With many colours and hues represented, all clustered unworked flakes, broken knives and core fragments of the same material and hue were interpreted as coming from the same knapping station via one core and a hammerstone of unrelated hue and material (hammerstones appear in other activities). Finished knives would have been removed for use elsewhere, while broken unused scrapers were absent. First, we grouped flakes, broken knives and core fragments in relation to their hue, removing beige artifacts from the palimpsest, then brown (Figure 5), gray (Figure 6) and orange (Figure 7). Pink, beige and pink, beige and gray, white, beige and green, and beige and orange-banded artifacts were also plotted but undepicted due to publishing constraints. Other colours were too rare to consider. For clarity, human icons were added to graphs based on the activity represented. Shoulder widths of men (45 cm) and women (35 cm) are to scale. Icon orientation was based on artifact distribution, space needed for the activity and handedness (10-20% left-handed).

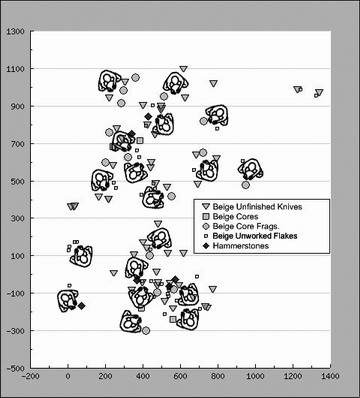

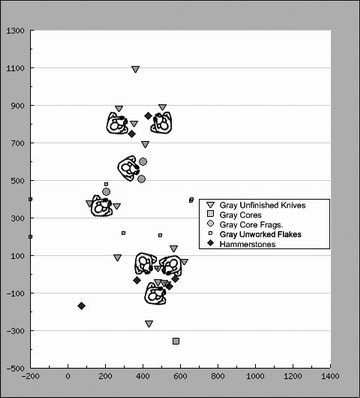

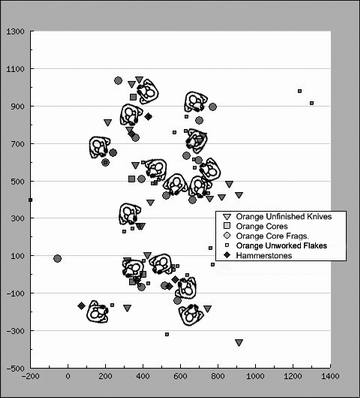

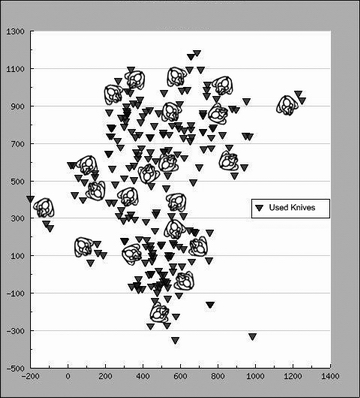

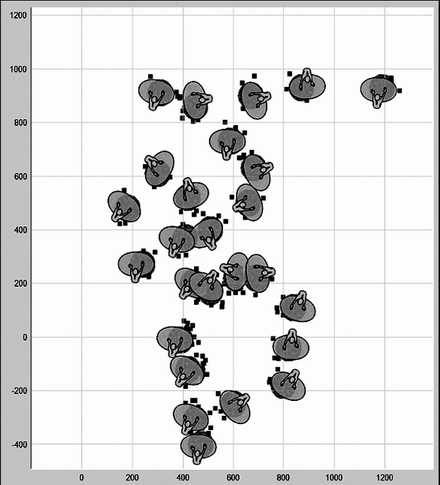

Assuming some artifact clustering remained after 400 years of use, we first plotted knapping activity (Figure 4). Preparing dozens of knives for butchering Rangifer was the first major activity while awaiting herd arrival. With many colours and hues represented, all clustered unworked flakes, broken knives and core fragments of the same material and hue were interpreted as coming from the same knapping station via one core and a hammerstone of unrelated hue and material (hammerstones appear in other activities). Finished knives would have been removed for use elsewhere, while broken unused scrapers were absent. First, we grouped flakes, broken knives and core fragments in relation to their hue, removing beige artifacts from the palimpsest, then brown (Figure 5), gray (Figure 6) and orange (Figure 7). Pink, beige and pink, beige and gray, white, beige and green, and beige and orange-banded artifacts were also plotted but undepicted due to publishing constraints. Other colours were too rare to consider. For clarity, human icons were added to graphs based on the activity represented. Shoulder widths of men (45 cm) and women (35 cm) are to scale. Icon orientation was based on artifact distribution, space needed for the activity and handedness (10-20% left-handed).

