Introduction

Pictographs and petroglyphs are worldwide and may result from vision quests and religious or shamanic experiences. While some simply mark territory, events, astronomy and hunting scenes, others result from hallucinations induced by drugs, starvation, thirst or sex, their meaning unprovable. Some relate to serotonin-induced migraines caused by restricting blood flow to the brain. Old World wall art dates from the Historic period to 70,000 years at Blombos Cave in South Africa (Henshilwood et al. 2002), 40,000 years in Australia, 35,000 years in Fumane Cave near Verona, Italy, 32,000 years in Chauvet Cave in southern France and 5500 years in India. The most famous wall art is Magdalenian, dating 20,000 years in Lascaux and Montespan Caves in southwest France, and 17,000 years in Altamira in northern Spain. Other Old World art has similar age, while New World art verges on 8000 years.

We are constantly amazed how beautiful ancient art can be, so it is fascinating to know when an artist worked. Art also dates its culture and allows its tracking across the land, so it is crucial to Native land claims. Eight methods for dating rock art existed 40 years ago: stratigraphy, superposition, style, weathering, lichenometry, ethnohistory, prehistory and lab methods. None were worthwhile for the following reasons. Underlying soil with similar datable mobiliary art is rare, while superposed paintings only determine their sequence, not their date. Style dating problematically relies on time progression, the first radiocarbon dates of Lascaux’s stylistically-dated paintings being wrongly rejected. Lichen growth could begin any time after the art, while ethnohistoric records of the art seldom exceed a century. Carbon dating of organic paint binders, also problematic, includes accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), spectroscopy, amino-acid analysis, chromatography and scattered electron microscopy (SEM). AMS is the most promising but binders may include dead carbon brought up as sap from the soil (e.g, oxalic acid in cactus sap used as binder).

A New Method Of Dating Wall Art

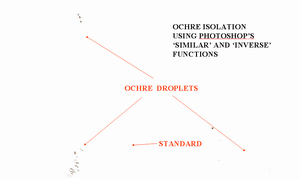

Although fallen petroglyph fragments are detected in the underlying soil using our method, we emphasize pictographs here. Pictographs include ochre and other pigments applied as chalk or paint, their dust or droplets falling invisibly to the floor to be covered with new soil. The problem is their separation from ferromagnesian compounds with a similar RGB (red, green, blue) colour values range. Our technique handles faded or visible art, common colours being red or yellow ochre, black manganite or white or cream caliche. A digital camera and laptop with filtering software, plus quite dry sediment under the art are needed. Photoshop works fine with its Similar and Inverse functions, while web downloadable Paint.Net and GIMP have equivalent commands. Dating the particles or paint droplets requires only a mg of charcoal, wood or bone in each 5-7mm scraped level or peel. These are normally present because hearths were used for heating paints and for lighting. We hope to add a live feed from camera to laptop filter to screen so we can observe particles onsite for extraction and later SEM analysis to confirm pigment composition.

Indoor Testing

From summer through winter of 2007-8 we prepared many indoor pictograph mockups on an 80 x 80cm plywood sheet hinged at the back of a standard artifact drawer. On a tripod we vertically mounted a high resolution digital single lens reflex camera with zoom lens and flash. After adding 10mm of white blasting sand across the drawer, we applied red and yellow ochre or various colours of school chalk in separate areas on the plywood as it overhung the drawer. After miniscule amounts of chalk dust fell on the sand, the plywood was swung out of the way to photograph the sand surface. Another 10mm of sand was sifted evenly overtop, the dusting repeated from another pictograph pattern and colour, and photographed. This process was repeated until the sand was 30-40mm deep. Then 5-7mm levels or ‘peels’ of sand were scraped away with a rectangular masonry trowel held vertically. These scrapings were discarded indoors but would be used in the field work because there they may have charcoal, plant, shell or bone fragments for dating, plus any artifacts. As we already knew the RGB values of our pigments, we easily confirmed them on white sand with photofiltering. To assess interfering ferromagnesian compounds we tried beige cement-quality and dirty grainy playground types of sand. We encountered birefringent or edge-effect colours resembling ochre on large sand grains or small gravel, but these can be avoided so we focussed on the few brighter pixels inside the ochre-like clumps.

