Democracy Meets AI

Ilija Nikolic

When Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama joked that his new artificial intelligence (AI) “minister,” Diella (Albanian for Sun), was “pregnant with 83 children” (a metaphor for 83 digital assistants that will serve members of parliament), he turned an institutional reform into viral political theatre. The move to incorporate AI into governance itself is considered by many to be amusing, unsettling, and even revealing, as it shows how easily AI can be warped into a spectacle while subtly re-wiring how decisions about money and power are made. Diella is also the world’s first AI system formally appointed as Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, with responsibility for public procurement, one of Albania’s most corruption-sensitive sectors.

From Virtual Assistant to Cabinet-Level Minister

Diella was “born on January 19, 2025” as a virtual assistant on the e-Albania platform, intended to assist Albanian citizens in accessing documents and other online public services. Nine months later, in September 2025, following a decree that authorized a virtual minister, Rama had elevated Diella to the rank of Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, formally integrating an AI system into the Council of Ministers.

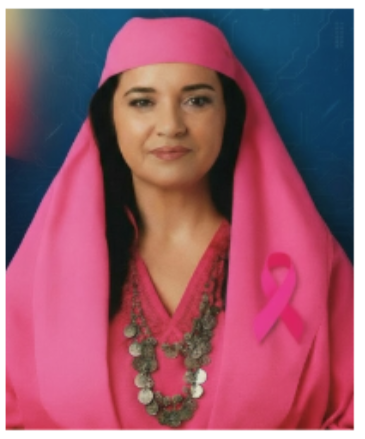

Such an unorthodox move has garnered plenty of international coverage, as many have framed it as both an anti-corruption experiment and a form of political branding, describing Diella as a digital assistant dressed in traditional clothing, now tasked with making public tenders free of corruption. However, some have also pointed out that procurement in Albania has long been dominated by political elites and oligarch-like figures, making Diella’s new role a crucial aspect of Albania’s EU-accession narrative and trajectory.

A Spectacle?

Writer/researcher Vera Tika calls Diella a case of “Avatar Democracy”: essentially shifting political responsibility to digital actors and presenting them as being pure, incorruptible, and tireless, standing in for distrusted political elites. Perhaps accidental, this comes across as not a neutral design choice. Presenting the system as a woman in traditional costume frames digitalization as care and service rather than control, pulling on gendered stereotypes while also making it difficult to contest the new political innovation without appearing as “anti-modern” or “anti-progress.” The “pregnancy with 83 children” metaphor pushes this further, casting Diella as a digital mother of dozens of subordinate systems that will monitor and help with parliamentary work. It infantilizes MPs as being dependent on an algorithm, and suggests that political conflict within parliament can be processed by a neutral machine rather than by openly accountable representatives.

The move to incorporate AI into governance sits at the intersection of EU accession politics and digital dependency, as Diella is likely based on OpenAI models hosted on Microsoft Azure, which is precisely the kind of foreign reliance that the EU is attempting to reduce. Hypothetically speaking, if Albania were to obtain EU membership and Diella were to operate within the EU, it would be flagged as a high-risk system under the new EU Artificial Intelligence Act, where stringent requirements are imposed on the usage of AI in public services and resource allocation. Such frameworks do not yet bind Albania; however, it is clearly experimenting in exactly the domain in which the Act targets, that being algorithmic governance, where constitutional accountability is thin.

Canada’s “Sovereign AI” Moment

Canada is moving quickly in a similar direction by embedding AI into state structures, but with a different approach. The Budget for 2025 announces $925.6 million over five years for “large-scale sovereign public AI infrastructure,” including a Sovereign Canadian Cloud to support research and public-sector AI use. The federal government is implementing AI and digital infrastructure as key elements of Canada’s nation-building strategy.

Canada already has a formal governance “toolkit” or framework for implementing public-sector AI. The government’s Directive on Automated Decision-Making and its official guidelines require “algorithmic impact assessments,” the formal documentation of the systems used, and alternative mechanisms for performing similar functions when automated decisions may potentially affect rights and interests. Moreover, the federal Digital Sovereignty Framework further defines sovereignty as the ability to manage and protect government data, systems, and infrastructure independently in a globally interconnected environment.

However, Canadian experts warn that infrastructure and branding risks could outpace efforts to control them. As noted by Heidi Tworek and Alicia Wanless, Canada’s dependence on American companies is one of the most significant risks and complications facing Canadian digital sovereignty, particularly given the dominance of US providers in digital and cloud services.

Put side by side, Albania and Canada reveal the same underlying question: who actually controls AI in the state, and under what rules? Diella is clearly an extreme case of AI as spectacle: an AI minister is “pregnant” with assistants, purity, and efficiency in a system still wrestling with corruption and weak checks. Whereas Canada’s “sovereign AI” push is more technocratic, but it faces its own temptation to treat big AI spending and a branded cloud as proof of control, even while key infrastructure and AI models remain under foreign corporate jurisdictions.

The core lesson for Canada is not to mock Diella, but to avoid a more subtle version of the same trap. As AI becomes more integrated into sectors that the federal government may deem appropriate, the real test will be whether such systems are contestable or even grounded in enforceable law, rather than merely marketed as innovative or sovereign, as it is easy to get caught up in the media storm and publicity such reforms seem to command. Canada’s task should be to ensure that its “sovereign AI” remains democratic, even when there is no digital “minister” on the screen.