Light and Shadow Over France

by Alexander Zoubek – Collections Assistant 2025 (Practicum Student)

Pierre du Prey’s photographs of France not only document the country’s storied architecture, but also capture the more elusive qualities of light and shadow upon its many historic sites, whose appearance changes with the time of day. Working through multiple cross country treks that stretch back to the late 50’s, his Kodachrome slides convey a methodical, ambulating journey wherein du Prey’s lens mirrors the role of the sun, both revealing and eclipsing the landscape before his gaze. The seven photos that I have selected can be considered emblematic of both a multi-layered French heritage and the artistic qualities of the photographic medium, which are often glossed over in such documentary work.

Just outside the commune of Ayette lies a graveyard honouring the Chinese and Indian labour corps of the British army (as well as Chinese labourers in the French army), which served on the Western Front during the First World War. Many of the Ayette labourers came from Southern China, and their tombstones include various translated inscriptions such as ‘A Good Reputation Endures Forever.’ [Fawcett, 58]

Such cemeteries can be found across northern France and around the Belgian border, where trench warfare necessitated a variety of backbreaking labour – ranging from digging, filling sandbags, and tending to railways. Many of their tombstones date from after the signing of the armistice in 1918, with the continued death owing to the unenviable duty of digging up explosives. [Fawcett, 45] Du Preys’ photo conveys both peace and stability. Dappled with shade, the central mausoleum is flanked by two trees that hold up the top frame of the image like twin columns. The grave stones are a luminous white, seeming to glow against the azure-blue sky akin to marble, porcelain, or perhaps bone.

Les Espaces d’Abraxas (or “Spaces of Abraxas”) is a peculiar work of postmodern architecture by Ricardo Bofill, resembling a cross between a Greco-Roman theatre, a temple, and a dystopian office building. Built between 1978 and 1982, The Spaces were made to serve as a state-subsidized housing project amidst overcrowding in Paris. Dominating the suburban skyline, Bofill’s top-down approach reveals the contradictions of leftist, late-modern architecture: while he sought to “ennoble the lives of his working class tenants and cooperative owners,” his rigid and impractical design reflects a desire to shape their everyday lives akin to a benevolent dictator. [Schuman, 26] The massive and monotonous scale paired with the empty surroundings creates an oppressive atmosphere, one that is only further enhanced by recalling Imperial Rome. The use of the complex as a backdrop for the dystopian sci-fi film Brazil a mere three years after its construction all but confirms Bofill’s architectural vision lies closer to Stalin than Marx.

The selection of this architecture for photography fits within du Prey’s affinity for utopian neoclassical architecture. While he made sure to photograph the grand and occasionally grotesque geometries of the complex, he also brought out the oddities of its more “mundane” details. This uncanny photo of one of the alleyways is a high-relief carving of light and darkness, where the architecture seems to advance and recede simultaneously. The cube-shaped capital appears to be suspended in midair, and the shadows underlining the wall further suggest that the structure is slowly rising upwards, defying gravity through sheer ambition (and perhaps a touch of arrogance).

Mont-Dauphin is a remote commune in the Haut-Alpes department, near the Swiss border. Occupying an alpine plateau, the town’s heavy fortifications were part of a chain of fortresses built and/or restored by the Maquis de Vauban, who served as marshal of France under Louis XIV. Now recognised as a UNESCO world heritage site, Vauban’s fortifications have demarcated the largely-unchanged French border, and nowadays serve as tourist attractions. [Johnston, 176] Mont-Dauphin is no exception, though the town appears deserted in du Prey’s photograph.

Aside from capturing the walls and motes of Vauban’s fortress, du Prey took the time to document the commune itself. Its nearly identical rows of plaster houses are both quaint and unnervingly empty, with the wide street leading our eyes to the clocktower and the snow-capped mountains beyond. The time appears to be 10:50 am, yet the street is still bathed in shadow. If a lamppost were to be included, the scene would resemble Magritte’s The Empire of Light.

Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye was commissioned by Pierre and Eugénie Savoye, and was built between 1928-1931. Though functionally a house, its form took precedence over function – most notably in the case of its roof, whose omission of gutters and water spouts made it prone to water damage and leaking. As a result, its distinctive modernist design saw it become a historic monument, with its significance lying in the aesthetic presentation of the architect’s “Five Points of a New Architecture.” [Murphy, 75] In other words, it was a house that the architect built for himself and was content with not living in.

In this rare interior of the master bathroom, du Prey reveals the oft-overlooked effect of his skylights upon a living occupant – a young boy washing his hands. The sublime form of the light upon the tile wall renders our protagonist a silhouette, with the sharp angle of the sunbeam directing our eyes to a pull-cord switch. The mysterious doorway that lies beyond is scarcely darker than the foreground, where the child’s doppelganger reclines beside the recessed bathtub.

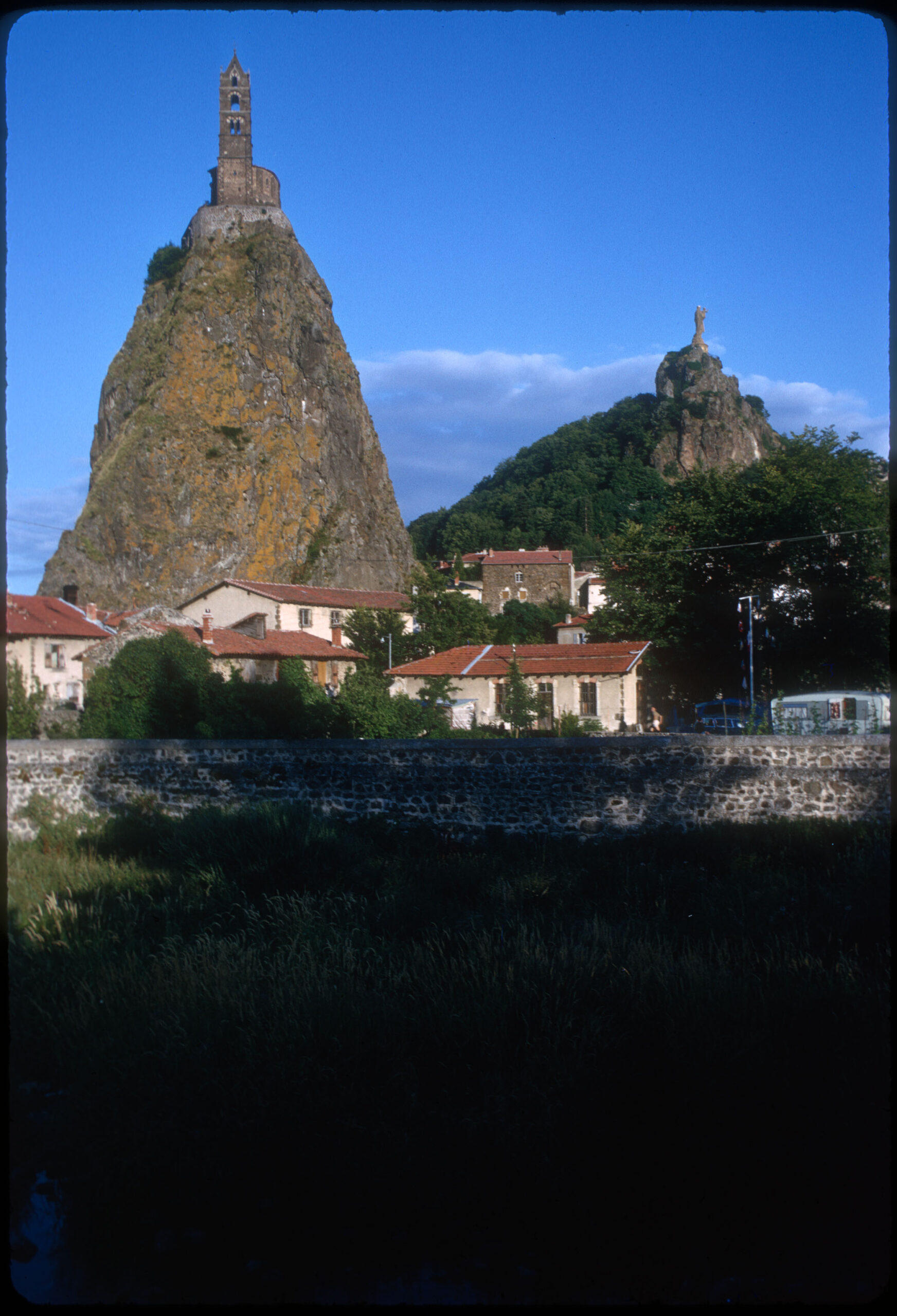

Not all monasteries can boast occupying the crest of a half-formed volcano (technically a volcanic plug), and fewer still have 236 steps carved directly out of the igneous rock. In fact, the dedication of this Romanesque skyscraper to Saint Michael –the patron saint of mountains– most likely owes to this geographic feature. Since its founding in 951 by Bishop Godescalc, the chapel has looked down over the surrounding commune, though its belltower would not be added until the following century. From under the shade of a nearby tree, we can see both the monastery over Le Puy-en-Velay and the distant statue of the Virgin Mary, each rising up atop their respective crests of rock.

Du Prey had taken over a dozen photos of it, all from different angles to show its preeminence, but I chose this one for the sheer scale it presents. The darkness of the ground only emphasizes the apparent benevolence of the two religious structures, which stand a silent vigil over the red tiled roofs below. It is easy to imagine the building as a stand-in for God Himself, and the psychological effect of its presence above the townspeople begets further speculation.

Built in 1846, Tours Station follows the Beaux-Arts design of local architect Victor Laloux. The two enthroned figures pictured above are allegories of Bordeaux and Toulouse, carved from limestone and made to resemble Roman patron goddesses. Holding dominion over space (the railway) and time (the clock), they seem to suggest the imperial reach of the July Monarchy, which was still in the process of conquering Pōmare IV’s Tahiti (and would be overthrown by the short-lived Second French Empire two years after the station’s construction).

