The Origins of Exploring the Capital: An Architectural Guide to the City of Ottawa

by Nick Ward

Photography by Peter Coffman

Parliament Hill, The ByWard market, Centretown, Sandy Hill, Glebe, Old Ottawa South, Alta Vista, New Edinburgh, Rockcliffe Park and Vanier, Rideau Canal, The West End, Hull and the Chaudière, Nepean, and Beyond the Greenbelt…

How would you characterize the City of Ottawa?

Is Ottawa simply a sleepy government town, or is there much more to Canada’s capital city?

With their new book, Exploring the Capital: An Architectural Guide to the Ottawa Gatineau Region Carleton, writer and Carleton graduate Andrew Waldron (Adjunct Professor — History and Theory of Architecture) and photographer Peter Coffman (Associate Professor — History and Theory of Architecture) present a spirited case for the latter.

The author and photographer tell the story of Ottawa through the region’s magnificently diverse architecture and landmarks. In doing so, they weave a wonderfully complex account of Ottawa as a region where heritage coalesces with modern vigour.

Exploring the Capital takes readers through 12 guided tours of Ottawa’s vast green spaces and two fabled rivers, historic government buildings and houses of worship, cultural hubs and unique housing from century-old heritage homes to luxurious, sustainable condominiums. Through the guide’s adept storytelling and breathtaking photography, Waldron and Coffman provide literal roadmaps to a city whose notoriety might actually, and ironically, be obscured by its nuance. Exploring the Capital is a visual and verbal account of present day Ottawa which also provides historical context by tracing Ottawa’s character back to its origins, beginning with Queen Victoria’s decision to designate Ottawa as the nation’s capital, and the subsequent decision to opt for a neo-Gothic identity which concurrently embraced modernism and romanticism.

The rich story of Ottawa was one Coffman and Waldron were itching to tell.

“Every city is, of course unique, but I think what makes Ottawa exceptional is that it is a national capital, but still a rather small city with very humble origins,” said Coffman. “Our architecture manifests everything from grand visions of nation-building to a vibrant working-class history. The stories encoded in our built environment span this entire range.”

One of Waldron’s aspirations with the book was to surprise readers by featuring some of the city’s lesser known beauty. “If they ask me why a certain unknown place was included, I tell them that even unknown and less prominent places can be valued.”

A Romantic and Multi-Cultural City

“If there was one aspect of the area that is unique, it’s that it is much more romantic than people assume. Case in point, the Rideau River is still slightly wild and unlike the transportation rivers of other cities. This romanticism expresses itself in the three prehistoric and historic cultural layers—Indigenous, French, English.

Today, there is the multicultural layer. The city is much less identified by its Colonial past. Consider the presence of a Lebanese community in Ottawa since the early 20thcentury. How much research is out there on the Lebanese community?” Waldron asks.

[wide-image image=”23909″ /]

Rather than trying to wrangle the story of Ottawa into a singular, sweeping chronicle, Exploring the Capital presents the city’s character as comprising several unique identities. “Many voices would be unheard if I suggested there was a grand narrative to the region. The tours are enjoyably diverse to show how complex the region is,” says Waldron.

By avoiding a panoptic view of Ottawa, the guide does well through its 12 tours to demonstrate the conspicuous layers which Ottawans experience every day. For example, The National Capital Commission/Jacques Greber dimension of the city, which is essential to Ottawa’s identity, is presented in detail. As are the City Beautiful efforts of the early 20th century, which influenced many of Ottawa’s picturesque landscapes.

When asked about their personal relationships with the city, both Waldron and Coffman are quick to passionately describe in detail a myriad of Ottawa spaces and locations, but neither seemed very comfortable when pressed to choose just one or two of favourite locales.

“It’s impossible for me to pick one favourite place, but a number made a big impression on me,” says Coffman.

