Corporate Social Responsibility and Economic Sanctions: The Case of Latvia’s Information and Communication Technology Sector

By Jēkabs Kārlis Rasnačs, PhD student at the University of Latvia

July 24, 2025

Amid the ongoing war in Ukraine, Latvia is increasingly confronting the issue of companies using third countries to evade international sanctions. Many companies, particularly in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, use transit jurisdictions, undermining international efforts and national security. Traditional sanctions alone are insufficient, as individuals can easily re-establish businesses under new legal entities and beneficial owners. This memo explores the potential of corporate self-regulation through corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a proactive alternative.

CSR allows companies to voluntarily exclude themselves from unethical practices, ensuring that each employee takes responsibility for compliance with established norms. Participation in such ethical business practices could enhance corporate reputation and brand recognition. This issue is particularly pressing as the circumvention of sanctions continues to finance Russia’s war against Ukraine, making it a matter of national security. While the circumvention of sanctions occurs across various industries, this paper focuses on the self-regulation mechanisms implemented by Latvian ICT companies. An assessment of Latvia’s five largest ICT companies shows considerable variation in their compliance with self-regulatory standards. Only a few meet most criteria, likely because prior reputational issues have prompted greater efforts. Key gaps include: weak public advocacy, limited third-party transparency, and insufficient training on sanctions compliance.

This memo concludes that self-regulation practices concerning sanctions compliance among Latvian ICT companies are insufficient, especially in light of the war in Ukraine. Recommendations include encouraging CSR-based compliance frameworks, improving transparency, and considering a legal model similar to the United Kingdom (UK) Bribery Act 2010 to promote ethical business conduct and accountability. As sanctions circumvention directly impacts Latvia’s economic security and geopolitical independence from Russia and Belarus, promoting stronger self-regulatory and legal mechanisms are essential. This approach could also be applied to other high-risk sectors such as construction and extractive industries.

The Problem

The issue of sanctions circumvention, particularly through third countries, has become acute since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Data indicates that many Latvian companies use states in Caucasus and Central Asia as intermediaries to get around international sanctions. For example, in 2024 the Deputy Director of the Customs Administration – without disclosing the names of specific companies – noted a sharp increase in the number of sanctions violations committed by Lativan companies. The export of goods was prohibited in more than 2,900 cases, with 63% of the violations related specifically to Central Asian countries. This report highlighted that the goods being intercepted are mostly various mechanical devices, vehicles, and electrical equipment. Similar increases have been observed in Germany, as reported in a commentary by Robin Brooks. There is extensive discussion about the need for sanctions against companies that facilitate such activities. However, it is evident that this approach is not sustainable, as it often fails to address the root problem, namely, that the same individuals can establish new legal entities, continue their operations under a different owner, or employ alternative schemes to circumvent restrictions.

The Context

In the case of CSR, compliance with economic sanctions is not a well-documented subject. According to relevant literature on the topic, sanctions compliance could be indirectly linked with topics, such as political involvement; corruption risks associated with third party involvement; as well as public anti-corruption stances. CSR is also generally accompanied by an applicable compliance framework that aids in internalizing and implementing its provisions, as well as adhering to its own established standards and norms. Furthermore, the literature emphasizes the necessity of a proactive and innovative approach in developing supplementary mechanisms that facilitate the enforcement of legal norms beyond mere regulatory compliance.

There are related but not directly addressed topics about sanctions compliance within CSR. In 2025, the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights released a statement implying that businesses should comply with all relevant legal frameworks, which could include sanctions. Maayan Menashe argues that international standards can become embedded as social norms within corporations, influencing their behaviour even when legal enforcement is weak or absent. Similarly, sanctions compliance can be reinforced by market and societal expectations, making circumvention more reputationally and financially costly. According to Hortense Jongen, the private sector is facing pressure to comply with international standards, particularly in areas like anti-bribery and corporate responsibility, because of scrutiny from investors. Just as firms voluntarily align their CSR policies with international standards to maintain credibility, according to Bryan R. Early and Timothy M. Peterson, they may also adopt stricter compliance policies regarding sanctions to avoid being blacklisted or excluded from markets. A strong example of corporate response to geopolitical events is the reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with over 1,000 companies publicly announcing the curtailing of operations in Russia beyond the minimum legal requirements imposed by international sanctions.

