An Overview of the South Asian Expulsion in Uganda and Canada’s Response

By Jackie Mahoney

The circumstances that brought about the expulsion of the South Asian population from Uganda began evolving when, in 1894, Uganda became a protectorate of the British empire. As the British came to power, the demographic of Uganda started changing as South Asians from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and other countries also under British rule were brought to Uganda as indentured labourers to construct the Uganda Railway. They also began coming to Uganda as traders, establishing shops that sold small amounts of exotic consumer goods in exchange for equal amounts of surplus produce from farmers (Jamal, 1976). As the railway became operational, it allowed the British access to Uganda’s resources that included tea, coffee, sugar and cotton (Bennion, 2002). Subsequently, as trade developed in the country, the British increasingly relied on the Asian population to facilitate their operations and expand their colonial rule. This preference was influenced by Britain’s racist sentiments towards African Ugandans and the fact that there were thousands of South Asians, particularly from India, who, because of Britain’s preestablished rule in India, spoke English, had received an English education, and were already working as colonial administrators before they immigrated. This translated into the Asian population of Uganda gradually becoming entrenched as the business elite in the country (Bennion, 2002). Not all Ugandan Asians may have experienced this privilege, but by the time that Uganda gained independence in 1962 they constituted a small part of the population but earned a significant percentage of the national income. This added to increased tensions between African and Asian Ugandans that were further exacerbated when Milton Obote became president in 1966. Obote pursued what he called the “Africanization” of Uganda, which involved restricting the involvement of non-citizen Asians in the economy in an attempt to better insert African Ugandans into positions of economic importance (Saul, 1976). Obote’s government created a number of political crises for the country but did include Ugandans of both African and Asian descent (“Background: Idi Amin’s Uganda, 1972”).

While attending the Commonwealth Conference in Singapore in 1971, Obote’s government was overthrown by General Idi Amin, the commander of Uganda’s armed forces, who subsequently took over as president. Amin took the “Indophobia” that Obote had planted the seeds of and made it much more widespread and damaging (Patel, 1976). In 1971, Amin ordered a review of citizenship status for Uganda’s Asians as well as a census of the Asian population living in Uganda (Jørgenson, 1981).

The Expulsion Announcement

Even still, on August 4, 1972, there was a great deal of disbelief when Amin announced, “the decision of his government asking the British Government to take over responsibility of British citizens of Asian origin living in Uganda who were ‘sabotaging the economy of the country’ and were practicing and encouraging corruption” (Mukasa, 1972). With this announcement came a great deal of confusion and incredulity. The British government immediately began trying to encourage Amin to go back on what he had said or change his mind in some way. They met with little success. Once it was widely understood that Amin had no intention of changing his mind, Britain had to make hasty arrangements for the approximately 50 000 Asians holding British passports in Uganda. The situation was made worse when, on August 9, Amin announced that the expulsion also included citizens of Bangladesh, Pakistan and India who were living in Uganda (Mukasa, 1972). India had already announced that it would only accept a limited number of British passport holders of Indian origin if Britain acknowledged that they were their responsibility (“15 000 Asians to go to India,” 1972). The expulsion was further escalated when, on August 11, Amin announced that all Asians with Ugandan passports had have their citizenships checked for accuracy. Many were told that their citizenship papers were faulty. Around 10 000 Ugandan Asians became stateless because of this and found themselves added to the numbers that had to quickly find ways out of Uganda (St. Vincent, 2005).

Britain announced that they would ultimately accept responsibility for their citizens but knowing that an influx of 50 000 or more refugees would be nearly impossible to accommodate in the UK, they asked other commonwealth countries to open their doors to the fleeing Ugandan Asians. Having already acknowledged that Canada should assist with the situation in Uganda on humanitarian grounds, within five days of Britain’s request, Canada took steps to establish an emergency admissions program with initial estimates of accepting 5000 refugees (St. Vincent, 2005).