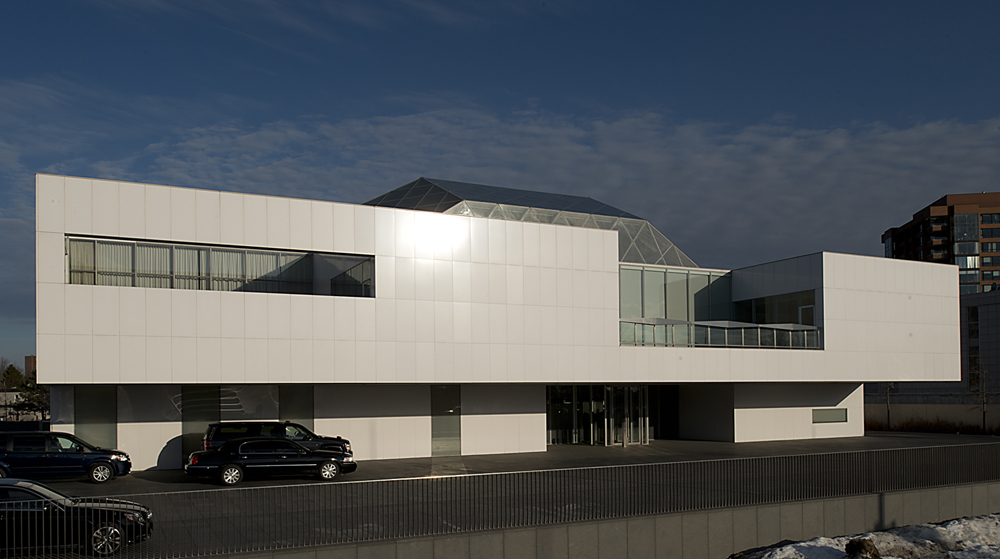

“I came away from working on the book with a new affection for the beleaguered Sparks Street, where the sunlight plays on an architectural quilt of fantastic variety. The Hart Massey House perches with beautiful delicacy among the trees and above the lake. The Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat is a breathtaking piece of architectural sculpture, inside and out.

[wide-image image=”23902″ /]

“My ‘favourite’ varies according to my mood; ask me ten times, and you’ll get ten different answers!”

Waldron was just as noncommittal as Coffman, but maintains that there are some spaces which he holds particularly dear. “I’m very fond of the Ismaili Centre, which is a very sensitive and special space that emerges from a challenging site. Architecturally, it embraces so many ideas and tendencies of the region.

Everyone tells me they love the building after they have visited it. There are also many modernist churches that are often underappreciated, mainly because church goers only attend their own denomination’s church and rarely visit other churches—and, of course, fewer people are worshipping in organized religion.

But, of course, there are so many favourites,” Waldron continues. “The original design of the National Arts Centre, some of the works of Jim Strutt, and the former Federal Study Centre on Heron Road have some fascinating spaces. I think I like every building in some way.”

One of the many superb functions of Exploring the Capital is that it provides readers with insight on some of Ottawa’s hidden gems. “There are so many,” says Coffman. “We tend to think of Gatineau as a place of tall government office blocks, but it has a marvellous historic core. Briarcliffe has an amazing group of architect designed modern houses set in what amounts to a forest. Britannia Village is a place that seems to belong to a distant rural area, but is contained within the capital city. Sullivan House and Strutt House are modest, but exquisite homes that two very accomplished architects—the former a student of Frank Lloyd Wright— designed for themselves. Ottawa is full of secrets that I hope will be less well-kept thanks to the book.”

Waldron continues Coffman’s train of thought: “I suppose some places are overlooked, such as Garden of the Provinces and Territories, which is one of my favourites. The Rockeries in Rockcliffe Park is often unnoticed—there are vestiges of Ottawa’s Carnegie Library there. The Rockcliffe Park Pavilion is a good spot too that is not well known.”

Waldron says that he hopes Exploring the Capital provides readers with the scaffolding to understand Ottawa’s architectural culture, but also encourages discussion beyond the book by equipping readers with the knowledge to both appreciate the beauty and dynamism of Canada’s capital city and to think critically about Ottawa’s heritage and future.

