Rekindling the Fire: Carleton Research Project hosts gathering for First Nations pursuing self-government

By Ben Sylvestre

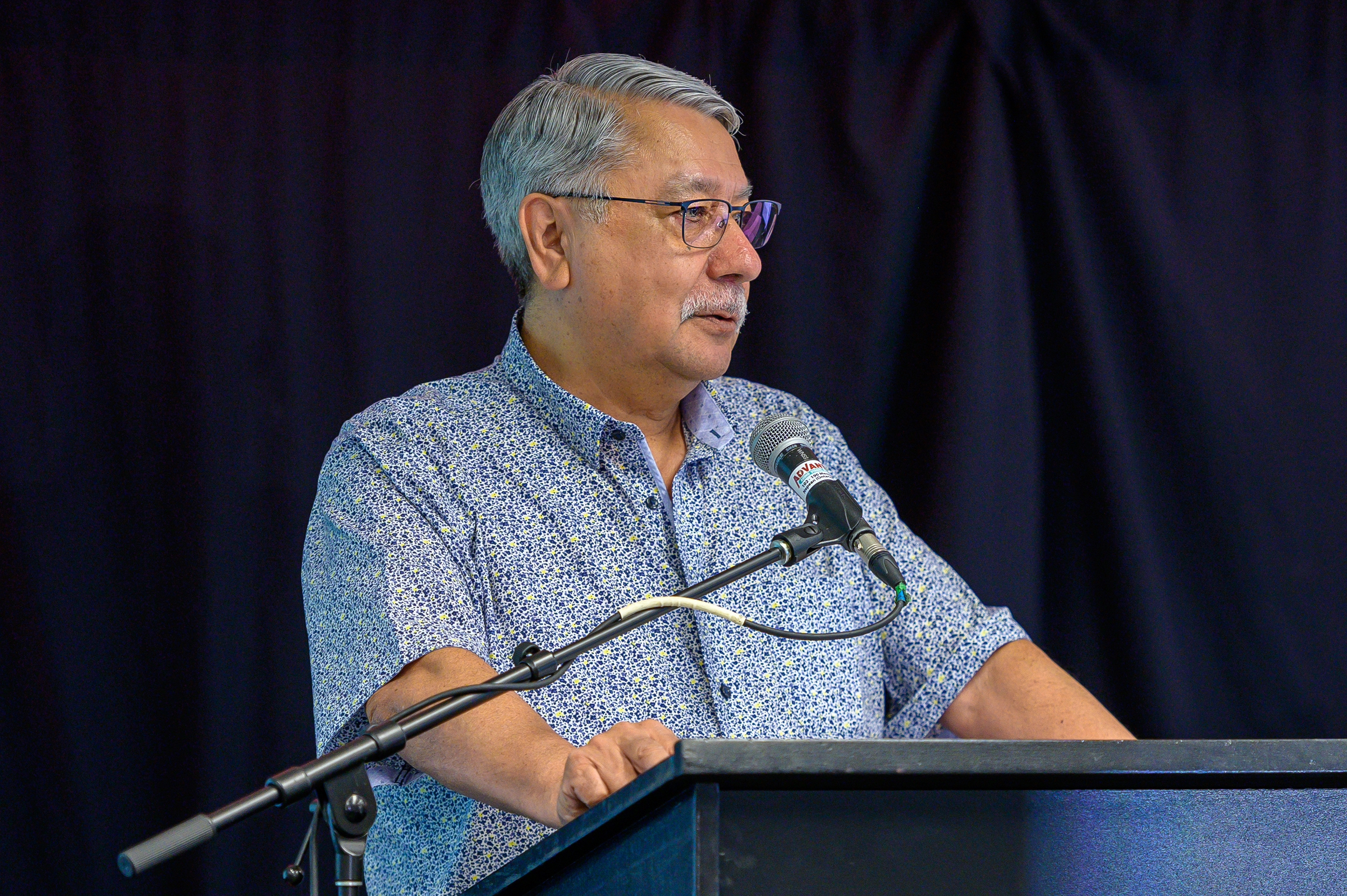

“Right now, as we talk, the babies that are being born today are the eighth generation under the Indian Act, and we need to free ourselves from that.” – Satsan (Herb George)

The president of the Centre for First Nations Governance (CFNG) and project co-director of the $2.5 million SSHRC-funded Rebuilding First Nations Governance Project (RFNG) at Carleton University addressed First Nations leaders, community members, and allies gathered in a Teraanga Commons conference hall.

