You asked – our experts answered. Follow us @cubutterflies on Instagram for more butterfly facts!

- Do butterflies make sounds?

-

Many butterflies have ears that they probably use to detect the sounds of approaching predators, but very few butterflies actually make sounds. One good example of a sound producing butterfly is the Hamadryas butterfly, sometimes called the ‘cracker’. It has little sound producing organs on its front wings that make cracklings sounds. They make these sounds when approached by a predator, perhaps using it as a warning sound. Sometimes they also use these sound during mating interactions, in which case they would be communicating. – Dr. Jayne Yack

Additionally, caterpillars can make sounds. Check out some of the videos from Dr. Yack’s research lab here which show caterpillars making their sounds.

- Why are the butterflies so seemingly random in their flight patterns? Not straight from A-B?

-

I understand the answer to be two reasons. First, the seemingly ‘random’ flight pattern serves to make butterflies more challenging to catch on the wing by avian predators (and human butterfly enthusiasts). Second, from an aerodynamics perspective, butterflies are insects that don’t possess much mass and their large wings produce lots of lift and make them susceptible to wind gusts and the like. Perhaps the term ‘random’ is misleading because if their flight path was truly random they would not be very effective at arriving at their destination! – Dr. Jeff Dawson

- What’s the difference between a cocoon and a chrysalis?

-

All insects that have complete metamorphosis—butterflies, moths, beetles, flies, bees and wasps—go through a stage called the “pupa” (plural: “pupae”, pronounced “pew-pee”), in which their body plan is completely reorganized. In butterflies, the pupa has a special name: the “chrysalis”. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the word chrysalis comes from the Greek chrȳsós, meaning gold, referring to the metallic sheen of some butterfly pupae. Also according Merriam-Webster, the term chrysalis can be used for moth pupae, although this is uncommon in practice.

In many moth species, but not in butterflies, the larvae form a “cocoon” around themselves just before they pupate. The cocoon is made of silk, which the larvae produce in glands in the mouth. The silk we use for clothing comes from the beautiful pure white silk of the domestic silk moth (shown below). Caterpillars of many species incorporate leaves or soil into their cocoons. The cocoon hides the pupa (see the well camouflaged luna moth cocoon, below) and protects it from predators and parasitoids. Still, almost every moth species has some specialized natural enemy that has evolved the capacity to find and attack the pupa despite the presence of a cocoon. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- Why do butterflies have colourful wings?

-

They have colorful wings to warn predators that they are poisonous and to attract a mate. – Greenhouse Manager, Ed Bruggink

- Why do butterflies fly?

-

Butterflies fly to find mates and female butterflies fly to find plants that their caterpillars can feed on. They also fly to avoid being eaten by predators, such as birds. Flying takes energy, so they also fly from flower to flower to get more “fuel” to power their flight.

Butterflies are beautiful, but their close relatives, the moths, have much more diverse and interesting lifestyles. All butterflies can fly, but the females of some moth species have lost their ability to fly and some even have little bitty wings that are useless! Instead of putting their energy into growing wings and flight muscles, they make thousands of eggs. They have traded the ability to fly to be super-moms. This only works if their offspring’s food plants are easy to find, like big trees.

Butterfly caterpillars often feed on host plants that are too small to support more than a couple of caterpillars and that are hard to find and scattered throughout the landscape. Butterfly females need to be strong fliers to find those plants and make sure they lay all their eggs during their 2-3 week adult lifespan. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- How do you not scare the butterflies when you bring them here?

-

The butterflies in Carleton’s Butterfly Show come to Canada while they are in the pupae phase of their lifecycle. This is a resting stage where they are transforming into butterflies. Once they arrive to Carleton, the pupae are put in the nursery where they emerge as butterflies before being moved into the greenhouse. Check out this video to see our Greenhouse Manager, Ed Bruggink, unpack a shipment of pupae received for the show: https://carleton.ca/biology/annual-butterfly-show/who/.

- How do butterflies evolve from the cocoon?