“The idea of the book is to be foundational. Essentially, a beginning for others to bring more developed narratives to our identities. For example, there are touchstones to the Indigenous presence, but there could be more. We must think about that.”

The Origins of Exploring the Capital: An Architectural Guide to the Ottawa Gatineau Region

Waldron decided to take on this project after re-reading prominent heritage conservationist, Harold Kalman’s popular 1983 architectural guidebook, Exploring Ottawa. The city has, of course, evolved over the last 35 years, and so Waldron, a Guelph Alumnus and celebrated twenty-year veteran in the field of culture related to heritage and history, called Coffman with a proposal to help create a modernized incarnation of Kalman’s classic architectural guide.

“He thought that the new book should have all new photographs and wondered if I would be interested in doing them,” says Coffman. “This book was very much Andrew’s baby, in that he originated it and is the author. He did the research and hired one of our recent grads, Leanne Gaudet, to help with that.”

Waldron immediately knew that he would ask Coffman to collaborate on the project. “Peter has astoundingly impressive photographic skills. I had seen his work on churches and knew that a new publication would require a very talented photographer to create an attractive book.”

It is safe to say that at the time time, Coffman didn’t quite realize what he was getting himself into. Reality hit when Waldron relayed a list of more than 400 names and addresses of the buildings to be photographed. “The list was … long,” says Coffman, “but there wasn’t much negotiation between us over the content. It was extremely well-chosen, and I didn’t have much to add or subtract.”

Coffman and Waldron met back in the early aughts through the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada when Waldron was vice-president of the Society. As their comradeship evolved, so too did their roles at the Society— Waldron would go on to become its president, a title he would eventually pass to Coffman.

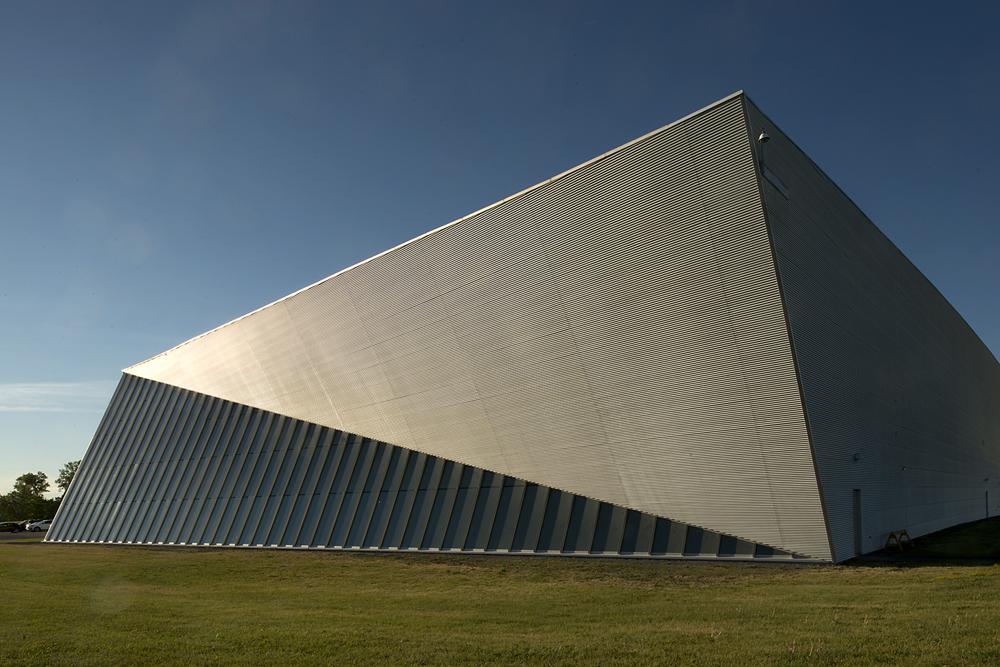

[wide-image image=”23903″ /]

While Waldron has been an Ottawa resident since 1995, Coffman is still relatively new to the city, and due to the demanding nature of his academic role, he hadn’t had the opportunity to explore the city to the degree he’d like. The exhaustive nature of the list, his collaboration on Exploring the Capitaloffered Coffman the opportunity to investigate Ottawa in the detailed way he had intended for years.

