International Response to the Expulsion

by Olivia Musselwhite

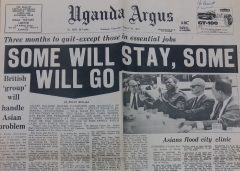

On August 4th, 1972, General Idi Amin announced the expulsion of the South Asian community in Uganda. Reactions immediately spread across newspapers, asking the question of where the community would go.

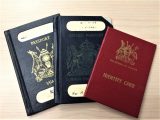

The answer to where the Ugandan Asian refugees would resettle started with their citizenship statuses at the time. Of those Ugandan Asians who did not have Ugandan passports or were currently waiting to obtain one, the majority of Ugandan Asians held British citizenship, followed by Indian, Kenyan, and Pakistani passports (Muhammedi, 2017). At first, the expulsion included those without Ugandan citizenship, but eventually the order spread to the entire Ugandan Asian community with little exception (Muhammedi, 2017). Ugandan Asian families could no longer stay in the country, leaving their futures in the hands of other governments.

After Amin’s expulsion announcement, Britain sent Minster Geoffrey Rippon to East Africa in an attempt to sway Amin’s decision, but the expulsion could not be stopped or delayed (Mahoney 2022). On August 11th, Britain declared that it would take responsibility for the Asians in Uganda that held British passports (Mahoney 2022). On August 14th, a headline in The London Times read, ‘we accept our responsibilities’.

Ugandan and British passports and identity cards. Archives & Special Collections, Carleton University

The same day, The Globe and Mail reported that the first twitches of fear from cities were emerging, unwilling to take more than a few hundred refugees (McCullough, August 14, 1972). The idea of an influx of immigrants was met by both positive and negative feedback from the press. Some papers were opposed to increased numbers of refugees, printing vicious cartoons and reporting the disapproval of the general public (McCullough, 1972). Others supported the intake of refugees, reporting that in the long run the Ugandan Asian community would be an asset to Britain (“Is Amin trying to blackmail Britain?”).

For India, many British Asians were applying at the Indian High Commission to obtain visas (“Must give up U.K. citizenship”). The Indian government was only accepting British passport holders who were willing to renounce their British citizenship and become Indian citizens. (“Must give up U.K. citizenship”). The British government argued that since many of the Ugandan Asians held Indian passports, that they should join Britain in convincing Amin to extend the deadline, and that immigrants with U.K. passports should be able to go to the country of their choice due to cultural, language, and family reasons (“U.K. calls on Canada”).

Due to the high number of Ugandan Asian refugees who needed a permanent place to live, Britain called on the world to provide aid. On August 19th, the British government requested that Canada, New Zealand, and Australia take some of the refugees (“U.K. calls on Canada”). Canada’s response to the request came from a Canadian High Commission spokesperson who said that, “The request is an additional element in the serious consideration being given to the problem by the Canadian government” (Mahoney, 2022). On August 24, Prime Minister Trudeau announced Canada’s decision to “offer an honorable place in Canadian life” for refugees. (Mahoney, 2022). Canada’s first major resettlement of non-European ref

ugees was of the Ugandan Asians, with nearly 8,000 accepted between 1972 and 1974 (“Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada”).

The same openness to refugees was not shared by the rest of North America. At the end of August, the United States announced that they would speed up their application processes, but they were not creating an emergency program to accept large numbers of refugees (Mahoney 2022). In October, it was announced that the United States would accept 1,000 refugees on a parole basis, so long as refugees had no valid citizenship and had professional capabilities (Mahoney 2022).

By the end of October, the United Nations was permitted by Uganda to organize travel documents for those who were without any citizenship (Mahoney, 2022). The Inter-governmental committee for European Migration then arranged transportation to countries including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, Malta and Spain (Mahoney, 2022).

For the Ugandan Asian refugees, their forced migration created a sense of homelessness and a sense of loss as they rebuilt their lives in new places (Herbert, 2012). Alongside this loss was the development of transnational affiliations, creating rich and complex identities and a new sense of the meaning of ‘home’ (Herbert 2012). The Ugandan Asian community spread across the world, building new futures for themselves and for future generations.

References

Herbert, J. (2012). The British Ugandan Asian diaspora: multiple and contested belongings. Global Networks, 12(3), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00353.x

Is Amin trying to blackmail Britain? (1972, August 15). The Globe and Mail, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/.

Mahoney, J. (2022). Chronology. The Uganda Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/chronology/.

McCullough, C. (1972, August 14) . U.K. Officials study ways to head off sudden influx of Asians from Uganda. The Globe and Mail, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/.

McCullough, C. (1972, August 19). U.K. calls on Canada to admit Asians expelled by Uganda. The Globe and mail, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/.

Muhammedi, S. (2017). ‘Gifts From Amin’: The Resettlement, Integration, and Identities of Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4438.

Must give up U.K. citizenship: 15,000 Asians to go to India. (1972, August 18). Ottawa Journal, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/.

The Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada. The Uganda Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/background-idi-amin-uganda-1972/.