Canada’s Response

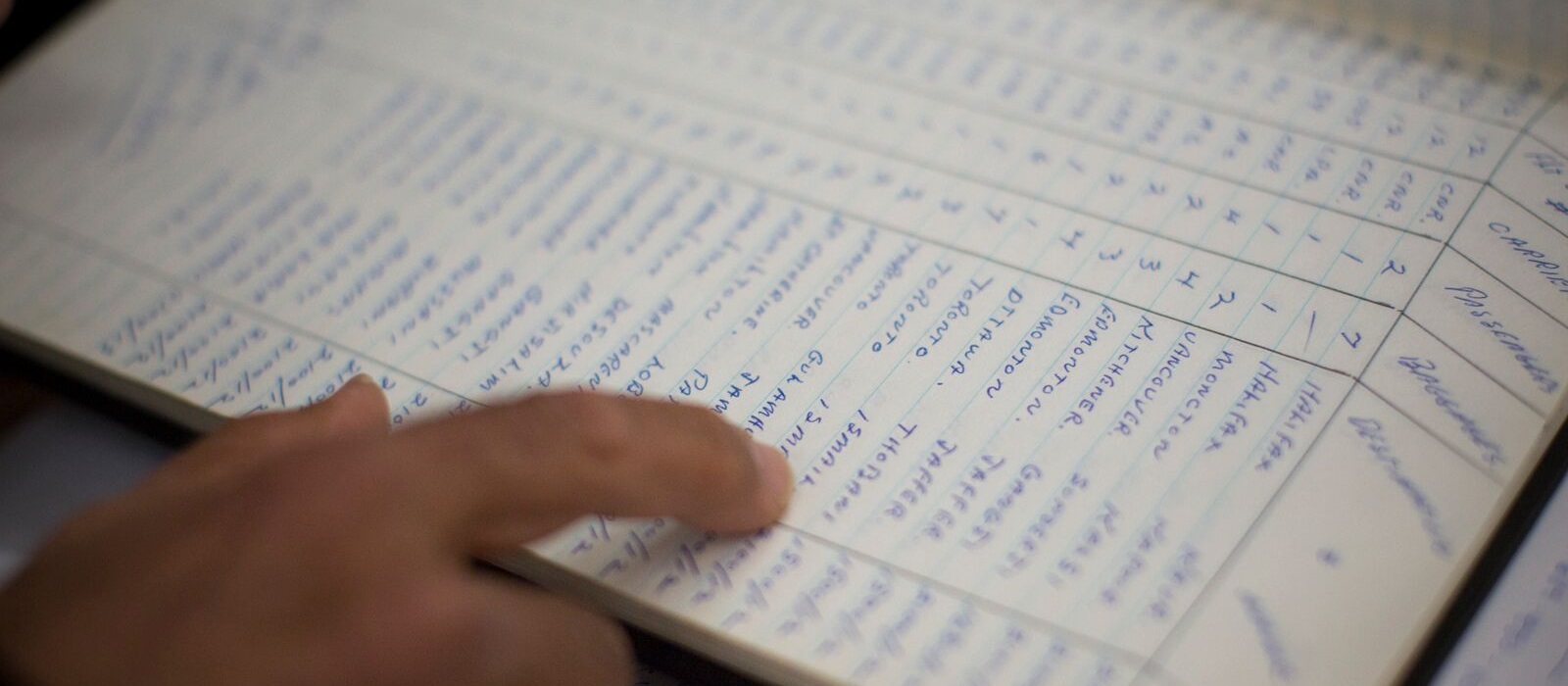

As the situation in Uganda became more dire, however, Canada decided to accept Ugandan Asian refugees, “without numerical limitation” (St. Vincent, 2005). As officials from Canada were rushing to set up the immigration office in Kampala at the beginning of September, Amin specified that the Asian citizens would have to depart by November 8, or else they would be, “rounded up by military forces and put into camps” (“Uganda Asians Facing Threat of Internment,” 1972). With this horrifying fate on the horizon, Asian Ugandans were eager to leave the country as quickly as possible. Those looking to go to Canada were delayed by the late arrival of the medical unit, but upon their arrival on September 16, they quickly made up for lost time. Having been forced to leave behind nearly all their belongings, abandon their homes and businesses, and carrying just one 20kg bag per passenger, the first charter flight to Montreal from Entebbe left on September 27 (St. Vincent, 2005). By October 18 there were daily (and sometimes twice daily) chartered flights to Canada. Once arrived, the Ugandan Asian refugees would be taken to CFB Longue-Pointe, which had been converted to receive and house them until more permanent arrangements could be made. With the assistance of Ugandan Asian Committees, refugees made their new homes in communities like Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Vancouver, Victoria, Edmonton, Regina, Winnipeg, Hamilton, Halifax, and Windsor.