“I just rolled up my sleeves and got to work until I had a checkmark beside every building on the list. It took about four years; it is the biggest photographic project I’ve ever taken on.”

“The logistics were tough, and I quickly realized that the meticulous planning required was going to sink me. To prevent this, I brought my wife, Diane Laundy, on board.” Laundy is a professional event planner, so her strengths correspond very neatly with what Coffman describes as his weaknesses. Laundy is also an accomplished photographer who has exhibited her work several times, she knows what Coffman is looking for in terms of lighting conditions and so on.

“Diane went through the spreadsheet and organized it into a series of day or half day outings according to geographical convenience and building orientation relative to sun position. The result was a shooting list that maximized efficiency and likelihood of getting optimal light. It almost sounds like planning a election campaign, but the sheer volume of work, done on top of a very demanding day job, required a very methodical approach.”

On the appointed shooting days, Coffman and Laundy would head out according to Laundy’s itinerary. With all the planning done, Coffman could concentrate on what each building needed for the final image.

“We became a ruthlessly efficient shooting machine, which is what you need to complete a project of this scale,” he says.

“In retrospect, had I been canny enough to work out how much time this would consume, I would probably have turned it down, but luckily I wasn’t and so began my incredible personal journey of doing just what the title says—exploring the capital.”

Coffman’s goal in capturing the city through photography was to treat every building as respectfully as possible and try to come up with something like a portrait of each. “Just as I would if they were people,” he explains. “There are, of course, limits to where you can put a camera and tripod on a busy city street, and often only one side of the building is accessible. But there are still lots of decisions to be made in terms of framing, context, angle of view, and time of day. The word ‘character’ is used a lot in connection with buildings. It’s a bit of an amorphous and highly subjective term; nevertheless, it was my task to arrive at some sense of that character and evoke it in a photo as well as circumstances would allow.”

Investigating Ottawa in such great detail might have been a new experience for Coffman, but architectural photography certainly was not. Long before Coffman ever considered pursuing a career in academia, he was an accomplished professional photographer. He worked in a variety of job within the field, including a position at a company that designed building interiors. This meant much of his photography was architectural in nature. Given the requirements of his job, it is perhaps unsurprising that a pre-existing love for buildings began to manifest itself even more intensely within Coffman.

Soon he found himself taking photographs of buildings in his spare time and eventually he decided to drop commercial photography altogether to indulge his passion. “I went back to school to study architectural history and ultimately became an architectural historian. But I took my photographic training and experience with me into academia, and they have served me extremely well.”

As is palpable in Exploring the Capital, this fervour hasn’t died down one bit. Coffman’s brought this enthusiasm to Carleton University where he has a reputation as one of the most passionate professors in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. His research focuses on the exploration of cultural and political meanings that have been attached to the Gothic style from the twelfth century to the present day and is the former Supervisor of History and Theory of Architecture (HTA). HTA is described as a program that “explores the history, meaning and social significance of the built environment, and how it both reflects and shapes human circumstances.”

He also regularly writes about architectural happenings in the Canadian context via his blog and has a variety of photography exhibitions including, Anglicana Tales, an exhibition of architectural photography at the Dalhousie Art Gallery (2010), and Camino, at ViewPoint Gallery in Halifax (2009). In fact, Coffman is so absorbed by architecture, that even when he takes a break from work, he still prefers to explore. “Whenever I’m not tied to campus I travel and photograph buildings. The ‘vacations’ my wife and I take are, for better or worse, always informed by where there are buildings that I am dying to see and photograph. I use many of these photos for my academic publications and even more of them for my lectures. I still think of myself as a photographer as well as a historian.”