Rekindling the Fire, a gathering co-coordinated by both organizations, offered First Nations across Canada a space to discuss how to re-establish their traditional forms of government and leave behind the Indian Act.

The two-day event included ceremony, panels, speakers and workshops to help First Nations partnered with RFNG and CFNG take back control over their communities from Canadian colonialism.

“This project is designed to help you implement your right according to your vision and your priorities, your creation story, your oral history, from your people,” said Satsan.

Re-igniting the self-governance spark

For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, First Nations across Turtle Island (North America) organized themselves into unique nations, each stewarding their own lands and communities through their own systems of government. Canadian colonization destabilized First Nations’ control over their own affairs, but the inherent rights they have always had as nations separate from Canada never faded away.

Although Canada imposed the Indian Act system of colonial governance, First Nations still have the inherent right to govern themselves without it—just as they have for millennia. Nations from coast-to-coast are now starting their journey back to self-government, leaving behind the Indian Act and its continued oppression.

“We’ve been interrupted for over 150 years under the Indian Act, from exercising our own responsibility for ourselves,” said Satsan. “We’ve lost that skill set along the way. We haven’t got the experience to do it. So we’ve got to pick it up, and we’ve got to learn how to do it again.”

That’s where CFNG comes to help. The non-profit supports nations to rebuild their self-governance ability through in-depth training with experts on Indigenous governance, law, language, history and more.

“We get them to this place where they can start to talk about their vision for the future of our children, our grandchildren and those yet unborn,” said Satsan.

Once a First Nation decides it’s time to begin its journey back to self-government, Carleton’s RFNG research project supports the nation’s research and information needs as its citizens investigate their past self-government, present-day priorities and future goals.

Both CFNG and RFNG also connect nations to one another for cooperative learning opportunities through in-person gatherings like Rekindling the Fire and free online events.

“When we consolidate the collective experience of all of the different nations who are working on nation rebuilding through creating an action network…, they can learn from a collective experience, and they can help each other to rebuild their nations,” said Satsan.

Together at last

Rekindling the Fire brought nations partnered with RFNG and CFNG from across Turtle Island into a single space for the first time since RFNG was launched at Carleton three years ago.

Elder Saw̓t (Martina Pierre) of Líl̓wat Nation, joined other Elders speaking in a panel about their visions for the future of their communities. Saw̓t, a teacher who helped establish the central B.C. nation’s community school 50 years ago, says First Nations people need to clear their own paths to overcome the legacy of residential schools, climate change, and colonization.

“Today I’m 86 going on 87. But my commitment to our people—the Indigenous peoples—is to look at those challenges and create something to empower us to stand up, take our land back,” she said.

Líl̓wat is partnered with both CFNG and RFNG to access training and knowledge on how the community can take positive steps towards rebuilding its traditional governance system as a unified nation. Saw̓t and other Líl̓wat citizens are running events and managing new community projects to educate all people of Líl̓wat on how they can collectively chart their nation’s future.

“Every chance I get, I talk to people about our inherent rights movement in our own community,” she said.

Cindy Tom-Lindley joined a delegation from Upper Nicola as both a speaker and participant in Rekindling the Fire. Much like Líl̓wat, the syilx Okanagan nation from British Columbia’s interior brought along elected officials, youth, Elders, and community members to learn and share knowledge.

“One of our tasks for a gathering like this one is to spark those ideas with each other, to lift each other up,” said Tom-Lindley. “All of us have been working very hard and some of us for a very long time to make some changes for our children and our grandchildren.”

“Part of this process that’s really important is that we look to each other, we hold each other up and we give each other the energy, the support and the ideas that we need to carry on and keep fighting.”

The knowledge to self-govern

But Rekindling the Fire isn’t just a platform for mutual support. The event offered First Nations practical guidance on self-government from experts with direct experience and careful study.

