An Interactive and Experiential Approach to Teaching Religion

The Introduction to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam course held by Religion in the College of the Humanities has long been a staple as a very popular choice for undergraduate students from all areas of study at Carleton University.

The course provides students with an objective historical and modern critical understanding of these three Abrahamic religions and is designed to foster skills such as critical thinking, self-reflection, appreciating nuance, and understanding the sweep of history.

Although these skills remain as vital and applicable as ever, post-secondary schools in Ontario face new pressures to demonstrate how their student programming translates to larger economic impact across the province. In light of these new provincial government priorities, Professor Kim Stratton took a novel approach to teaching Judaism, Christianity, and Islam over the 2019 summer session.

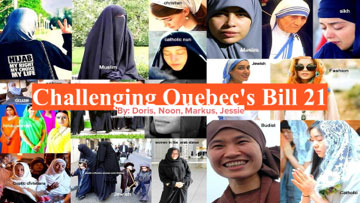

Rather than having students submit a research paper and write an exam, those who took the course were assigned interactive and experiential exercises that challenged them to apply their acquired knowledge to realistic work-place and societal situations. These exercises included hypothetical challenges to improve Religious literacy in Canada by writing a Religious Accommodations Policy for an imagined company, creating a strategy for a campaigning Canadian political party that appeals to all three religious communities, and having students create a mock impact statement for a Human Rights organization that is challenging Quebec’s newly passed anti-religious-symbol law (Bill 21). While Professor Zeba Crook is currently teaching this course during the fall and winter terms in the traditional, and historically very successful model, Stratton will employ similar experiential learning activities in RELI 3722 – Religion and Violence – which she is teaching in January 2020.

Professor Stratton discussed her reconfigured summer course and new ways of teaching with the FASS Newsletter and also spoke at length about the monumental value of the study of the humanities towards nurturing outstanding citizens and a healthier society.

[button title=”Experiential Education at Carleton ” url=”https://carleton.ca/experientialeducation/” style=”red-solid” class=”center” /]

Professor Stratton, could you please unpack the decision to change the format of The Introduction to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam course?

The provincial government’s new budget changes priorities for secondary education by emphasizing employability skills and experiential learning over and above all other academic measures of achievement; following release of the bill in April, I wondered how those priorities might be met in the context of Religious studies. Courses in Arts and Social Sciences almost universally inculcate skills like writing, critical thinking, and reading, which enhance an applicant’s employability and, as research indicates, improve an employee’s upward mobility over time. But these skills remain vague and ill defined, especially for students who might not actually know what sorts of tasks are involved in many or most jobs they are likely to have in the course of their lives.

I wanted to incorporate, therefore, exercises that simulate real-life job-based situations in which Religious Literacy might be required. Many people do not automatically think of knowledge about religion as a job skill. So, I framed the course with the intention of imparting this idea. Of course, part and parcel of acquiring Religious Literacy is the development of critical thinking skills, especially, the ability to talk about religion in an unbiased, non-theological, academic way. This poses a challenge for many people who are used to thinking academically in other contexts, like engineering, biochemistry, or history.

The problem for a course like this is how to inculcate an understanding of religious history, beliefs and practices that leaves God at the door and contemplates these aspects of human society without pre-judgement or recourse to insider (theological) discourse.

Religion is everywhere in the news lately, mostly negatively … There is a growing contingent of Trump supporters who identify him with the “anointed” figure mentioned in Isaiah 45, and expect him to usher in Armageddon. All these cases point to the presence of Religion in public life.

How, in your opinion, is the University model evolving?

There is a lot of pressure lately on universities to find private sources of funding by making alliances with corporations. As governments in Canada and abroad seek to lower expenditures, education, especially secondary education, finds itself compelled to adopt a corporate model, which measures worth of research programs, academic disciplines, and individual academics in economic terms. The days of intellectual exploration merely for the purpose of expanding one’s knowledge of self, of humanity, and of the universe–are in the past. Students, their families, and the government increasingly regard university as primarily a jobs training institution although originally, and historically, this was never the intention of a university education. Less than a century ago, a university degree was considered elite. It was expensive, reserved for the upper classes, and helped differentiate those who governed society, from laborers, who used their bodies, not minds, to earn their daily bread. Reading “useless” things like Shakespeare or Plato was not intended to get one a job, but to educate one on the profound contradictions of human existence, the vicissitudes of history, and beauty of art, love, and learning. From there, one was in a better position to lead society as a more informed, thoughtful, and engaged citizen of the world. When we focus on job training in a very limited way, we transform higher education from a place where the human mind is supposed to be challenged, nourished, and expanded, to one where it is treated like a machine, whose primary purpose is performing useful tasks. In this course, I am trying to create a bridge between these two views of university education by showing how exploring and understanding the deepest desires, fears, and joys of the human spirit, as expressed through religion, can also serve a useful purpose in the job sector.

What do you hope your students walked away with after taking this course in its new format?

I hope that students walked away from this course with a better knowledge of all three monotheistic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), beginning with their complex, interconnected and often fraught histories. This knowledge also enables them to understand the beliefs, doctrines, and practices of these religions as they evolved out of specific historical periods, were shaped by specific historical people, and responded to specific historical events. The course continues to emphasize an unbiased, objective and academic study of Religion, which is well reflected in the new text book that my colleague, Zeba Crook, just published.

