Dating Pictographs and Petroglyphs: A new non-destructive method using high-resolution pigment and pocked particle photography

Canadian Archaeological Association, Calgary, April 28 – May 2, 2010

By Bryan C. Gordon, Canadian Museum of Civilization

Eight unreliable rock art dating methods existed 40 years ago – stratigraphy, superposition, style, weathering, lichenometry, ethnohistory, prehistory and lab methods. Some have been improved. A level with similar datable portable art like figurines under the wall art is rare, as is subsurface rock art in contact with datable levels. Superposed paintings only determine their sequence, not their date. Style and age may show no relationship. The first radiocarbon dates of Lascaux’s stylistically-dated paintings were rejected in the 1950s. Historic dating conflicts with the supposed Palaeolithic Coa Valley petroglyphs in Spain. For lichenometry, lichen growth can begin any time after the art. Pre-literate ethnohistory is useful only if an artistic oral tradition exceeds several centuries. Even then its meaning may be untested. Methods for dating organic pigment binders include carbon dating, accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), spectroscopy, amino-acid analysis, scattered electron microscopy (SEM) and chromatography. All are problematic because binders may include dead carbon brought up as sap from the soil, like oxalic acid in cactus, which increases age. Our method is non-destructive, non-invasive and simple, and may not need a full excavation permit. As I rarely find stone flakes in the small scraped soil slot vertically below the art and never human bone, NAGPRA and museum repository needs have been exempted. In the unlikely event that they occur, the slot can be infilled and another slot tested alongside. Tests involve photography and screening of 5mm levels in a 20×30 cm soil slot below the art. Fallen pigment dust or droplets and petroglyph or hammerstone fragments can be dated in sequential levels with tiny charcoal, plant, shell and bone fragments in the same levels. This is vital because art often involves many visits for ceremonial and other reasons, an important trait within landscape archaeology.

Rock art is the most mysterious, personal and irreplaceable part of human ancestral remains. It shows the basis for human symboling, language and cognition. Rock art originated several hundred thousand years ago in the Lower Palaeolithic. Its earliest known pictographs and petroglyphs are in central India, Sudan and the Korannaberg of South Africa, while the earliest in Europe is at La Ferrassie in southwest France. There are thousands of Pleistocene rock art sites in Australia, while the oldest American art is in Argentina. Wall art marks territory, hunting and astronomical events or drug, starvation or thirst-induced vision quests or shamanic trances. It occurs wherever there was a will to paint, peck, draw or adjust rocks on a rock surface. Whether symbolic, narrative or mythical, ignorance of its dating diminishes insight into its meaning. A reliable date will enhance its interpretation. This is especially important in landscape archaeology because we can compare contemporaneous motifs in different locations. With dating, archaeologists can better treat motifs within their landscape, rather than separately.

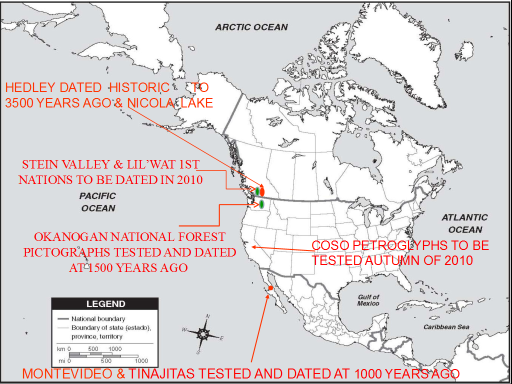

For rock art leads we ask others or probe the internet, selecting photos with underlying soil which might have pictograph, petroglyph and hammerstone particles. In field tests we link these to their art by applying wet glue-covered paper to each level, removing particles later for SEM analysis. We sift levels for AMS-datable debris. Particles seen in laptop-enlarged photos should correspond to their glue sheet locations. If locations conform, we think 1-2 are due to weathering; more reflect art application. (Slide 2) Our method improved with each test, involving 20 pictographs in 5 regions of 3 countries. We tested the Hedley, Montevideo and Tinajitas rock shelters, plus the Nicola boulder sites in British Columbia and Mexico in 2008. Then we returned for the Stein Valley cliff in British Columbia and three American Okanogan boulder sites in 2009. I begin with the Mexican sites so that I can later focus on Western Interior Plateau rock art where most updates on testing, the use of glue papers and colour enhancement were made (Slide 3). We also reconstruct weathered and vandalized pictographs using pigment particles that penetrated the rock and remain invisible to the naked eye.

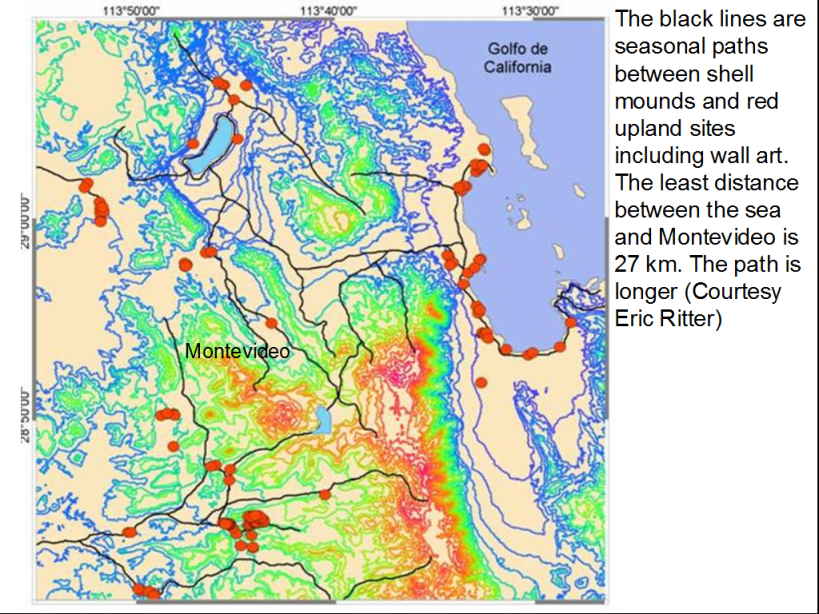

In addition to rock patterns on the ground (petroforms), landscape archaeology includes pictographs and petroglyphs on cliffs, boulders and cave walls. Some have been portrayed as supernatural places where spirits of the air, water and rock co-mingle, where shamans enter and leave these realms on behalf of their people. (Slide 4) Some are seasonally visited and are important in landscape archaeology. Montevideo and other upland sites in Baja California were on seasonal rounds of people who lived as fishermen on the coast of the Gulf of Cortez.

The black lines are paths between their coastal shell mounds and ceremonial rock art. The shortest distance between the sea and Montevideo is 27 km but the path is longer. (Slide 5) Montevideo consists of several hundred meters of cliff wall with dozens of motifs. We selected the most prominent motif, which we called the Lightning Bolt, having deep undisturbed sand below 5-10cm of trampled sand and surface litter. The inset shows a motif chip found about 25cm subsurface. (Slide 6) To reach it we scraped away with a vertically-held mason’s trowel and used a tripod-mounted DSLR to photograph each level. (Slide 7) As the chip came from level 53 for a minimum date, we scraped past one meter, finding visible red ochre in level 79 at 40 cm, with some particles even deeper but without datable material. Charcoal with red ochre dated 830-980 ± 40 BP (measured & conventional; Beta 268557). Red ochre particles in several levels suggest multiple visits to the site. (Slide 8) About 20 km southwest we placed 3 test slots in two Tinajitas caves but did not date them due to costs. But we enhanced ceiling art to show sun, human and animal motifs for later comparison (Slide 9).