In Conversation with 2024-2025 Munro Beattie Lecturer Ann-Marie MacDonald

By Maya Chorney

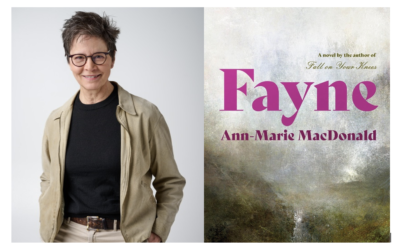

Portrait by Travis Silverman; Front Cover of Ann-Marie MacDonald’s 2022 Novel Fayne

In advance of the annual Munro Beattie Lecture on February 4, acclaimed author, actor, and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald sat down with English student Maya Chorney to discuss her multidisciplinary career, the power of storytelling, and the political dimensions of her work. This conversation offers a glimpse into the themes she will explore in her upcoming lecture, Imps and Imposters: Where Do Stories Come From?, at the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre.

Maya Chorney, (M.A. Candidate, Department of English)

Maya: Your career started out in theatre. You trained at the National Theatre School of Canada, you’ve performed for the stage and the screen, and you have also authored and co-authored several plays.

How has your theatre background influenced the trajectory of your writing career? And how did those early experiences in writing for the stage inform how you would later approach novel writing?

Ann-Marie: My theatre background gave rise to my fiction writing, quite literally, because I set out to write a play which then became Fall on Your Knees. I was simply acknowledging that the story wanted to be born into a different kind of body. It didn’t want to arrive in the world as a play, it wanted to arrive as a novel, and I followed that. Then it became a play again in a wonderful kind of evolution where it returned to its genesis.

Acting also informed my writing for theatre because I always write from the point of view of performance: How is this going to be experienced on stage by the actors, the director, the designers, and the audience? Always writing with those many dimensions in mind. When I wrote Goodnight Desdemona, it was the first play I wrote that I knew I was not going to be in. That freed me up to really pay attention to the parental metaphor “all my children.” I realized, oh, I’m going to take equal responsibility for every single character arc as well as for how they all come together in the overarching plot. And that was a hugely important step. All my writing is informed by my experience of embodying story as an actor. And in turn, my writing for theatre has informed my fiction writing because I’m always trying to create a three-dimensional, immersive experience for the reader.

Maya: On the topic of being a multidisciplinary artist, I’ve always been interested in having what we might call a “slash career,” and learning about how other people make this kind of career work for them. You know, not limiting yourself to being just one thing for your whole life.

Can you tell me more about that willingness to remain fluid and follow your curiosity? What advice would you give to young writers who want to maintain their craft alongside other pursuits?

Ann-Marie: That adaptability is more important than ever now. And I certainly grew up with that. I grew up with a mother who really believed that you have to use all of your talents, pursue all of your gifts. My father, too, was a great proponent of changing careers. It was a different time and place, because you could do that more safely in the mid to late twentieth century. Things are more precarious now than they were then, which of course means that, in turn, you need to be ready to be adaptable more than ever. That readiness is more important than ever.

I’ve never heard anyone use the term “slash career,” but it really resonates. I’ve been an actor for stage, television, and film, a playwright, a screenwriter, a broadcast host, a novel writer…I’ve never seen them as being essentially different. They’ve always been different ways of doing one thing, which is telling stories.

From my perspective now, I have a lot of compassion for people who are in your cohort, your generation. You are highly educated, extremely aware, and living in a more precarious world than the one in which I came of age. There’s always precarity, there’s always some kind of threat, there’s always challenge. The world is never a Garden of Eden. But there is an intensification. There’s a gigification of work. And I think, “wow, that’s really hard.” I like to honour the younger generation by saying I respect your challenges—they’re serious. And I don’t think anyone does much without the help of the older generation. We’re all in this together.

Maya: I’d like to dwell in the realm of the political a bit longer. In an interview with McGill, you described how binaries have been a dominant concern for your entire career. You went on to say that your most recent novel, Fayne, “is the ultimate challenge to any binary notion, whether it is of our body, our sexuality, our gender, or the nature of reality and our world itself, and the discovery of what is truly valuable.” As a queer feminist storyteller and scholar, what really stands out to me in your work is how you write marginalized narratives back into the literary record. Fayne is a clear recent example of this, but it’s also prevalent in earlier work like Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet), which doesn’t so much queer Shakespeare as it plays with the gender fluidity already inherent in the Bard’s productions.

Can you share a bit more about your thoughts on literature as a platform for writing about those historically marginalized narratives, or of the relationship between art and politics more broadly?

