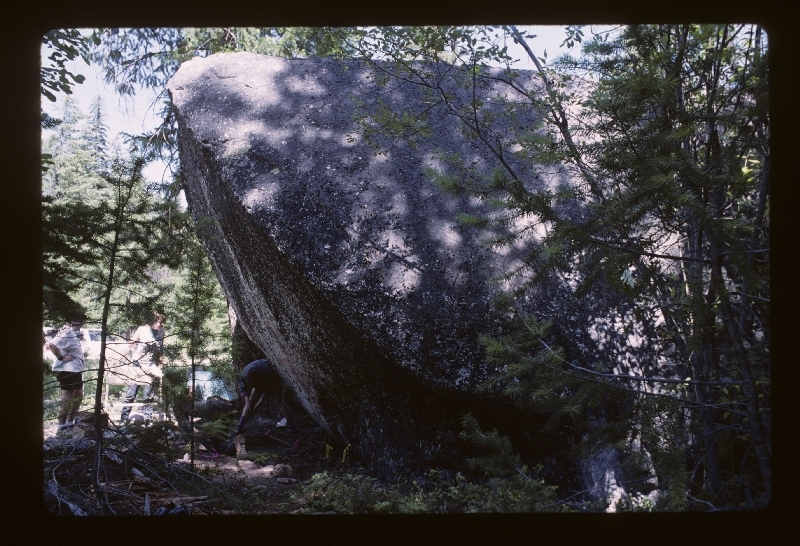

Site 45OK603 or No Snake Creek Pictograph is near Winthrop on the Chewuch branch of the south-flowing Methow tributary of the Columbia River in eastern Washington State (Boreson 1994). Its southwest-facing red pictographs, covering a 2.7 by 2.4 m area, are on a large boulder, and include rayed arcs, an anthropomorph and two vertical undulating snakes? These resemble motifs in southern British Columbia, expanding Keyser’s conclusion of a “remarkably homogeneous group of paintings and carvings scattered across a broad region of many thousand square miles” (Keyser 1992:57). Excavated material near the rock face and down to 20 cm subsurface, with most at 5-10 cm, included charcoal (undated) and bone fragments, flakes (one worn), a point tip, fire-cracked rock and a small granite river cobble battered at one end and stained with red ochre. Watchman (1993) examined a small wall art fragment using SEM, finding parallel lines suggestive of brush marks. As many motifs are being invaded by Rhizocarpon geographicum, an attempt at lichen dating was proposed but abandoned. Similarly, the point tip was not time-diagnostic and the charcoal undated. The anthropomorph may not be what it appears, relating instead to “gender-specific tasks conducted by adolescent girls during seclusion and training” (Boreson 1994:28).

Our 2009 fieldwork added data. The shallow material excavated many years ago correspond to peel 2 in the table which has many tiny red particles at 10 mm subsurface. Regarding the anthropomorph, James Teit (1900), married to an Interior Salish wife, mentioned a humanlike stick figure actually represented a girl enclosed in spruce branches as part of her puberty rite. There was also a lizard and horned figure, while one bird atop and one below our motif photo strongly resemble Teit’s photo of a Shakan Eagle on a pictograph boulder near Nicola, southern British Columbia (see website under Nicola field reports). Our nearby Ten Mile Woman pictograph had no datable charcoal because its underlying sand was windblown, while The Shakan Eagle boulder had been transported 5-7 km from its original stance. Beta Analytic Inc. (#268144) dated abundant charcoal in 45OK603 from level 18 at 90 mm subsurface to 1600±40 BP (conventional age 1630±40 BP), with a 13C/12C ratio of -23.2, a, and 2 sigma calibration of 340-540 AD (Cal BP 1610-1410). No other Winthrop area pictographs have been dated by any method, although 45OK392 was tested without finding red particles in its jpgs, and its glue sheets have yet to be studied. The 45OK82 boulder motif was above sloping pebbly windblown sand and was not tested. Watchman (1993) studied a cross-section of a pigment-coated chip, revealing solution-transported <5 micron diameter angular amorphous silica under the pigment paint, with none above, suggesting to him that the art is relatively recent.

Regarding ochre origin, Post and Commons (1938:69) mentioned “mineral paints were obtained from a place in Canada”. My 2007 fieldwork near Princeton, British Columbia, included a visit to an immense red and yellow ochre source used by ancient artists throughout the Interior Plateau and its pigment was carried to the pictographs we studied at Hedley and Nicola, and likely to the Stein Valley, Mt. Currie and the Winthrop sites.

References:

Boreson, Keo 1994. Documentation of Pictographs at sites 45OK82, 45OK392, and 45OK603, Okanagan National Forest, Washington. Ms. prepared for Okanagan National Forest (March).

Keyser, James D. 1992. Indian Rock Art of the Columbia Plateau. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Post, R.H. and Commons, R.S. 1938. Material Culture. IN The Sinkaietk of Southern Okanagan (L. Spier, ed.). General Series in Anthropology 6, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM.

Teit, James 1900. The Thompson Indians. American Museum of Natural History, Memoir 2(4), Publications of the Jessup North Pacific Expedition 1(4):163-392.

Watchman, Alan 1993. Methow Valley and Winthrop pigments, Washington. Data-Roche Watchman Inc., Quebec, Canada.