In the end, around 27 000 refugees immigrated to the UK, nearly 7000 arrived in Canada, and 4500 went to India. Other countries that accepted refugees in smaller numbers were Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Malawi, Pakistan, Kenya, Austria, Sweden, and Norway (Jorgensen, 1981). The Asians who were previously Ugandan citizens that had been made stateless by Amin were taken care of by the United Nations and sent to refugee camps in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. (UNHCR, 2000) In the wake of the Asian expulsion, Uganda’s economy suffered immensely, causing inflation to soar. There were not enough trained people remaining in Uganda to take up all the positions (doctors, teachers, business owners) that became vacant when the Asians left. There were massive food and supply shortages, and the agricultural production centres were subsequently abandoned, or they were reduced to subsistence farming (Bennion, 2002). It would take another decade and the presidency returning to Milton Obote in 1982 for Uganda to begin to return the land that had been owned by Ugandan Asians. In 1986, President Yoweri Museveni condemned Amin’s actions and invited the Asians who had been expelled to return (Dawood, 2016). However, the deep impact of the expulsion has continued to be felt in Uganda and around the world by those forced to flee and those who worked to admit them.

Chronologies

Uganda Timeline

This timeline centres on how the expulsion unfolded in Uganda. It demonstrates the historic circumstances the expulsion evolved from and how it developed and changed over time. The timeline also reveals how President Idi Amin’s sudden changes to who the expulsion applied to negatively impacted Asian citizens and how quickly they had to flee. The varying responses of countries like Britain, India, the United States and Canada reveals a great deal about the political climate at the time.

Canada Timeline

This timeline focuses on Canada’s response to the expulsion and how the country facilitated the immigration of over 7000 Ugandan Asian refugees in under 90 days. It explores how key individuals involved in the effort like Roger St. Vincent and Michael J. Molloy adapted their tactics as they dealt with the changes to and evolution of the expulsion as the deadline approached. As the Ugandan Asian refugees began to settle in Canada, the timeline notes Canadians’ reactions to the newcomers and how they were welcomed into a number of Canadian communities.

References

15 000 to go to India: Must Give Up UK Citizenship. (August 18, 1972) The Ottawa Journal, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/

Background: Idi Amin’s Uganda, 1972. The Uganda Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/background-idi-amin-uganda-1972/

Bennion, J. (2002) Asians in Uganda. PBS Frontline World: Roughcut. https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/rough/2007/05/uganda_the_retulinks.html

Darwood, F. (2016, May 15) Ugandan Asians Dominate Economy After Exile. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36132151

Jamal, V. (1976). Asians in Uganda, 1880-1972: Inequality and Expulsion. The Economic History Review, 29(4), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/2595346

Mukasa, W. (1972, August 10) Some Will Stay, Some Will Go. The Uganda Argus. The Bennett Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/the-bennett-collection-uganda-argus-newspaper/

Patel, H. H. (1972). General Amin and the Indian Exodus from Uganda. Issue: A Journal of Opinion, 2(4), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166488

Saul, J. S. (1976). The Unsteady State: Uganda, Obote and General Amin. Review of African Political Economy, 5, 12–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3997806

Saint-Vincent, R. (2005) A Very Fortunate Life. Unpublished Manuscript courtesy of the Uganda Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University.

The State of the World’s Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action. (2000, January 1) The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/sowr/4a4c754a9/state-worlds-refugees-2000-fifty-years-humanitarian-action.html

Uganda Asians Facing Threat of Internment. (1972, September 9) The Vancouver Sun, courtesy of the Hempel Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Carleton University. https://carleton.ca/uganda-collection/archival-material/the-hempel-collection-looking-in-from-the-outside/