Professor Crook wrote the textbook specifically to teach this course, and it challenges students to engage with the difference between theology and a historical critical approach to thinking about religion. I also hope that through this course and learning this approach students can be more understanding and tolerant when encountering members of different religions or hearing stories about other religions in the news. A lot of violence and suffering could be avoided if more people were religiously literate. This means, not just knowing details about religions different from one’s own, but as importantly, being able to view one’s own religion with critical distance, objectivity, and dispassion.

Why, in contemporary times, do you believe the study of religion is particularly important?

Religion is everywhere in the news lately, mostly negatively: in the past 12 months an Islamophobic white supremacist gunned down 51 innocent men, women and even children at two mosques in Christchurch NZ; anti-Semitic attacks killed 12 Jews at two Synagogues in the United States; in early 2017, a Canadian man walked into a Mosque in Quebec City and murdered 6 men at prayer. There is a growing contingent of Trump supporters who identify him with the “anointed” figure mentioned in Isaiah 45, and expect him to usher in Armageddon. All these cases point to the presence of Religion in public life.

Yet, I would argue that it is not Religion, but ignorance about Religion that is most prevalent and responsible for religiously incited violence. Stereotypes of Islam and Muslims as violent, sexist, and oppressive proliferate in the media, perpetuating false ideas about the religion and spurring fear and hatred of its adherents. Anti-Semitism has a long and tragic history yet continues to rear its dangerous head by perpetuating well-worn tropes about Jews trying to take control of the world through financial and political networks. Misinformed readings of biblical texts perpetuate fantasies about an eschatological war and return of Jesus. These ideas are specious but influential. Ignorance contributes to intolerance on all sides of the culture wars. If our goal is a free and open society based on equality, concord, and justice, then knowledge about the Other is of the utmost importance. In fact, it is essential given the globalist reality that we currently inhabit. Religious Literacy can serve as an antidote to the fear that rapid social change often inspires as it destabilizes traditional, segregated ways of living.

Could you speak about the student’s work assignment options for this course?

The final group-projects were the most exciting for me and the place in the course where I engaged most directly with the challenge to inculcate “employability skills.” Students were asked to choose from 5 real-world scenarios where knowledge of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam would be necessary to solve real-life problems.

I asked the students to form groups of 4-5 people, ideally from different religions in order to benefit from a variety of perspectives at the discussion table. Students were asked to apply the knowledge they gained from the course in particular scenarios, which allowed them to deepen their learning as well as to engage with perspectives different from their own in a problem-solving context. In addition to the specific skills they acquired through their experiential learning projects (e.g., writing a curriculum, devising a company policy), they had the opportunity to develop general employability skills such as leadership, teamwork, and public speaking. I strove to offer scenarios that would appeal to and benefit students from a variety of disciplines and with different career objectives.

The first option asked students to design a curriculum to improve Religious Literacy and fight religious intolerance in Canada. This assignment required students to understand what a curriculum is and how it functions by considering questions such as what grade level they plan to target, what activities, exercises, and assessments they plan to include.

The second option invited students to pretend that they work in the Human Resources office of a large company that employs Jews, Christians, and Muslims. They needed to write a Religious Accommodations Policy for the company that fairly addresses the different needs of religious individuals while keeping an eye on the bottom line. I specified that in addition to the obvious requirements of observant Jews and Muslims they needed to take into consideration minority Christian groups, such as Orthodox Christians or Seventh Day Adventists, as well. The third option asked students to imagine that they are Religious Consultants for a Canadian political party who wants to attract voters from the three religious communities represented in the course—i.e., Jews, Christians, and Muslims. They needed to write a plan for this party that helps it appeal to the values, concerns, and needs of all three religious communities, without alienating any of them. The fourth option and, arguably, the most challenging asked students to resolve the Israeli/Palestinian conflict so that it is fair to all sides and takes the specific needs, desires, and histories of the different groups into consideration. For this exercise I asked that they consider several objectives, including the need for security and safety, access to sites of religious and historical importance, freedom of movement, reunification of families, fair and equal treatment before the law, recognition and respect for each group’s distinct history, values, and needs. They were also asked to avoid displacing people as much as possible. The fifth option required students to pretend that they work for a Human Rights organization that is challenging Quebec’s newly passed anti-religious-symbol law (Bill 21). They were asked to write an impact statement that represents all three religions and bases their response on history, scripture, beliefs and practices rather than on emotion or opinion. The projects were evaluated on the degree to which they demonstrated knowledge of all three religions and reflected learning covered in the course. Furthermore, they needed to present material in an objective and academic manner, which avoids biases and arguments based on opinion or theology. In other words, they needed to demonstrate a clear understanding of the academic study of religion in contrast to the theological or faith-based claims of religious insiders.

Interestingly, what emerged from all the presentations was the degree to which Religious Literacy of the type I am trying to inculcate was a primary solution to the various problems the groups were addressing. I did not anticipate that conclusion, but it certainly reinforces not only the importance and relevance of courses in Religious Studies, but of enlisting experiential learning in some of those courses to draw out the real-world implications, applicability, and importance of Religious Literacy.

Professor Stratton is currently writing a book, From Babylon to Exodus: Violence, Story, and the Origins of Judaism and Christianity, that draws on insights from trauma studies and anthropology to explain the rupture between Jewish sects in response to the failed revolts against Rome (66-70CE and 132-135CE). While other scholars have largely focused on identity formation or Christology as primary reasons for the separation of Christianity, Stratton takes a different approach, one that considers the need to restore coherence and hope in the face of failed expectations for divine redemption. The parting of the ways between Judaism and Christianity, Stratton proposes, was precipitated, or at least exacerbated, by finger-pointing and laying blame for the catastrophic Roman-Judaeo wars. She hopes to complete the book by the end of 2020.