By Lilly Neang, Rachel McNally, and Nadeea Rahim

Original version published 25 March 2020. Revised version published 12 May 2022.

Introduction

In 2019, the editors of the journal Migration Studies embarked on a self-reflection process about the geography of submissions to the journal, resulting in a blog post asking the critical question: Does the gap in migration research between high-income countries and the rest of the world matter? They concluded that the “vast majority of migration research seems to be originating in high-income countries.” Inspired by this blog post and the reality that today 86% of the world’s refugees are hosted in the global South, LERRN began to investigate the authorship and content of some of the most recognized academic journals in the field of refugee and forced migration studies. LERRN published the original version of this analysis of the Journal of Refugee Studies in March 2020. Since then, LERRN has published an analysis of Refugee Survey Quarterly and an analysis of Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees. LERRN also hosted a webinar involving the editors of these two journals to reflect on the results of the analyses and questions of access and representation in academic publishing. In 2021, the Journal of Refugee Studies stated its desire “to work towards further diversifying the journal in terms of themes and approaches, as well as in terms of attracting more publications by emerging researchers and scholars from the Global South.” As academic journals in the field of forced migration studies consider various initiatives to reduce barriers for authors based in the global South and authors with lived experience of displacement, we hope that these analyses can continue to inform the conversation.

In the spirit of continuing this conversation, this blog post presents a revised version of LERRN’s analysis of the Journal of Refugee Studies, considering the geographic focus and authorship of the published articles and book reviews. Compared to the original version, it broadens the scope to include the 305 articles and 141 book reviews that were published over the 10-year period between 2010 and 2019 (the same time period as LERRN’s Refugee Survey Quarterly analysis). The Journal of Refugee Studies celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2018 and is arguably the leading journal in the field. The journal is clearly aware of some of the issues surrounding global imbalances in knowledge production, publishing several related articles in the last decade.[1] There have also been several changes at the journal since 2019 when the time period of this analysis ends, including a new editorial team in 2021. The Book Reviews section of the journal was replaced in 2021 with a broader and more inclusive Reviews section that welcomes reviews of other material in addition to academic books (such as autobiographies and creative literature), texts published in any language, and historical texts.

Methodology

Using the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD) classification of countries (“developed regions” as global North and “developing regions” as global South), we analyze global North and global South participation through categorizing the articles based on the authors’ institutional affiliations at the time of publication and the countries where these institutions are located. A limitation of this approach is that it relies on the information about authors that is published along with the articles/book reviews and does not consider other forms of geographic identification, such as nationality data or connections to the region, which were not available for this research. Instead, this analysis considers the question of whether scholars from the global South require either a co-author from the global North or an institutional affiliation in the global North to be published in some of the most-cited journals in the field. The North/South classification is a vast simplification that obscures significant differences within these categories, but it is a useful shorthand to examine questions of geographic representation and to represent some of the dynamics involved in the political economy of knowledge production (such as access to research funding). For the book reviews, authorship refers to the person who wrote the review, not the author(s) of the book. This analysis only considers the articles and book reviews that were selected for publication, so the results may be different looking at all the articles and book reviews submitted to the journal. However, this information was not available to the researchers. All the refugee and displaced persons population figures in the rest of this blog post come from UNHCR’s 2019 Global Trends report and reflect the numbers of forcibly displaced persons at the end of 2019 (in line with the time period of the analysis). Within this time period, the number of forcibly displaced people worldwide nearly doubled: from 41.1 million at the end of 2010 to 79.5 million at the end of 2019.