-

This is a good question, because it is so hard to imagine how a butterfly that is all cramped and folded in its chrysalis manages to emerge. First of all, though, let’s make sure we’re using the right words since vocabulary is very important in science. When insects change from their larval form (for example, a caterpillar) to the adult form (for example, a butterfly) they form a “pupa”. In butterflies, we use a special word: “chrysalis”. For moths, it’s just “pupa”. Many moths go an extra step and cover their pupa with a cocoon. The cocoon can be made of just silk, produced by glands in the caterpillar’s mouth, or the silk can be used to tie leaves or chunks of soil together. Butterflies do not make cocoons for this extra layer of protection.

There are two words we use for describing an adult insect coming out of the pupa: “emergence” and “eclosion” (French for “hatching”). If you use the word “eclosion”, everyone will know you are a real “entomologist” (a scientist who studies insects). The term “evolution” is best left for things like birds evolving from a type of dinosaur.

Getting back to the chrysalis, when the butterfly is ready to eclose, the outer skin starts to soften and the butterfly flexes its muscles to make the skin split, so that it can get its legs out. Then it pulls the rest of the body out. At this point, the wings are all crumpled, and the body is short and plump. The butterfly pumps fluid into the wing veins, which helps them to expand. Once the wings are dried and hardened, excess fluid, called “meconium” is excreted. This “butterfly poop” is usually a very bright yellow, orange, pink or red. The butterfly has one more task before it flies: it needs to assemble its proboscis, the long, coiled straw it uses to feed on nectar. When a butterfly first emerges, its proboscis is split into two coils. After repeatedly coiling and uncoiling the proboscis, the two halves eventually zip together. Once it has working mouthparts and dry wings, and has pooped out the meconium, it is ready to fly. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- Why do caterpillars eat leaves, then go into a chrysalis, then grow wings and then become a butterfly?

-

That’s a very good question, but one that is complicated to answer. All of these things–caterpillars eating leaves, the formation of the chrysalis and the emergence of the winged adult butterfly–have evolved over millions of years because those characteristics made the individuals that have them very successful.

Take eating leaves, for example. Leaves are not particularly nutritious if that’s all you eat. They are tough, they contain very little protein and they sometimes contain nasty chemicals. However, the first insects that were able to survive off a diet of just leaves had this food almost entirely to themselves, and they became quite successful. Over millions of years, they evolved into the hundreds of thousands of species of butterflies, moths and beetles that we know today.

The butterfly and moth life cycle–egg, caterpillar, pupa (chrysalis), winged adult–is also a strategy that is very successful. Caterpillars concentrate on feeding and growing. The simple caterpillar shape (sort of pool-noodle shaped) is the most efficient shape for growing fast and molting several times to get bigger. The winged adult is the most efficient form for finding a mate and, for the females, for searching for host plants to lay eggs on. These things together make the Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) hugely successful, and have led to the amazing diversity of species that we see today. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- What do caterpillars eat?

-

Almost all caterpillars feed on plants and most plant-feeding caterpillars feed on leaves, which are the most abundant and accessible part of the plant. However, there are some that burrow into stems, and others, called leaf-miners, that live between the top and bottom membranes of a leaf (the adults of these caterpillars are very tiny moths). A few caterpillar species prefer to eat flower petals, and there’s even one that decorates itself with the petals for camouflage (see the below photos).

Even more bizarre are the caterpillars that eat meat. Yes, that’s right: some caterpillars are carnivores! Here is a link to a video of a Hawaiian inchworm caterpillar catching and eating a fly! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAiMzeOfOgA

And in case you think that sort of thing can only happen in exotic, tropical places like Hawaii, here’s a local example of a carnivorous caterpillar. The caterpillar of the harvester butterfly lives among wooly aphids on alder trees, uses their “wool” (which is actually made of wax) for a disguise, and eats them! Harvester butterflies can be seen in Ottawa in the Mer Bleue sector of the Greenbelt. https://uwm.edu/field-station/harvester-butterfly/ – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- Do butterflies use a nest?