Figure 4. Beige quartzite knapping stations |

Figure 5. Brown quartzite knapping stations |

Figure 6. Grey quartzite knapping stations |

Figure 7. Orange quartzite knapping stations |

This technique may seem inapplicable to Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic archaeologists

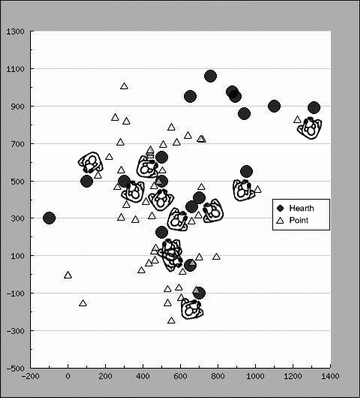

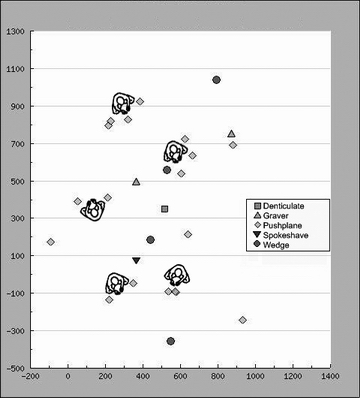

Figure 8. Middle phase lance production stations

analyzing flint blades, blade-like knives and scrapers, and points and cores of the same colour, but do not despair. It is only one of seven techniques we used, colour being unimportant in the remaining six.

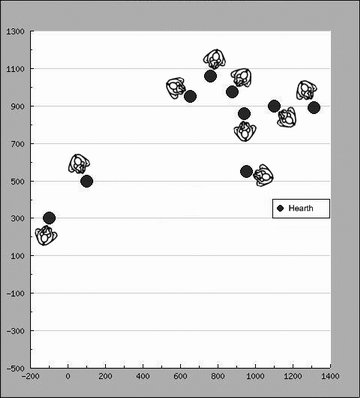

The second major activity was lancing Rangifercrossing the river (Figure 8). Although wood is unpreserved, a quartzite spokeshave may have been used to round lance shafts. Three edge grinders were used to dull lance or point bases to protect hafting sinew from being cut. Ten complete lance heads with ground bases were ready for hafting. A followup more intense activity was lance head or point repair (Figure 9). Loosening broken lance heads from their shafts involved water and heat to liquify the blood glue from the sinew binding. That is why we find 49 lance head bases in or near hearths. The six hearths to the north (top) were confined to grease extraction and roasting meat (to follow).

For the third activity (Figure 10), we plotted butchering stations, involving the use of worn knives, where women cut meat from each quarter for thin slicing and wind-drying, setting aside long bone for later fragmenting. Twenty-one icons of women were oriented according to clustered worn knives. They likely cut and piled the strips on a partial or full hide, perhaps a meter or so in diameter so that others, perhaps their daughters, could wind-dry it on willows or suspended rawhide rope. Each icon required a minimum of several knives in an arc of 60-120º from the centre of the hide and many more could be added in both dense central areas.

Figure 9. Middle phase lance repair stations |

Figure 10. Middle phase butchering stations |

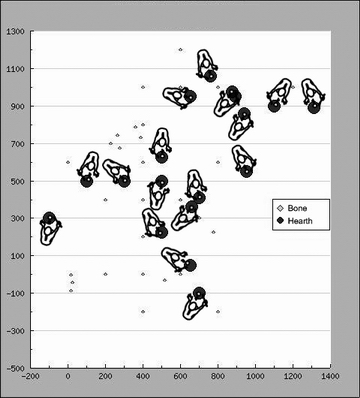

The fourth activity (Figure 11) is hearth-centred and involved roasting of non-marrow bones to cook adhering meat and brain for immediate consumption. Here, nine hearths contain non-marrow calcined cranial, rib, vertebral, and distal leg and ankle bones.