Field Tests

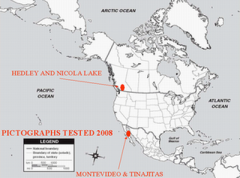

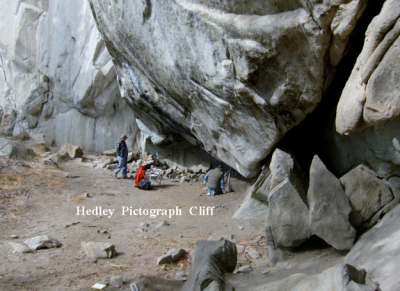

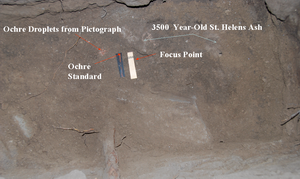

Field tests were done in the Hedley rockshelter in British Columbia and the Montevideo and Las  Tinajitas rockshelters in Mexico. All have soil under their walls or ceilings for pigment determination. The Nicola boulder pictographs remain untested. In March, I was invited by archaeologist Brenda Gould of British Columbia’s Upper Similkameen First Nations Band to date the art in the Hedley rockshelter. Above its dry dark or ashy soil are many orange-brown pictographs, some so bright they appear modern. I chose three test areas (A to C) based on soil thickness vertically below highly visible art.

Tinajitas rockshelters in Mexico. All have soil under their walls or ceilings for pigment determination. The Nicola boulder pictographs remain untested. In March, I was invited by archaeologist Brenda Gould of British Columbia’s Upper Similkameen First Nations Band to date the art in the Hedley rockshelter. Above its dry dark or ashy soil are many orange-brown pictographs, some so bright they appear modern. I chose three test areas (A to C) based on soil thickness vertically below highly visible art.

Facing the cliff, test area A was placed deep under an overhang and B was placed below a faded pictograph on a fallen boulder because the painting was less than a meter above the sloping boulder face where the pigment particles were most apt to slide. I placed C in mid-shelter under a repeatedly painted vertical band whose particles or droplets were more apt to fall.

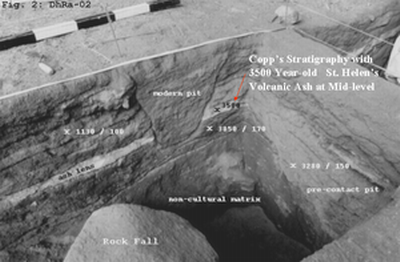

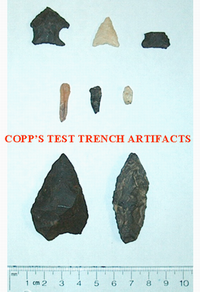

Test A produced 34 peels to below the ash, but had little datable material. Ochre photofiltering remains unfinished. Test B below the fallen boulder had 40 peels to the volcanic ash at 40 cm subsurface. As predicted, red ochre particles were found along the fall line of the boulder. Test C had the best results, producing 30 peels to a depth of ca. 40 cm, where visible red ochre was found on the volcanic ash overlying cave rockfall. Removal of non-ochre colours by Photoshop filtering revealed only ochre particles and droplets. Plant, beetle and bone fragments were collected in most peels for identification and AMS dating.

In April I led an expedition to Baja California Norte to the sites of Montevideo and Las Tinajitas.  Photographing and interpreting the art had been the focus in Baja wall art research, with little excavation to reveal the life of the artists. Notable exceptions include Californians Clement Meighan and Eric Ritter. In 1962, Meighan carbon-dated a wooden peg from a crevice in the rock art site of Cueva Pintada at 530±80 years, adding 139 artifacts with paint brushes notably absent. Consistent style of humans, deer, mountain sheep, rabbits, birds and fish suggested a short artistic period, a few generations to two centuries. As drought and overhunting may have depleted game, Meighan suggested hunting magic was used in the paintings to restore the game but failed, and the caves were abandoned two centuries before the Spanish, with the people moving to the coast. In our area Ritter found they had had both mountain and coastal adaptations. Since their work, 700-2100 year-old estimates in the UN Heritage wall art in the Sierra de San Francisco support Meighan’s date, but dates here and in the Sierra de Guadalupe by Australian Alan Watchman extend the age. Several of his >30 samples collected in 2001 dated at least 5000 years, with some 7500 years, suggesting an artistic tradition lasting millennia.

Photographing and interpreting the art had been the focus in Baja wall art research, with little excavation to reveal the life of the artists. Notable exceptions include Californians Clement Meighan and Eric Ritter. In 1962, Meighan carbon-dated a wooden peg from a crevice in the rock art site of Cueva Pintada at 530±80 years, adding 139 artifacts with paint brushes notably absent. Consistent style of humans, deer, mountain sheep, rabbits, birds and fish suggested a short artistic period, a few generations to two centuries. As drought and overhunting may have depleted game, Meighan suggested hunting magic was used in the paintings to restore the game but failed, and the caves were abandoned two centuries before the Spanish, with the people moving to the coast. In our area Ritter found they had had both mountain and coastal adaptations. Since their work, 700-2100 year-old estimates in the UN Heritage wall art in the Sierra de San Francisco support Meighan’s date, but dates here and in the Sierra de Guadalupe by Australian Alan Watchman extend the age. Several of his >30 samples collected in 2001 dated at least 5000 years, with some 7500 years, suggesting an artistic tradition lasting millennia.

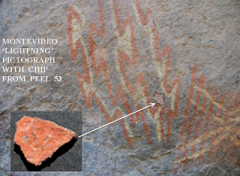

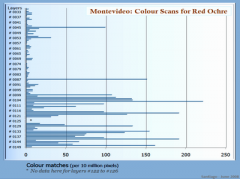

At Montevideo we tested the soil under the ‘lightning bolt’ pictograph on the main wall at the vehicle turn-around. Our 20 x 50 cm test slit was enlarged slightly to the west when we encountered the sloping cliff wall. We scraped 146 peels with fragments of charcoal, plants, shell, bone or stone flakes in most levels. Of great interest was a pigmented rock chip from the pictograph in peel 53 found above mid-depth. Peel 53 has a potential minimum AMS date for the painting and indicates that fallen ochre should be even lower when the art was made. To find this red ochre we ran 20 second automated photoscans of peels 33-149 using a narrow RGB window. Selecting the most prolific scans and using Paint.Net, we enlarged and examined their photos using a pre-selected saturation. Visible red ochre chips in peel 79 suggest their use in the lightning bolt. To find the locations of less visible pigment particles we used the Similar and Inverse functions in Photoshop.

At Montevideo we tested the soil under the ‘lightning bolt’ pictograph on the main wall at the vehicle turn-around. Our 20 x 50 cm test slit was enlarged slightly to the west when we encountered the sloping cliff wall. We scraped 146 peels with fragments of charcoal, plants, shell, bone or stone flakes in most levels. Of great interest was a pigmented rock chip from the pictograph in peel 53 found above mid-depth. Peel 53 has a potential minimum AMS date for the painting and indicates that fallen ochre should be even lower when the art was made. To find this red ochre we ran 20 second automated photoscans of peels 33-149 using a narrow RGB window. Selecting the most prolific scans and using Paint.Net, we enlarged and examined their photos using a pre-selected saturation. Visible red ochre chips in peel 79 suggest their use in the lightning bolt. To find the locations of less visible pigment particles we used the Similar and Inverse functions in Photoshop.

Analysis and Interpretation

Our international field trials introduced variables absent in indoor testing – faded paint and diverse sediments. We also found that paint can penetrate 8mm of rock, retaining its original RGB values in faded pictographs by centering Photoshop’s Eyedropper in tiny preserved areas. Outside their center where the paint is pale or thin, the colour of the underlying rock substrate will show through and alter the RGB values. As the sediments under the art varied from dry white sand to black or ashy soil, interfering ferromagnesian RGB values must be excluded in our analysis. Fortunately, their range differs somewhat from ochre RGB values.

Conclusion

We used a non-destructive field technique using high resolution photofiltering of 5-7mm thick soil peels for detecting pictograph pigments or petroglyph chips below rock art. Most peels contain charcoal, bone and plant specks for AMS dating, which is ongoing.

References

Copp, Stanley Arthur 2006. Similkameen Archaeology (1993-2004). Unpub. Ph.D. thesis. Dept. of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia.

Dewdney, Selwyn 1970. Dating Rock Art in the Canadian Shield Region. Occasional Paper 24, Art and Archaeology, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Henshilwood, C. S. Francesco d’Errico, Royden Yates, Zenobia Jacobs, Chantal Tribolo, Geoff A. T. Duller, Norbert Mercier, Judith C. Sealy, Helene Valladas, Ian Watts, Ann G. Wintle 2002. Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa. Science 295:1278-1280; Feb. 15.

Meighan, C. 1966. Prehistoric Rock Paintings in Baja California. American Antiquity 31:3:372-392.