Waldron and Coffman are kindred souls in the sense that they both live and breathe their field of expertise and both tackle their subject matter by implementing an interdisciplinary approach. As is beautifully demonstrated in Exploring the Capital, they also both aspire to affect change towards a renewed or emphasized appreciation for buildings and heritage sites.

Waldron began his career in the field of culture, heritage, and history over twenty years ago. Over this time, he has researched, and managed projects intended to understand. and preserve many National Historic Sites and he is always searching for opportunities to connect Canadians with the wealth of cultural history in their country.

Waldron has done so in long held roles with the Federal Government, including a variety of senior positions at Parks Canada. He now works at Brookfield Global Integrated Solutions, where he has created and implemented a new heritage conservation program for the company. Needless to say, the book’s writer is one of Canada’s pre-eminent voices on architectural heritage and culture.

As mentioned, the two creators of Exploring the Capitalalso share an affiliation with Carleton University, and unsurprisingly, they both cherish Carleton’s physical space and possess strong opinions on how the university fits within the greater Ottawa landscape. Waldron explains that Carleton originated as part of the decentralization push to spread the city further from the core after the Second World War. “This was already happening with government campuses—Confederation Heights, Tunney’s Pasture, NRC Campus, for example,” he says. “Carleton’s planning was actually an impressive applied modern plan in that the concepts may have some precedents in the U.S., but the modern campus between the 19th century engineered canal, and the less tamed river was a perfect frame to build a very rational campus.”

Coffman also treasures the architectural history and cultural worth of the university.

“Carleton has some outstanding modern designs as well as significant heritage value. This seems a paradox to many because a lot of people think that heritage must mean very old. But heritage value derives from a place’s ability to encode and communicate the cultural values of its time, and Carleton—especially the earliest surviving buildings, like Paterson Hall—excels at this.

A building like Paterson Hall exudes confidence and optimism in the idea of modernity, and a crisp, clean sensibility that seems ready to bring a venerable city and its institutions to the cutting edge. The Modernist heritage of Ottawa—or for that matter of Canada—is so often overlooked, and Carleton is a good example of that.”

When asked about Carleton as a heritage site, Waldron, true to form, vehemently defends its heritage.

“Unfortunately, the values of the original Carleton campus are not well appreciated today. This quality goes back to the point that there is a willful ignorance of the past to serve the goals of the future. In a more ethical and responsible world, decisions in the 21st century should be based on the past, present, and future. There are still those who ironically hate the concepts devised 50 years ago, yet apply the very same approaches today!”

This staunch approach is yet another shared disposition of the guide’s writer and photographer, and they hope the importance of citizen vigilance towards our architectural tradition is a message that the book actively transmits. “We have a built heritage of exceptional variety and beauty; one that speaks of the textured and nuanced history of this place and the people who made it. But it’s underappreciated and constantly at risk,” says Coffman.

“As we’ve seen recently, not even the Château Laurier, in the heart of the parliamentary precinct, is safe from mutilation. As a city, we’re under a lot of pressure to develop and intensify, and the people driving that process often don’t care about what they destroy, or the beauty and stories that are lost. Preserving our history and stories will certainly not happen automatically—it’s going to take awareness and effort.”

Coffman and Waldron encourage Canadians to defend this heritage by doing precisely what the book’s title exhorts. “Explore the city, and experience the many wonderful places it has to offer and the rich history they signify,” says Coffman. “Then be ready to go to bat for it.

When someone proposes demolition or disfigurement of a property that you think has value, write to your city councillor, attend meetings and lobby your fellow citizens. Refuse to take the annihilation of our history lying down.” Waldron explains that it might mobilize citizens to consider what is at stake by asking them to reflect on the city’s scope. “I think we need to see the region from imagining it after the last glaciation to now. Imagining the region as a place that has evolved from ten thousand years ago to present day. The region has been a place of meeting and culture for millennia.”

Reading Exploring the Capital: An Architectural Guideto the Ottawa-Gatineau Region is an excellent way to explore, discover, understand, and better appreciate the beautiful City of Ottawa.