Results

Global South vs. Global North Authorship

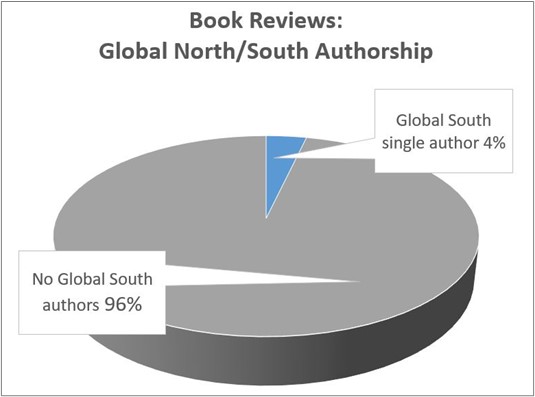

As countries in the global South host the majority of refugees and other displaced persons, it is important to consider the representation of global South voices in the academic literature on forced migration. Of the 305 articles, 15 (5%) were written by single author based in the global South and an additional 26 (9%) included global South authors through co-authorship (Figure 1). A similar trend was noted in book reviews, with only 5 (4%) of the 141 reviews written by global South authors (Figure 2).

Collaboration and Co-Authorship

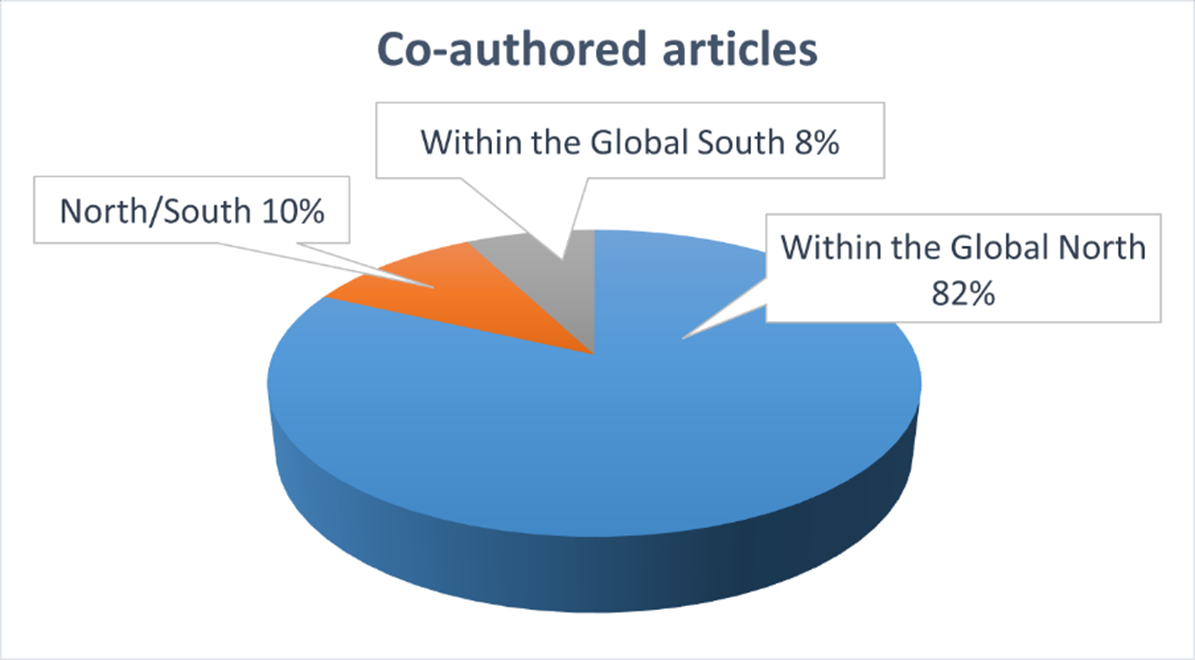

Nearly half of the articles (47%) in the Journal of Refugee Studies are co-authored, where collaboration between different countries is common. Although these partnerships are primarily between authors based in the global North, 15 (10%) articles involve North-South partnerships, and 11 (8%) of co-authored articles only include authors based in the global South (Figure 3).