A recent study by Keith A. Preble and Bryan R. Early claims that a critical aspect of compliance with economic sanctions is the reputational risk faced by businesses, with enforcement agencies leveraging “naming and shaming” tactics to deter violations. Firms fearing reputational damage are less likely to engage in risky transactions with sanctioned entities, and the heightened scrutiny on large corporations creates industry-wide compliance pressures. However, the authors also highlight the disparity in penalties between domestic and foreign firms, with American institutions imposing significantly higher fines on foreign entities to ensure global compliance. Similar conclusions come from a study which examines firms’ strategic responses to sanctions, particularly those imposed on Russia after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, through a survey of 610 medium-sized companies in Germany, Poland, and the United States (US). This analysis finds that, while external pressure generally encourages compliance and even overcompliance, it can also push some firms toward sanctions circumvention. Compliance is often accompanied by proactive business strategies aimed at finding legal loopholes to continue operations. The results of this study underscore the variation in corporate responses based on national regulatory environments – US firms, for instance, face stronger legal enforcement mechanisms, whereas firms located in the European Union (EU) , particularly in Germany and Poland, exhibit a wider spectrum of compliance behaviors. These findings suggest the need for stronger enforcement mechanisms, standardized regulatory guidance, and targeted measures to curb both undercompliance and sanctions circumvention.

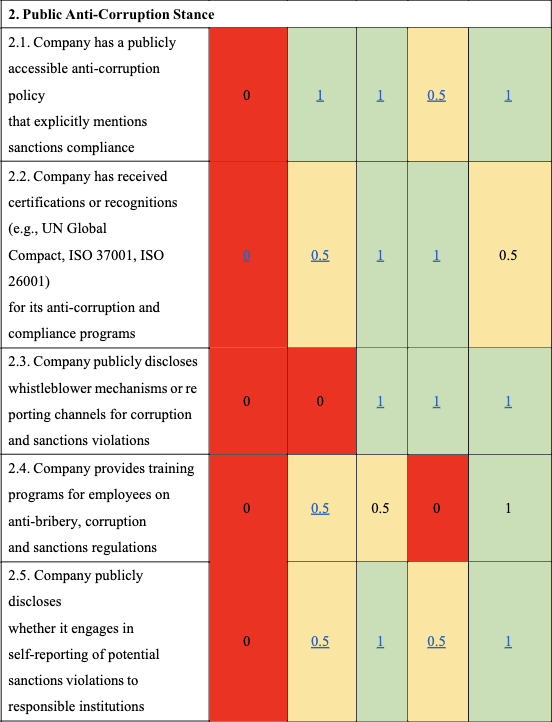

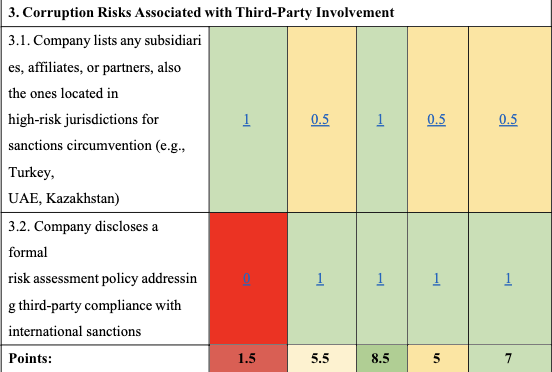

To gain insight into how such regulatory measures are implemented by Latvian ICT companies and what the most popular approaches are, this memo examines the largest ICT enterprise, including a review of corporate statutes, annual reports, as well as open and publicly available data. The evaluation is conducted based on criteria aligned with international standards. However, the criteria used in this memo are modified to reflect the existing narrative on sanctions circumvention, specifically addressing political involvement, corruption risks associated with third-party involvement, and public anti-corruption stance. The assessment is conducted based on a scoring system, where “Yes” is assigned 1 point, “Partially” is assigned 0.5 points, and “No” is assigned 0 points, depending on the extent to which the information found in the company’s documentation aligns with the methodological criteria.

The methodology to review the most popular approaches is based on ISO 37001 (Section A.10 Due diligence), ISO 26001 standards (Subject of fair operating practices), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 205: Anti-corruption 2016 standards (training programs), ICGN Guidance on Anti-Corruption Practices (third-party involvement and whistle-blowing) and Transparency International and World Economic Forum toolkit about Business Integrity (sanctions compliance and restricted parties). State-owned companies or companies that have previously been state-owned are excluded from the study. Primarily, publicly available information about companies is included, and letters requesting answers to specific questions were sent out to relevant companies as a secondary source.

Table No.1 Criteria to review most popular self-regulatory approaches

| Criteria | 1 point | 0.5 points | 0 points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. | Company reports meetings on internally created file or register where high-level or medium-level employees have to report any meetings/consultations with government officials | Only selected reports can be found on social media or company website | None |

| 1.2. | Company has written its sanctions compliance on statutes, annual reports, open, and publicly available data | High-level employees of the company have publicly acknowledged sanctions compliance | None |

| 1.3. | Industry association membership is disclosed on website or publicly available documentations | Industry association membership is disclosed on request or can be found elsewhere on the Internet (e.g. website) | None |

| 2.1. | Company has publicly accessible anti-corruption policy that mentions sanctions compliance | Company does have anti-corruption policy without mentioning sanctions compliance and/or the policy document is accessible only on request | None |