Naomi Metallic of Listuguj Mi’gmaq Nation, Chancellor’s Chair in Aboriginal Law and Policy at Dalhousie University and RFNG’s Peace & Friendship Treaties Co-Leader, presented a brief overview of Indigenous Lawmaking. The lawyer and educator highlighted how First Nations can revitalize their laws and legal traditions from before colonization by drawing on their language, even if there are few fluent speakers.

“Maybe it’s because we’ve allowed law and politics to seem like such a practice of the elite that we don’t see it as actually part of how we interact with each other, and maybe we should. That’s how our ancestors did it, right?” she said.

“We also think about it as just rules. It’s just like a law in a book,” she added. “It says thou shall not do X or Y. But law is so much more than that.”

Indigenous laws instruct people on how to solve problems, make decisions, manage resources and more. Rather than being written down like in the Canadian legal tradition, Indigenous laws are often baked into the messages behind oral histories, cultural practices, and languages.

“We can then take these things and use them today to govern our communities in ways that we see fit,” she said.

The next generation of leaders

Pictured here from left to right are (front row) Satsan (Herb George), alongside IRYI Youth Ashley Bach, Daphne McRae, (back row) Darian Agecoutay, Lexlixatkwa7 Nelson, Serena Smith and IRYI Coordinator Amsey Maracle.

Rekindling the Fire also showcased youth involvement in First Nations self-government. At the gathering’s celebratory feast at Mādahòkì Farm, young people from the CFNG and RFNG’s Inherent Rights Youth Initiative (IRYI) took the stage to unpack their learnings from the online initiative’s educational gatherings.

Darian Agecoutay, from Cowessess First Nation, says IRYI inspired him to recognize his rights as an Indigenous person don’t just come from the treaties his peoples signed with Canada: they originate from his citizenship to a unique nation pre-dating Canada by thousands of years.

“Having these sessions really assisted me in getting out of that type of thinking, because I’m not just a Treaty Indian anymore. That’s what it says on my status card. I know I’m Indigenous to the land now. And I have the rights that are accompanied with it,” he said.

Emerging leaders, like Agecoutay, played an active role in Rekindling the Fire, sharing the governance expertise they gained from IRYI sessions and their personal learning journeys.

IRYI member representing Líl̓wat Nation, Lexlixatkwa7 Nelson, says this event has been a valuable chance to connect.

“I was excited about getting to meet everyone in person that I’ve been talking to online for two years now. It was really cool being able to discuss in a much more natural, face-to face way. Everyone, even just today, has been saying stuff that I’ve been thinking about for so many years now,” Nelson said. “It’s (about) finding people that have the same ideologies or the same hopes for our future.”

The next steps of the self-government story

Both RFNG and CFNG plan to continue fostering connections for First Nations peoples across Turtle Island. The organizations’ efforts are more than standard outreach: both aim to build a future where First Nations can better support one another in self-government.

“One of the wonderful, exciting things about this project is being able to bring together and reach out to experts and people who have lived this from right across Canada and indeed into the United States,” said RFNG project manager and School of Public Policy and Administration (SPPA) fellow, Catherine MacQuarrie.

“I get to be inspired by all these people several times a week,” she added.

RFNG Project co-director Frances Abele, Carleton’s Distinguished Research Professor and SPPA Chancellor’s Professor Emerita agrees that the collective effort is motivating.

“We have a large number of wonderful, serious, positive people working on the most important things. It’s magic,” she said.

By the end of RFNG’s SSHRC grant period in 2027, the research project will have created a “roadmap” and other tools First Nations can use to reconnect with their traditional self-government systems, usher these systems forward into the contemporary age, and allow nations to begin their exit from the Indian Act.

“What we’ll end up with is an inherent rights transitional governance model that all other First Nations can use across this country,” said Satsan.

“We can rebuild our nations. And we can look to the seven generations that we talk about rhetorically and realize that we are the first generation to be free.”

Continue your learning journey

First Nations interested in learning more about inherent rights and Indigenous self-government can contact the Centre for First Nations Governance (CFNG) or access the free materials on the Rebuilding First Nations Governance (RFNG) website.