Authors by Country

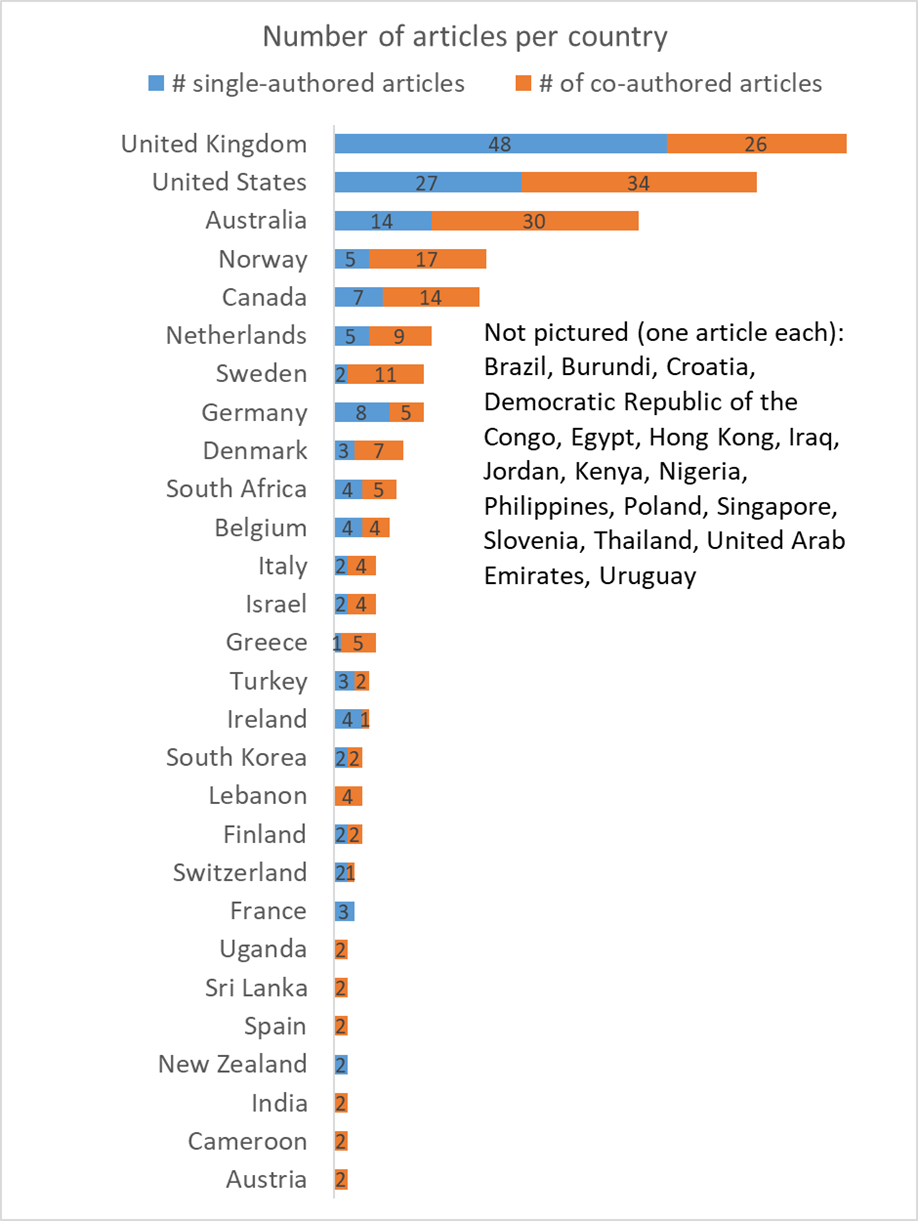

The JRS authors are based in many different countries. In the articles, 45 different countries were represented, including 23 countries in the global North and 22 countries in the global South. However, 17 of these 45 countries only have one article each. In addition, authors based in countries in the global South produced less articles per country overall, with an average of two articles per country, compared to an average of 14 articles per country for countries in the global North. These statistics are nearly identical for book reviews, with averages of 1.1 articles per country in the global South and 13 articles per country in the global North.