-

Butterflies do not have a nest in the sense that birds have a nest, where the parents sit on the eggs until they hatch and then take care of the babies. Butterfly mothers carefully choose a plant for their caterpillars to eat, but they do not stick around to take care of their offspring.

However, some caterpillars do live in a sort of nest. It is a tent that they make themselves, by tying leaves together with silk, which they produce from glands in their mouth. It takes many caterpillars working together to build the nest, so this behaviour is only seen in some butterfly species where the mother lays large batches of eggs on a single plant. The tent protects the caterpillars from predators. In Ottawa, Baltimore Checkerspot caterpillars make a tent on their food plant, white turtlehead. (The picture was taken along a trail in the Greenbelt.) – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- How long is the average Butterfly life?

-

This question is actually more complicated than it might sound at first. Strictly speaking, an individual butterfly’s life also includes its time in the egg, caterpillar and pupal (chrysalis) stages, not just the adult stage. For species with one generation per year that are dormant in the cold months, that would mean that a single individual can live for a year.

If you are thinking of just the adult stage, the lifespan can vary enormously, even in the same species. For any species that has two generations per year and overwinters as an adult, the overwintering adults live for 10-11 months, while the “summer” generation adults may live for only 2-3 weeks. The mourning cloak (photo below) is a good example of a butterfly species that has two generations in parts of its range and overwinters as an adult.

Then there is the issue of how long they can live (for example, in the lab, with appropriate temperatures and abundant food) versus how long they actually do live in nature, where they are subject to inclement weather and predators. I can pamper an old butterfly and keep it going for a month in the lab, whereas it might have lived only a week or two in the wild. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Take a closer look at the Butterfly Life Stages described in the Butterfly Educational Posters on our Learning at Home page.

- What is the smallest butterfly?

-

Here is the smallest butterfly in the world. I saw it last spring at the Burnt Lands Alvar Provincial Park. The strawberry flower it is sitting on is pretty close to the size of a dime. All of the butterflies in the family Lycaenidae (Blues, Coppers and Hairstreaks) are pretty small. The smallest on record is the Western Pygmy Blue. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Western Pygmy Blue, native to the western U.S. has a wingspan of 12-20mm

- Why are butterflies called Butterflies?

-

This is a great question, one I probably should have looked up long ago! I always assumed it was because of the common sulfur butterflies, which are a buttery yellow colour. It turns out that’s just one possibility for the origin of the name. Here are some others:

Butterflies might be named for the colour of their excrement. Old Dutch had the term “boterschijte”, which literally means “butter $#!t” (trying to keep this family friendly!) When butterflies metamorphose, their first poop upon emerging from the chrysalis, called “meconium”, is brightly coloured, often yellow or orange.

Old German names included “botterlicker” (butter-licker), “molkendieb” whey-thief and “milchdieb” (milk-thief). It has been suggested that people in the middle ages believed that butterflies stole milk and butter. This makes me want to do an experiment! Looking to supplement their diet with minerals, butterflies will feed on lots of weird things, including urine, feces and dead animals. I wouldn’t be surprised if you could get them to come to a puddle of discarded whey or an old rotting cheese rind. I’ve got to try that! Back in the Middle Ages, when dairy products were made in the barnyard, it is possible that butterflies snacking on discarded dairy products gave rise to these names.

The tendency for butterflies to feed on poop might also explain the Old Dutch term. Butter-coloured sulfur butterflies feeding together on animal excrement might have given rise to the name.

The possibilities are delightful, aren’t they?! Below is a question mark butterfly (note the white question mark on its wing) feeding on nice fresh doggy doo on a trail in the Ottawa Greenbelt. You’re welcome! – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Source: https://wordhistories.net/2017/11/25/names-of-butterfly/

- Do the butterflies that eat poisonous stuff have poison in them?

-

Butterflies that eat toxic (poisonous) plants while they are caterpillars have many different adaptations for dealing with plant toxins.