| 2.2. | Company has received any certificates on anti-corruption and compliance programs (e.g. TRACE, ISO 37001, ISO 26001, Wolfsberg AML Certification) | There are other industry-related certificate/s received (e.g. eCOGRA for gambling, ISO 27001 for information security in ICT companies) | None |

| 2.3. | Whistle-blowing mechanisms or reporting channels are present both externally and internally | Channels exist only internally | None |

| 2.4. | The training programs focus on both topics (anti-bribery and corruption compliance, sanctions regulations) | The focus is only partial (e.g., training programs exist for anti-bribery and anti-corruption compliance, but not on sanctions regulations). | None |

| 2.5. | Self-reporting channel on the website has a public disclaimer that the company engages in reporting potential sanctions violations to responsible institutions (e.g. Financial Intelligence Unit) | Such information is available elsewhere on the webpage but not under the reporting channel | None |

| 3.1. | Company discloses full list of its subsidiaries, affiliates, or partners. | Company only partially discloses its subsidiaries, affiliates, or partners, and that extended information is available through enterprise and beneficial owner registries | No information about subsidiaries, affiliates, or partners is available on company website |

| 3.2. | Company has publicly available risk assessment policy paper addressing third-party compliance with international sanctions | Such policy paper is available internally in the company | None exist |

Table No.2 Evaluation of the largest Latvian ICT companies

Overall, self-regulatory approaches and their implementation among the five largest Latvian ICT companies can be characterized as insufficient according to the utilized methodologies. There are significant disparities in the extent to which companies comply with the requirements, with some demonstrating full or near-full compliance, while others fail to comply with any of them.

The lowest performance was observed in areas such as advocacy for sanctions compliance, transparency regarding meetings with public authorities, and disclosure of industry association memberships. In addition, most companies disclose only their own offices and a limited number of partners, failing to provide comprehensive disclosure of partners across different jurisdictions. Furthermore, there is insufficient recognition of anti-corruption and anti-bribery compliance programmes, and whistleblowing mechanisms for employees are largely absent. Additionally, based on the analysis of social media and website content, as well as information obtained through formal correspondence, existing training programmes appear to inadequately cover all key topics. Typically, employees across all levels receive uniform training content on anti-corruption and compliance, with no specific reference to sanctions compliance.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Given the inconsistent approaches among businesses in implementing sanctions compliance policies, it may be beneficial to consider a legal framework similar to the UK’s Bribery Act 2010. This legislation has motivated both domestic and foreign companies operating in the UK to establish adequate procedures for preventing bribery, as failure to do so may result in legal liability. A comparable framework could be developed for sanctions compliance in Latvia – clearly defining what constitutes a sanctions violation and establishing enforcement mechanisms. Such a framework should also include provisions for holding companies accountable for failing to prevent sanctions circumvention or violations.

At the same time, such measures may be considered controversial, as critics might claim that these regulations limit companies’ ability to compete and expand internationally, potentially undermining short-term competitiveness. Criticism of this regulatory framework often comes from proponents of reduced mandatory requirements and various private sector actors – particularly those operating in high-risk jurisdictions where law enforcement institutions are less advanced. In such contexts, companies based in developed economies can exploit institutional weaknesses to serve their own interests. This issue underscores the broader phenomenon whereby business actors from developed countries ‘export corruption’ and take advantage of their cooperation partners in developing countries. To mitigate such practices, only a few jurisdictions have introduced specific regulations, for instance, foreign bribery committed by U.S. nationals or persons located in the country is addressed under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Analysis of ICT companies in Latvia reveals differing approaches to sanctions compliance. It is important to acknowledge that sanctions circumvention, much like bribery, undermines business environments, economies and national security in the long term, often involving tax avoidance, tax evasion, tax fraud, and money laundering. Given Latvia’s current focus on economic competitiveness and independence from Russia and Belarus, there is a strong case that implementing such a regulatory framework could positively influence corporate decision-making, especially in selecting international partners. The evaluation shows that only Tietoevry Latvia has largely met most criteria, likely as a result of efforts to restore its reputation following a recent bribery scandal involving Belarus. In other cases, the extent of compliance remains incomplete.

In sum, based on the analysis conducted, the following recommendations are proposed for Latvian policymakers and other relevant stakeholders:

1. Develop a comprehensive legal framework for sanctions compliance. It is recommended that policymakers establish a legal framework for sanctions compliance and prevention of foreign bribery, modelled on the UK’s Bribery Act 2010;

2. Promote enhanced corporate due diligence in partner selection. Companies should be encouraged to strengthen their due diligence practices, particularly when selecting international business partners, especially in high-risk geopolitical contexts;

3. Expand compliance evaluation to other high-risk sectors. It is advisable to apply the compliance evaluation methodology currently used in the ICT sector to other high-risk industries, including construction and extractive sectors.