Authors based in the United Kingdom lead with the most publications, as 74 (24%) articles and 73 (52%) book reviews include at least one author based in the UK (Figure 4). All of the top 10 countries for both articles and book reviews are in the global North. However, countries are not necessarily directly comparable because of vastly different populations, economies, and size of the postsecondary sector or number of scholars studying forced displacement. Considering some of these differences, another way to look at the data is to consider articles by country population. When the figures are adjusted to the number of articles per capita, the top 10 are still all from the global North, but there are slight changes in which countries lead in publications. In this case, Norway has substantially more articles than any other country with 41 articles per 10 million people. However, the book reviews show a different pattern, as Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, both countries located in the global South, make it in the top 10 for book reviews per capita.

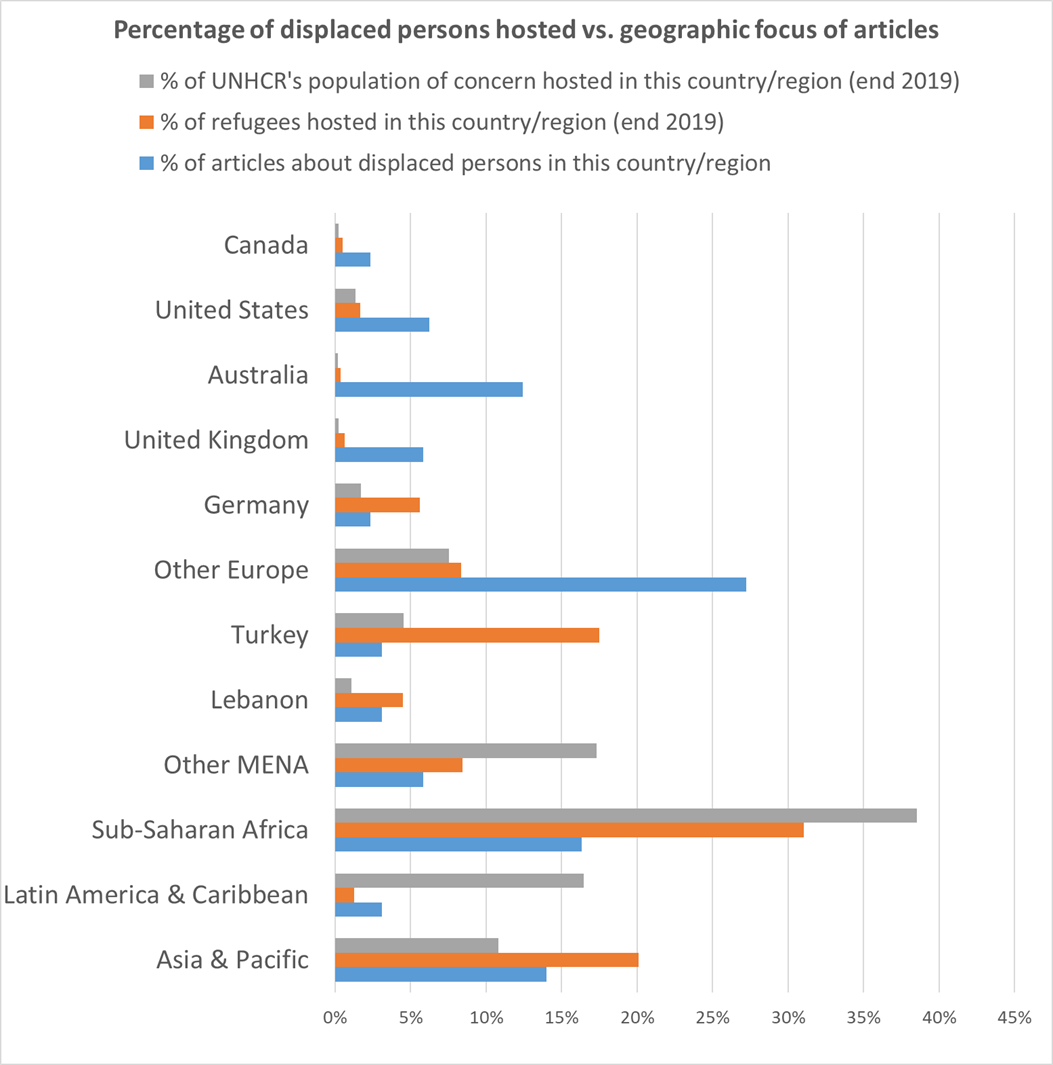

Geographic Focus

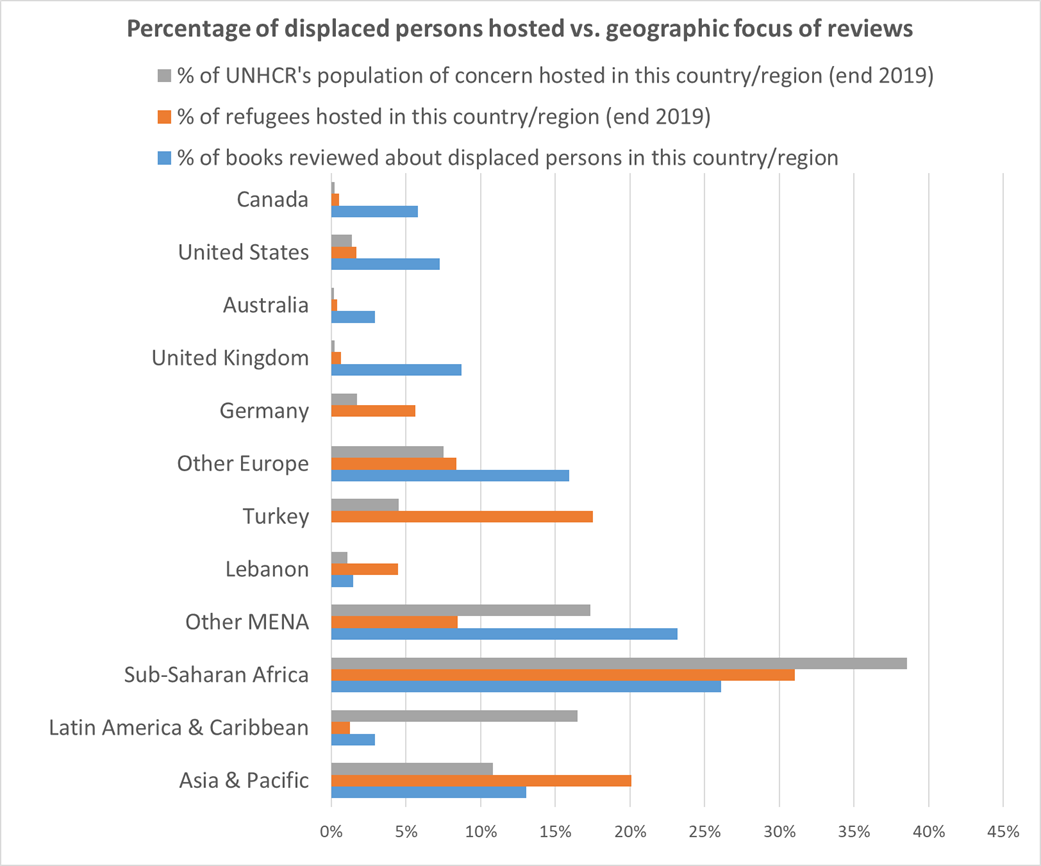

The articles published cover issues related to forced migrants hosted in every region of the world. However, refugees and other forced migrants are distributed unevenly around the world. Despite hosting a lower percentage of the world’s refugees and forced migrants, some countries and regions are the focus of a high percentage of the articles published in JRS. Of the 305 articles, 48 (16%) focus on globally relevant topics such as international refugee law, forced migration history, and multilateral humanitarianism. The remaining 257 were then sorted into 12 different country/regional categories. Australia, Canada, the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe (excluding Germany) are over-represented as the geographic focus in the journal. Collectively, these countries in the global North hosted only 12% of the world’s refugee population at the end of 2019 but more than half (54%) of the articles focus on displaced persons in these countries. In contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa hosted 31% of the world’s refugees and 39% of UNHCR’s population of concern at the end of 2019, but only 42 (16%) of the articles discussed forced migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 5).