Some butterflies keep the toxins in their bodies to protect themselves against predators while they are still caterpillars and retain these toxins when they metamorphose into adults. They sometimes store the plant toxins in specific parts of the body. Monarchs have toxins that they get from eating milkweed in their wings. A bird that takes a bite out of the wing learns that the monarch is not good to eat, and the monarch survives to fly another day, although perhaps not as effortlessly as it would have with undamaged wings.

Other caterpillars that eat toxic plants do not store the toxins in their bodies. They have enzymes in their guts that detoxify the toxins just as we do (our enzymes are mainly in the liver). If they have just eaten, however, their foregut (the first gut segment) might be full of nasty plant juices that they can regurgitate onto predators that try to eat them.

One of my favourite examples of dealing with plant toxins comes from the tobacco hornworm, which is the caterpillar of a large moth. Nicotine in tobacco is highly toxic to most organisms (including humans). Tobacco hornworms “breathe” nicotine out of their spiracles, which are tiny holes on the sides of their bodies that they use to take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide, like our nostrils. Having stinky “nicotine breath” protects the caterpillars from predators such as spiders. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- Are the wasps in my garden keeping butterflies away?

-

While it is possible that some pollinators are aggressive towards each other, I am amazed at how often I see the opposite: butterflies, bees, wasps and other pollinators “getting along” together on nectar sources. One exception to that is the native solitary bees that have territorial males, which can be aggressive in a sort of cute way. I’ve seen them try to bonk a bumblebee off a flower. However, most large wasps have little incentive to be aggressive at flowers. Wasps are mainly meat eaters, either as predators or parasitoids. When we see them at flowers, they are mostly stopping to re-fuel so that they have the energy to search for caterpillars, spiders and other soft-bodied insects. Although the wasps that live in large nests will aggressively defend the nest, there isn’t much reason for them to be aggressive towards other insects, such as butterflies, at flowers. However, it is possible that their huge appetite for caterpillars might be having an impact on the numbers of butterflies in your yard.

Another reason for the decline that you observed is that butterfly numbers can fluctuate greatly from one year to the next. Some years are better than others for monarchs (I wasn’t sure if you were seeing a decline in the numbers of this particular species or if it was a dip in the numbers of butterflies in general you had noticed). Red admirals are one of the best examples of the natural variability in butterfly abundance; their numbers can fluctuate from one year to the next by orders of magnitude. These natural fluctuations could be behind your observation of fewer butterflies this past summer. We also had drought conditions in June and July which could have affected butterfly numbers later in the summer by drying out the host plants of the early-season caterpillars. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

- How do butterflies fly?

-

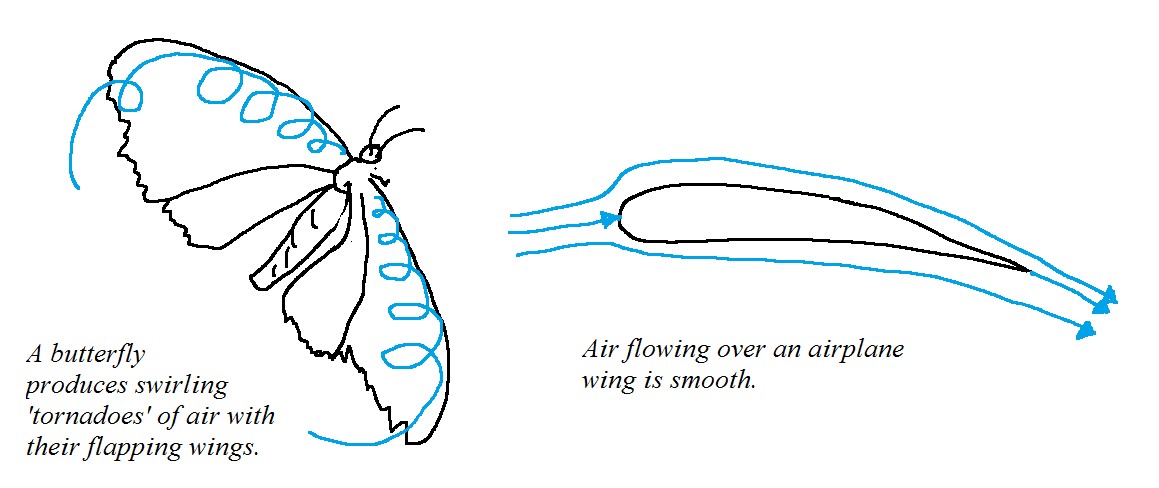

This is a great question – in fact, it’s a question that has motivated my entire professional career! Now, I’m going to assume you’re asking about the aerodynamics of flying, not how the muscles move the wings up and down. The answer to this question is actually something that we’re only recently (in the last c. 20 years) beginning to understand. Butterflies DO NOT fly like airplanes or birds – they do it differently! Butterflies produce lift, which is the force that keeps butterflies in the air, using small swirling vortices (‘tornadoes’) of air they generate with their wings as they flap them up and down! Producing lift the way airplanes produce lift simply doesn’t work when you’re as small as a butterfly. In fact, butterflies, moths, and other flying insects all seem to use the same or similar ‘tricks’ to keep in the air. It’s a very exciting time to study how insects, like butterflies, fly – in fact, what we’re learning about how insects fly is also helping us with making better flying machines like drones and microaerial vehicles. – Dr. Jeff Dawson

To further explain this complicated subject to a younger audience, Dr. Jeff Dawson created this video and the below image.

Butterflies have well developed wings that they use to escape from predators and find mates. They have strong flight muscles that allow them to fly in zig-zaggy directions to outsmart a bird that might be chasing them. Most butterflies have legs that they use for walking on plants, for example when they are laying eggs. I have never seen a butterfly running. Flying is their mode of transportation when they want to get somewhere quickly. – Dr. Jayne Yack

- How do butterflies adapt to their environment?

-

Butterflies have many different adaptations to find mates, avoid freezing and avoid predators. For example, Monarch butterflies from Canada fly thousands of miles to Mexico to avoid the freezing temperatures during the winter. Some butterflies flick their wings to display eyespots, and ooze nasty foam from their bodies to stop the attack of a predator. – Dr. Jayne Yack

- Do butterflies really taste through their feet?

-

Many insects, including butterflies, have contact chemoreceptors on their legs. They can also taste with sensory organs on their mouth parts. Insects have sensory organs on different parts of their bodies. Some butterflies can ‘see’ with their back ends, and ‘hear’ with their wings. – Dr. Jayne Yack

Taste involves detecting chemicals upon contact or “contact chemoreception”. Butterflies do indeed have contact chemoreceptors on their feet, so yes, they “taste” plant chemicals through their feet, just as we use the receptors on our tongue to taste our food. However, a female butterfly doesn’t taste the plant leaves because she is interested in eating them herself. Her main concern is finding an appropriate plant for her offspring to feed on. She needs to detect the right combination of chemicals on a leaf to determine whether that plant is safe (not toxic) for her caterpillars before she lays an egg. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Butterflies have chemoreceptors on their feet that act like human taste buds. A female butterfly will drum the leaves with her feet to release the plant juices. She is searching for the right plant chemicals and if it is a match will lay her eggs. These chemoreceptors sense dissolved sugars in fermenting fruit. A favorite snack for tropical butterflies. – Greenhouse Manager, Ed Bruggink

Yes — it’s true. Many insects ‘taste’ with strange parts of their bodies in comparison to how people (i.e. humans) taste (and smell) things — we use our mouth and nose. Taste (and smell) is essentially a process of detecting molecules in the environment and sending messages to the ‘brain’ for processing. Butterflies have receptors on their feet that detect molecules in their environment — basically, detecting the molecules of/in what they are standing on. Ditto for their antenna detecting molecules wafting along in the air (like pheromones). Is taste to a butterfly the same as taste to a human? Well… what is perceived depends on how the butterfly interprets the messages arriving at it’s brain. Clearly a butterfly brain is different than a human brain so it’s very unlikely that both humans and butterflies ‘perceive’ the deliciousness of an orange slice in the same way. – Dr. Jeff Dawson

Visit our Instagram page, @cuButterflies, for more facts!