Figure 11. Middle phase meat roasting stations

In the fifth activity the residual long bones from butchering were smashed with a hammerstone, exposing marrow for later grease extraction using boiling water flotation (Figure 12). This involved a hammerstone, hearth, fire-cracked rock, uncalcined long bone fragments and space for a birchbark boiling vessel or a rawhide-lined ground depression filled with water. Here, 17 women with forked sticks for relaying hot rocks from hearth to water for boiling were placed according to handedness. Right-handed women extracting grease would have the fire on their left and transfer rocks and broken long bones to a pool on their right. Left-handed women were placed on the assumption that the fire would be to their right and rocks and broken long bones would therefore be transferred to a pool on their left. By adding rocks until the water boiled, they skimmed the floating grease off its surface to a skin or bark container. It was later mixed with dried meat powder as pemmican and stored. When the pool filled with extracted bone and fire-cracked rock, both were thrown further right or left according to handedness, and where we excavated them. The boiling water was rarely east of the hearth because the dominant west wind (from left) would cover it with ash and cinders. Nearby hammerstones for smashing bone may have been used earlier for knapping.

Figure 12. Middle phase marrow extraction stations

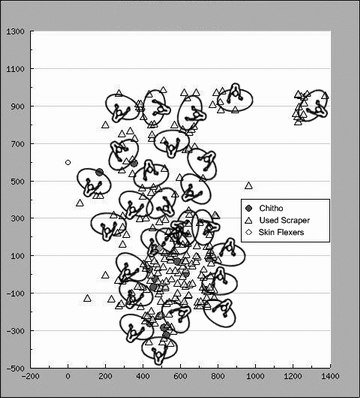

For the sixth activity (Figure 13) or hide preparation, we plotted used scrapers and chithos, the latter being thin rough sandstone discs pulled scraperlike at a steep angle out from the centre of a pegged hide to stretch and soften it. Assuming these tools were not completely dispersed over the years this floor was used, their distribution would form a partial arc of a hypothetical 60-90cm oval hide. To reduce subjectivity, we designed algorithmic crawler software to penetrate the palimpsest to look for 60-120º arcs of scrapers and chithos along hide borders, also finding 26 stations (Figure 14).

Our seventh and final activity is woodworking (Figure15). Tool handles were split from spruce poles with a wedge, sawn to length with a denticulate, shaped with a pushplane and rounded with a spokeshave. We inserted five icons of men, but more are obviously needed.

Figure 13. Middle phase hide preparation stations by query |

Figure 14. Middle phase hide preparation stations by algorithm |

Figure 15. Middle phase woodworking stations |

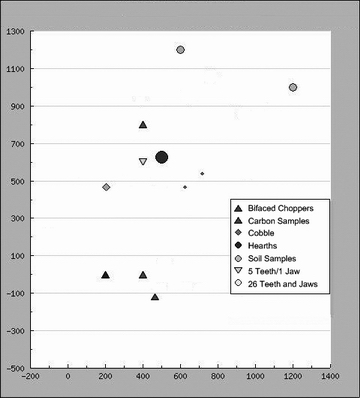

Figure 16. Middle phase palimpsest leftovers |

Removing artifacts of all seven activities from our palimpsest resulted in an empty hearth (warmth, insect repelling or hide tanning), a tent weight cobble, uncalcined jaws and teeth not in hearths, charcoal and soil samples and a chopper (Figure 16), all present in Figure 3 but absent in its legend due to space. It may be possible to use dated artifacts of identical hue in nearby sites to chronologically arrange the knapping sequence of KjNb-7 over its 400 year occupation.

* * *

In sum, palimpsest spatial analysis reflects the conservative nature of hunters and their families to use the same areas of a campsite for the same sequence of activities and allow delineation of gender-based activity areas. Our techniques are beneficial if you have repeated site usage in any time period.

Acknowledgments

I thank my XY Spatial Analysis Group for its input. Results were possible due largely to software programmers Raymond Cheng (main customized program) and Ricardo Santiago (algorithmic crawler method). Final publication figures were done by Elizabeth Creary (also text editing) and Alanna Caples (figure arrangement and graphic art), with overhead human icons by Sylvie Pelletier. For testing palimpsest deciphering, many figures were first generated by Katherine Herbert and Lori Howey. I thank them all for lively discussions on icon orientation and symbol selection. There was general agreement once activity parameters were established.

Dr. Bryan C. Gordon, Research Division

Canadian Museum of History

100 Laurier St, P.O.Box 3100, Station B

Gatineau,Quebec, Canada J8X 4H2

Comments: bryan.gordon@museedelhistoire.ca