Here, du Prey once again shows his appreciation for classical architecture by focusing on the station’s clock as it’s squeezed between two monumental Doric columns, whose oppressive forms are dressed up in slightly pompous baroque ornamentation.

And yet there is a peculiar harmony between these elements and the blocky, modern text that wraps around the column bases like labels on a coke bottle. As a result, the slightly tyrannical presentation of Bordeaux and Toulouse speak less of some sublime nationalist power but rather inordinate amounts of money. The latent passage of time indicated by the clock is reinforced by the rising shadow of sunset.

Circling back to another WWI monument, The Canadian National Vimy Memorial commemorates the first battle in which all four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force led a coordinated attack against Germany, sacrificing 3600 men and wounding thousands more as part of the British-led Battle of Arras. The monument was designed in 1921 by the Canadian sculptor Walter Seymor Allward, who had designed another monument commemorating the Second Boer War in 1910 (where the use of concentration camps somewhat dampens any myth of heroic nation building.) Despite its symbolic importance for nascent Canadian nationalism, the memorial was left untouched by the Nazis, which may have been owed to the “predominant mood (…) of mourning and grief” that it presents. [Hucker, 99]

This photograph displays the double-lifesize sculptures that flank the structure. Craning their necks to stare at the sky, their luminous bodies appear rather uncanny against the background of the empty park, which resembles the homescreen of an old Microsoft desktop. The obscured staircase provides an unusual view of the site, which remains silent in its sun-drenched emptiness.

Bibliography

Fawcett, Brian C. “The Chinese Labour Corps in France 1917-1921.” Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 40 (2000): 33–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23895259.

Hucker, Jacqueline. “‘Battle and Burial’: Recapturing the Cultural Meaning of Canada’s National Memorial on Vimy Ridge.” The Public Historian 31, no. 1 (2009): 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2009.31.1.89.

Johnston, A. J. B. “Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban: Reflections on His Fame, His Fortifications, and His Influence.” French Colonial History 3 (2003): 175–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41938241.

Murphy, Kevin D. “The Villa Savoye and the Modernist Historic Monument.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 61, no. 1 (2002): 68–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/991812.

Schuman, Tony. “Utopia Spurned: Ricardo Bofill and the French Ideal City Tradition.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 40, no. 1 (1986): 20–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1424844.