- What plants can I put in the garden at home to attract butterflies?

-

To attract butterflies to your yard, you need to provide the two things they are looking for: a source of nectar and, for the females, the appropriate host plant on which to lay eggs.

The best nectar plants are those that also serve as a host plant for butterflies–milkweed comes to mind as a good nectar plant that is also a host plant for the monarch butterfly. Unfortunately, there are not many plants that do this sort of double-duty. Many good native nectar plants do not host a local butterfly species, but they do host moths and other insects and thus play an important role in the ecosystem.

For example, goldenrod is an excellent nectar plant. While it doesn’t host any butterflies, hundreds of native insects feed on it, which in turn provide food for birds and other wildlife. Asters (several species) also provide a good late-season source of nectar. Early nectar sources include cherry, apple and crabapple trees. A closely related species that is also native is shadbush (= serviceberry, saskatoon). Wild bergamot, bee balm and blazing star are gorgeous mid-season nectar plants.

Butterflies will also use rotting fruit as a source of sugar. The mourning cloak butterfly, which is one of the earliest species to be seen in spring, feed on tree sap, and can often be seen feeding from the holes made by yellow-bellied sapsuckers.

The host plants that serve as food for the caterpillars of Ontario butterflies are not necessarily beautiful flowering plants that you would typically see in a garden. Here are some of my favourites:

- Stinging nettle: attracts red admirals and comma butterflies, in huge numbers in some years

- Thistles: attract the painted lady butterfly (avoid the so-called Canada thistle, which is not Canadian, and which is an invasive spreader. Go with bull thistle instead.)

- Hop tree and prickly ash: for the giant swallowtail

- Dill and fennel: for black swallowtails

- Hackberry: question mark butterfly

- White turtlehead: Baltimore checkerspot

- Chokecherry: tiger swallowtail

- Do butterflies have ears?

-

Insects have many different types of ears all over their bodies. Many butterflies have ears at the bases of their front wings. We think they use them to hear bird predators. Some butterflies that fly at night use their ears to detect hunting bats. Some butterflies have ‘hearing aids’ on their wings to amplify sounds that are important to them. – Dr. Jayne Yack

- Could different types of butterflies breed with one another to make a new species?

-

Yes, individuals from two separate species occasionally mate and form hybrid offspring. Typically, this occurs between species that are very closely related. A good North American example is a population of swallowtail butterflies in upstate New York that appeared for the first time late in the summer in 1999. Genetic analysis has shown that these butterflies are a hybrid of the Canadian tiger swallowtail and the Eastern tiger swallowtail. Because they emerge late in the season, the new population is reproductively isolated from the parental populations which emerge early in summer. Presently, they can still mate with the parental species and produce healthy offspring in the lab. However, if the reproductive isolation persists for many years, over time the hybrid population will accumulate genetic differences from the two parental species, and possibly become a separate species. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Source: Ording, G.J. et al. 2010. Allochronic isolation and incipient hybrid speciation in tiger swallowtail butterflies. Oecologia 162:523-531

- Do butterflies sleep? Can they dream like humans? What do you think they would dream about?

-

Several insect species, including bees, fruit flies and cockroaches, have been demonstrated to sleep, so it’s probably safe to assume that butterflies do, too. How do we know that insects sleep? Butterflies and other insects cannot close their eyes when they sleep, because they do not have eyelids. However, they do enter a typical “sleep posture”. For example, some native bees spend the night on a plant stem, holding on with just their mouthparts. While asleep, their eyes do not respond to moving images the way they would during the day when they are awake.

More importantly, sleep in insects is necessary to “recharge their batteries” just like it is for us. If they are deprived of sleep, they are less alert, and will sleep in late the next time they get the chance. Sleep-deprived insects have memory issues, just like students who have pulled an all-nighter cramming for an exam.