Ann-Marie: I love to play with established and traditional forms. With Fayne, I use the gothic novel, the Victorian novel, full of tropes and devices and conventions and conceits which are completely delightful and familiar. They’re deeply familiar. Even anyone who’s never read a Victorian novel has watched a Netflix series set in the late nineteenth century, on a moor or in a mansion, set somewhere in the United Kingdom. We are familiar with these conventions. I feel like I’ve done that with most of my work, where I’m going to play with a familiar form, I’m going to enjoy that form, I’m going to offer the delights of that form to the reader or the audience member. And it’s going to allow me to take the audience or a reader on a journey they might not otherwise take and engage with and identify with people they might normally think of as being very other or repellent or frightening or just wrong.

And so, hopefully I’ve made the invitation welcoming and gracious enough that people go “sure, I’m coming with you.” And then by the time they’re surrounded by people they would never ordinarily even say “hello” to, it’s too late. They’re having a cup of tea with them, or they’re going on a mortal quest with them. They’re aligned, they’re identified, they’re seeing through somebody else’s lens, somebody else’s point of view. Point of view is everything. That’s it really. I’ve never been the kind of artist who needs to assault the reader or the audience, to prove how important it is that you listen to me and how wrong you are. I’d rather invite you. I think the kind of change that is possible when you actually invite people is much more radical and profound and long lasting.

Maya: So, a gentle invitation to be more open.

Ann-Marie: Yes, and I think that is radical and profound and has longevity. I think it makes lasting, deep change.

Maya: Now, of course, you’ve written plenty of historical fiction.

Do you write as you research? How do you know when to stop thinking and researching, and when to start writing?

Ann-Marie: I think the process is not just in tandem—back and forth—but one process bleeds into the other. So, the edges of research becoming writing are blurred, as with everything. And that’s where the richness lies, in that uncertainty, that blurriness, in that “actually, I’ve absorbed enough of that to go off into that new blank page.” So, there’s a lot of overlap. It’s almost as if you’re on a rowboat and you’re crossing a body of water. And then you feel that you’re contacting the seabed, there’s sand on the keel. And then you say to yourself, “okay, I’ve run aground, I need to deepen things again. I need to learn something again.” So I go back to the research, and then my boat is freed up again.

Maya: Where do you get your inspiration from, these days?

Ann-Marie: I never know until it’s already happened. Kind of like “oh, well that’s where that came from!” Right now, I’m working on a one-woman show. I’m drawing inspiration from my own life experience in a very open, direct way. But because it’s going to be embodied in movement and sound and performance, there’s a funny kind of thing. Because I’m working on a one-person show for myself to perform, I’m willing to be very personal in the material that I use, directly autobiographical in a way that I never am when I’m writing fiction or theatre. And I think the reason I’m doing that is that I know I’m going to be embodying it, performing it—it’s going to be me and the audience in real time. And for some reason, that feels less exposing than were I to sit down and write a memoir, the idea of which every fibre of my being is allergic to. But I’ll perform a memoir!

Research is very important. There are a lot of things which I intuit. And as I get older I have more and more material. More and more experience. I may have lived something or feel I have a strong intuitive grasp of something, which tells me that I’m capable of getting something right on the inside of it, but it also tells me not to take for granted that I have all the information that I need. To me, that is always an indication that I have a lot of learning to do. I’m always wanting to put something that I may understand intuitively into a larger context. And I want to get it right, because I think it does not make itself. I need to learn a whole lot so that I have a grasp of a subject so that the characters can have maybe a faulty grasp or a contradictory grasp. But I know the whole picture.

Maya: Kind of learning the rules so you can break them, even if it’s through the characters.

Ann-Marie: Exactly. I think that’s also part of the trust that is necessary between writer and reader. I take that trust very seriously.

Maya: To finish up, are there any books, plays, or films you have enjoyed recently?

Ann-Marie: I just saw a play at Crow’s Theatre here in Toronto. It’s called Dinner with the Duchess and it’s by Nick Green. The writing and the acting and the production were absolutely a tour de force. There are probably no more than five shows I have ever seen in my lifetime where I would use that descriptor. It was absolutely great. I loved it.

Most of the books I read are non-fiction. There’s a book that I read fairly recently, which I absolutely loved. It’s called The Utopia of Rules. It’s all about the rise of bureaucracy. It’s by an author named David Graeber, who is unfortunately deceased. He died during Covid at quite a young age. But it’s a book that says a lot about our world.

Maya: I feel that a book about bureaucracy would definitely go over well with an Ottawa audience.

Ann-Marie: Right? Absolutely. It’s a book about bureaucracy and it’s a page turner—which sounds like a joke, but it really is! It’s funny and it’s incredibly smart.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Office of the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and the Department of English Language and Literature invite you to join us for the 2024-2025 Munro Beattie Lecture, “Imps and Imposters: Where Do Stories Come From”, with author, actor, and playwright, Ann-Marie MacDonald. It will take place at 7:30 pm on February 4 at the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre.