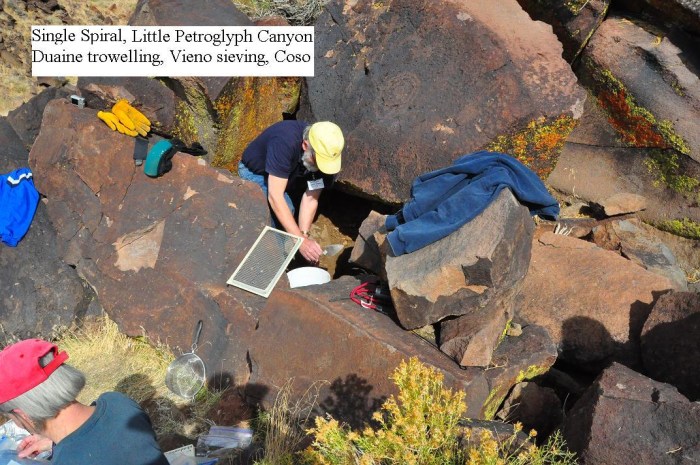

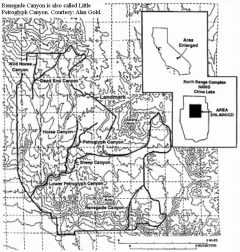

On October 27th to 29th, 2010, a field party under my direction tested thin soil levels for art debris under the Double and Single Spiral and Bear Paw petroglyphs in Little Petroglyph Canyon. The canyon is located in the Coso National Monument in the north range of the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Range of south-central California (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: 2010 Study Areas

The petroglyphs are all near the canyon mouth, the Bear Paw panel higher and on the opposite slope of the canyon several hundred meters down the canyon. I chose the Double and Single Spiral motifs on the advice of Sandy Rogers, a local archaeologist and tour guide. He believed these simple motifs may be older than the well-studied and common Coso sheep motifs. I chose the Bear Paw panel because it portrayed spear throwers dating back about a millennium. Our three motifs are well above the canyon floor, avoiding any soil disturbance from flash floods and tour groups that may affect their testing. We do not attempt to interpret the meaning or orientation of the three motifs.

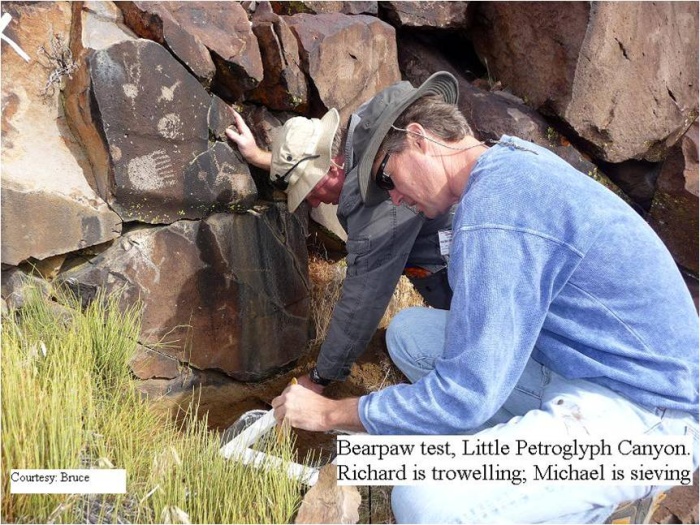

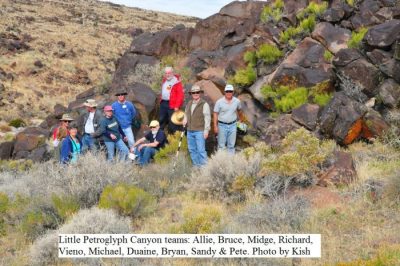

Little Petroglyph Canyon boulders are whitish rhyolite covered with dark desert varnish, giving them the external appearance of black basalt. Motifs were made by pocking through the varnish to reveal the lighter rhyolite. There was little evidence of grinding. The Navy shortened my allotted time from four days to six hours, making it impossible to check sterile sand away from the rock art as a blind test. This had been recommended at the International Federation of Rock Art Conference held earlier in France. I was still able to test soils under three petroglyphs down to rock or sterile sediment with three 3-person crews (Fig. 2).

Laboratory Tests Prior to Fieldwork

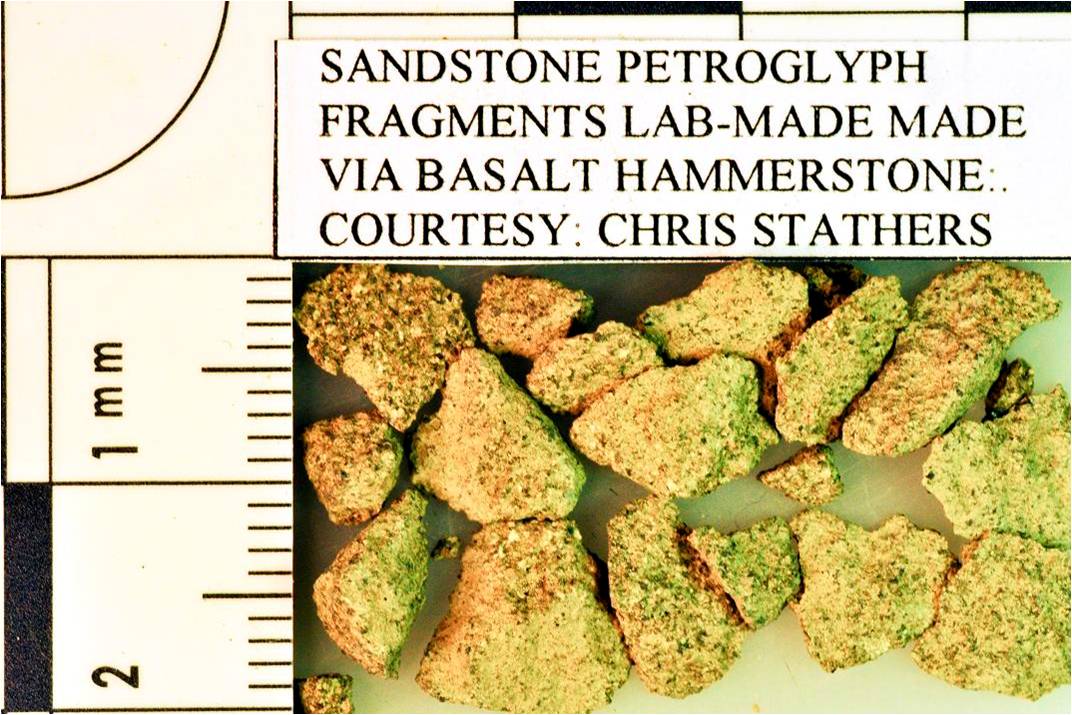

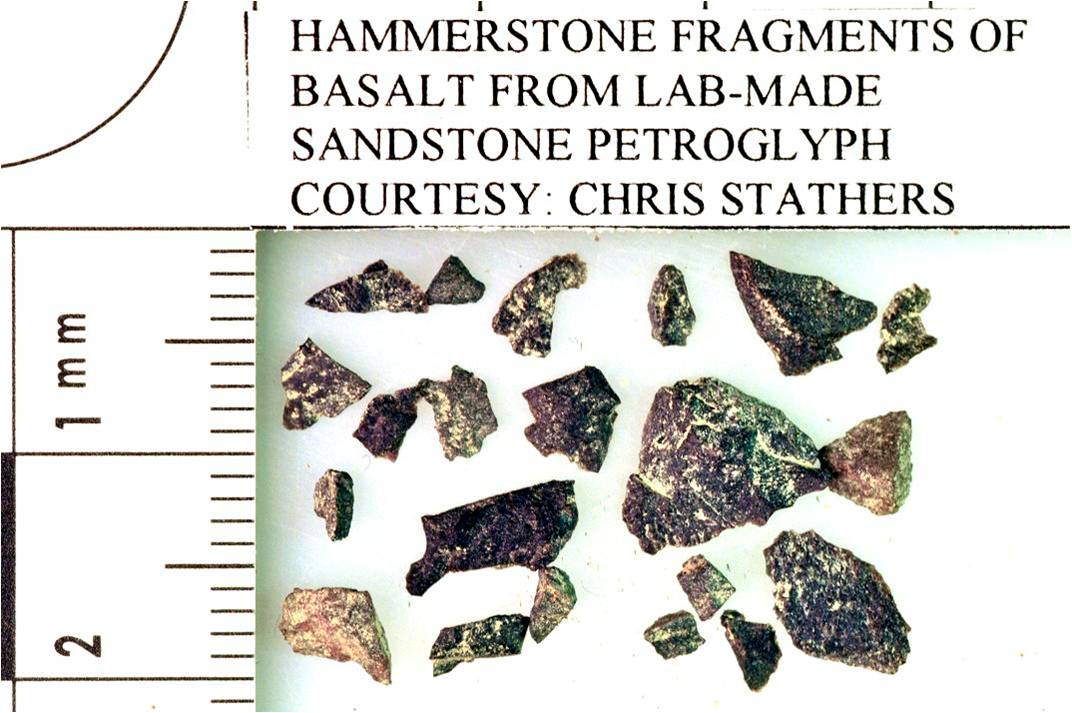

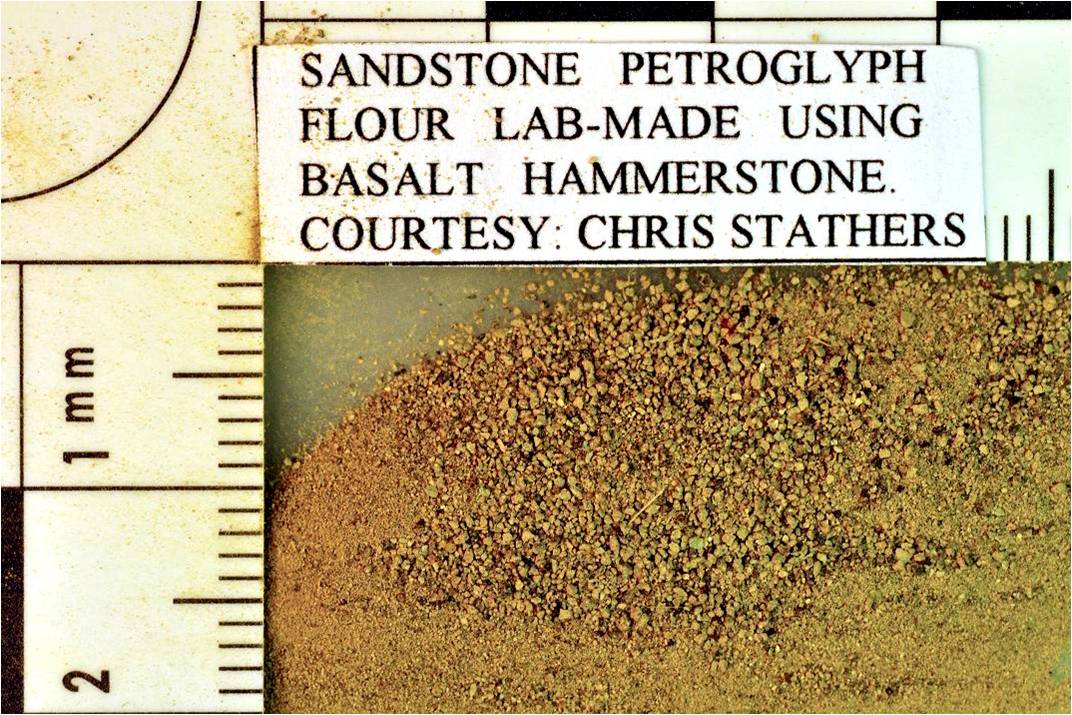

Before our visit we analyzed debris from artificially-made sandstone slab petroglyphs resting on a clean concrete floor, courtesy of Christine Stathers. We found that a common kitchen deep fry basket (4 mm mesh) captured her few large basalt hammerstone chips (Fig. 3) and sandstone parent rock fragments (Fig. 4). A common kitchen sieve (1 mm) retained smaller chips and fragments (Fig. 5). The remaining sandstone ‘flour’ smashed by her hammerstone passed through into a tray (Fig. 6).

Microscopy shows this ‘flour’ to be white from size reduction, even when it came from dark sandstone. Hammerstone blows suggested particles of this flour may be flatter than normal weathered and rounded soil particles. Their ratios of degrees of sphericity into the 250 micron range in archaeological sediments shows slowly decreasing flatter and increasing rounder soil particles with magnification. Since this trend was not conclusive we did not attempt scattered electron microscopy, but their visual ratio appears to confirm the flour came from hammerstone blows.

Before testing we decided to remove 12 mm level thicknesses because art tools or their chips exceed 5 mm thicknesses used in finding pictograph pigment particles. Using small rectangular trowels we also reduced our test area to 10 x 20 cm, rather than our usual 20 x 30 cm, because we wanted less impact working in a national monument. We later backfilled our tests with debris that had passed through our filters. Using pre-test photographs as guides we replaced natural vegetative debris on the ground surfaces in their original form, and then brushed away any footprints.

Testing the Double and Single Spiral and Bear Paw Petroglyphs

I chose the concave-faced Double Spiral petroglyph boulder (Fig. 7) because hammerstone and parent rock art chips and rock flour might have been funnelled onto its soil where we placed our test (Fig. 8). The Single Spiral motif (Fig. 9) was enclosed by high boulders, trapping flying hammerstone and art chips and being less susceptible to soil disturbance. Crew members Duaine and Vieno did, however, encounter an abandoned nest and humerus of a desert rat.

The Bear Paw petroglyph (Fig. 10) was almost at the canyon rim and was half surrounded by boulders that may have deflected flying debris to our test soil. As motifs contrast greatly with sun angle, the Single Spiral motif was enhanced using computer software (Fig. 11). It revealed older motifs invisible to the naked eye that likely correspond to art debris found in lower levels (Table 1).

Hammerstone rock type is likely quartz, based on its being found in petroglyph carving in the Mojave Desert. I found an unaltered quartz cobble on the canyon floor and used it to penetrate desert varnish on an unaltered rhyolite cobble to make the white rock flour. Soil below the Single Spiral motif yielded 21 arbitrary 5 mm levels to a depth of about 10.5 cm (Table 1). Sharp quartz chips possibly from hammerstones were only in levels 6 and 7, and quartz fragments in levels 12 and 19 may have originated likewise. Naturally fallen rhyolite chunks were in most levels, as were carbon samples. Eight levels had common pebbles, and rhyolite flour was absent because line grinders were not used.

Soil below the Double Spiral motif was tested down twelve 5 mm levels to 6 cm. Possible sharp quartz hammerstone chips were in levels 1, 3, 4, 7 and 9 to 12, when testing was terminated (Table 1). Weathered quartz and quartzite pebbles were in levels 4, 5 and 6, while levels 8 and 9 contained rhyolite rocks and pebbles which had likely fallen naturally from their boulder. Carbon samples were in all levels, as was rock flour.

The Bear Paw motif had ten arbitrary 5 mm levels to a depth of 5 cm (Table 1). Possible quartz hammerstone chips were in all levels except 6 and 8. Rock flour was in all levels except 1, 6, 8 and 10. Unlike the other two panels, quartz crystals from hammerstones were absent. Carbon samples were in all levels except 7, with much organic material in levels 2, 3, 5 and 9. Quartz fragments and particles were again absent but fragments of other stone were in most levels.

In conclusion, all three petroglyph panels tested at Coso were likely made in stages, although their individual shallow motifs barely penetrated the desert varnish and were likely done in one stage. Line grinders may have been used, but hammerstones were the tool of choice. The hidden motifs enhanced on the same panel as the Single Spiral motif were likely done at an earlier date. The complex Bear Paw motif may have been done in one stage with its associated millennial-old atlatl motifs because they are slightly but very evenly weathered. Dating panel growth stages may lead to accepting that much rock art was done or reapplied over periods of time. It may also help us to fully comprehend the true length of artistic traditions. Samples for radiocarbon and AMS dating are all categorized at the Museum and await funding by interested individuals.

Acknowledgements

Duaine and Vieno Lindstrom, Michael and Richard Heath, Pete McQueen and Bruce Thompson tested the Single Spiral and Bear Paw tests. Kish LaPierre and Sandy Rogers were helpful in guiding us to Little Petroglyph Canyon and assisting in testing the Double Spiral motif with Midge Gordon. At the Museum, Don Gribble, Alicia Ghadban and Frank Bayerl separated samples using sieving, flotation and microscopy. Frank proofread this paper.