As to whether they dream, and what they dream about, we can only guess. I would like to think that butterflies dream about warm sunny days in fields full of flowers and plants to lay eggs on. I certainly hope they do not have nightmares about entomologists chasing them with a net!

Source: Helfrich-Forster, C. 2018. Sleep in insects. Annual Review of Entomology 63:69–86

- What do you do with them when they die?

-

The butterflies that are a part of Carleton’s Butterfly Show live out their natural lives in the greenhouse. Since these are tropical butterflies when they die we have to collect the dead ones and they cannot leave the research building unless they are disposed of safely. – Greenhouse Manager, Ed Bruggink

- Has it been established how the three phases of a butterflies life evolved. Many years ago I saw an article suggesting that it was due to an accidental merging of a caterpillar like animal with a flying insect and the flying insects DNA eventually emerged from the caterpillar via the pupa.

-

Thank you for this fascinating question. Let me first provide a little background for readers unaware of where this curious hypothesis came from. In 2009, a highly prestigious journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), published a short communication written by Donald Williamson, a marine biologist at the University of Liverpool. Williamson proposed that a hybridization event between organisms very different in form—a velvet worm (see image below) and an unknown winged insect—gave rise to the Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) and other insects that have caterpillar or grub-like larvae and a winged adult. Williamson did not provide any evidence that such an event might have happened, but he did propose that a look at the length of the lepidopteran genome might support his idea: the Lepidoptera would be expected to have an extra large genome, consisting of insect genes that determine adult form, as well as velvet worm genes that code for larval form. He also suggested that researchers with access to velvet worms try to inseminate a cockroach with velvet worm sperm.

As a “communication” in PNAS, Williamson’s paper did not have to go through the usual peer review process. Instead, it was accepted for publication by an editor, Lynn Margulis, who is renowned for her “endosymbiont theory”, in which early bacterial cells engulfing smaller cells gave rise to more complex organisms and ultimately led to the evolution of plants, fungi and animals. She endured years of criticism for her unorthodox idea before it was finally accepted by the scientific community, an experience that probably led her to be sympathetic to Williamson’s fringe idea. Nevertheless, peer review is an important part of weeding out ideas that can be easily debunked, as was the case for Williamson’s hypothesis. (PNAS has since eliminated the “communication” route to publication.)

At the time of publication, there were already enough studies on genome size in the literature to test Williamson’s hypothesis, as Michael Hart of Simon Fraser University and Richard Grosberg of U.C.Davis pointed out in a quick rebuttal. Insects with caterpillars or grubs do not have more genes than either insects without a larval stage or velvet worms. Moreover, butterflies do not have a set of genes that closely resemble those of velvet worms. In terms of genetic similarity, insects with larvae are most closely related to insects without larvae, and the insects as a whole are more closely related to the other arthropods (spiders, mites, crustaceans, etc.) than they are to velvet worms.

The difference between adult butterflies and their caterpillars is indeed astounding, as is the complete restructuring of the body plan during metamorphosis. However, the larval stage can be explained by natural selection acting upon the juveniles and shaping, through evolution, a form that best accomplishes quick growth and accumulation of the energy resources that the adult will need to disperse and reproduce. Soft bodies and cylindrical shape have been proposed as the best way to grow quickly when constrained by an external skeleton that needs to be periodically shed to allow growth. – Dr. Naomi Cappuccino

Sources:

Williamson, D. I. 2009. Williamson DI (2009) Caterpillars evolved from onychophorans by hybridogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:15786–15790.

Hart, M. W. and Grosberg, R. K. 2009. Caterpillars did not evolve from onychophorans by hybridogenesis. PNAS 106: 19906–19909.

Maddrell, S. H. P. 2018. How the simple shape and soft body of the larvae might explain the success of endopterygote insects. J. Expt Biol 221

Velvet worm photo: Geoff Gallice on Wikimedia Commons

Share: Twitter, Facebook

Short URL:

https://carleton.ca/biology/?p=9625