Among the book reviews, 72 (51%) do not have a country/regional focus and discuss global topics such as climate-related migration. The book reviews that do focus on a particular country or region generally show similar patterns to the articles, with one major exception. Unlike the journal’s articles, the Middle East and North Africa region (excluding Turkey and Lebanon) is also overrepresented in addition to those previously mentioned from the global North (Figure 6).

Type of Displacement

Each article and book review was coded according to the group or groups of forced migrants it discussed: refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons (IDPs), stateless persons, or “other” to capture groups of (forced) migrants who fall outside UNHCR’s population of concern. For both articles and book reviews, refugees were the primary focus, with 182 (60%) articles and 75 (53%) book reviews talking specifically about refugees. Since the founding of the Journal of Refugee Studies, the field of refugee studies has expanded to consider forced migration more broadly and to consider the experiences of those people who may not have the legal status of ‘refugee’. Asylum seekers or asylum systems were discussed in 43 (14%) articles and 16 (11%) book reviews. It is recognized as a gap in the field that scholars have paid limited attention to Internally Displaced Persons. This gap is reflected in the journal, as only 19 (6%) articles and 3 (2%) book reviews discuss Internally Displaced Persons. Very few articles or book reviews (less than 1%) discussed issues related to stateless persons.

Public Accessibility

JRS is a subscription-based journal. Among the articles published from 2010 to 2019, access to nearly all of them (98%) is restricted. Only 5 of the 305 (2%) articles are open to the public. Since the time period of the analysis, there has been an increasing number of articles published open access or available for free (14 articles in 2020 and 33 articles in 2021).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Like LERRN’s previous analyses of other journals in the field, the results show a significant imbalance between where refugees and other displaced persons are located versus where journal authors are located. There is a similar imbalance in the geographic focus of the articles and book reviews, which more often discuss the much smaller number of refugees and asylum seekers who have reached the global North. In the broader international context, these results reflect structural imbalances in access to refugee-related research funding, an issue that has been discussed in the journal and in a recent LERRN webinar. There are also some unique challenges for refugee researchers in certain countries, such as a political context that makes it difficult to criticize government policy.

This analysis lends further support to ongoing conversations at forced migration journals about ways to reduce barriers for potential authors based in the global South and authors with lived experience of displacement. Journals in the field may consider initiatives such as mentorship programs offering one-on-one support to potential authors, writing workshops for potential authors, and additional editing or other supports within the publication process. Other initiatives beyond the journals, such as direct funding for local institutions and researchers, may also be helpful in addressing some of these barriers.

Given the very limited number of articles that are available to the public without a subscription, JRS could consider increasing open access content to make its articles more accessible for readers, particularly those readers from practitioner communities, people with displacement experience, or readers in the Global South who do not have access to institutional journal subscriptions. As noted above, in the last two years many more articles have been available open access than during the time period of the analysis.

The new approach to the Reviews section of the journal, as mentioned above and detailed on the journal website, aims to diversify both what gets reviewed and who writes reviews. However, as the Review Editor also notes, writing a review is primarily a service to the field overall. It may not be fair to expect academics in the global South or people with a lived experience of displacement to do the time-consuming work of writing reviews without compensation and with limited benefit to their own careers. In this context, the JRS Review Editor has suggested that established scholars based in the global North can play an important role in writing reviews that bring attention to the work of refugees and of scholars in the global South.

For over 30 years, the Journal of Refugee Studies has published high-quality research on issues related to forced displacement and has made a significant contribution to the development of the field of refugee and forced migration studies. Going forward, the journal can play an equally significant role in facilitating a truly global academic conversation and in publishing articles and reviews that together show a representative picture of forced displacement around the world.

[1] Including “Communities of Knowledge or Tyrannies of Partnership: Reflections on North–South Research Networks and the Dual Imperative” by Loren Landau (2012), “Beyond the Partnership Debate: Localizing Knowledge Production in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies” by Richa Shivakoti and James Milner (2021), and “Carving Out Space for Equitable Collaborative Research in Protracted Displacement” by Maha Shuayb and Cathrine Brun (2021).