Noah’s Blog – An Introduction

By Noah Bendzsa (Fourth Year Student, English)

The Department of English Language and Literature and The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences’ Student Blogger for 2021/2022

I am supposed to introduce myself. I am not Jaclyn Legge and, therefore, am someone else, something different. At first, I toyed very briefly with the idea of emulating Anne Carson: “Noah Bendzsa was born in Canada and does not know ancient Greek.” It’s playful but hardly sufficient. Even Carson has had more written about her than that.

In drafts two through five, I entertained a different idea. I might avoid introducing myself altogether, assume my being, and begin in medias res. I began to write—unsystematically, compulsively—about two subjects that had been on my mind for some time: Evan Rachel Wood’s presence in Green Day’s prefab music video “Wake Me Up When September Ends” and Emily Ruskovich’s takeaways from the “The Love of a Good Woman.” I did not get far writing about either of those things. My last attempt at this kind of writing was to try to interpret a cryptic Don DeLillo quotation from Underworld, which I believed would illuminate my need to write about such disparate subjects. As it turns out, I misremembered the passage; I believed it to be about the duty and impulse to record, but it is actually about satisfying memories of “old times,” especially those shared with erstwhile lovers (DeLillo 64). Far too personal—that was certainly not what I wanted to write about.

I have never been able to comfortably speak or write about myself. Do not think that it is out of any misguided sense of duty to politeness. It is partly because I am a private person, partly because I see writing about the self as a largely futile task. (I will this from an expression of pessimism into one of realism.) In addition to a confused experiment in biochemistry, we are constructions of our stories and the stories others tell about us. The issue is that the only lens we have to view ourselves is warped, and so these stories and our identities are unstable.

I often default to throwing up my own identity on the foundations of the most dramatic stories in my repertoire. I couldn’t stand being an unreflective bore, and I find these stories are the most engaging for listeners. Here are a few. When I was eight, while spelunking, I punctured the skin of the back of my head. It bled profusely, and I thought I was going to die. (I was a romantic and theatrical child.) When I was twelve, I broke my arm in rural northern Ontario. It took ninety minutes to get to the hospital, over poorly paved roads. The relatives I was staying with were as distressed as I have ever seen them, which I am sorry for, as the accident was my fault. My normally tough-love grandfather read aloud to me from Rum Punch, while I was laid up in the E.R., waiting for my radius and ulna to be manipulated back into place. When I was seventeen, I gave the first half of my valedictory speech in character as Groucho Marx. “Let me unzip my sweatsuit,” I said of my gown. My speech advisor, who didn’t know what I was going to do, got up and threw his back out. (He alleges this was unrelated.) My peers, not up on their vaudeville and nineteen-aughts to -forties humour, were baffled.

These stories, the sketches of them I have pencilled, jump through the years of my life because it has been largely unextraordinary—or no more extraordinary than anyone else’s. But, far from complaining, I enjoy the ordinariness of my life. Dramatic stories of high jinks and disaster may be entertaining for casual listeners, but they are ultimately guests who overstay their welcome and leave rings on the coffee table. I most enjoy plain stories concerning small, everyday occurrences and observations. Going to buy groceries; a bus ride to physiotherapy; something heard on the radio or learned on the Web; common, irrational fears of failure and exposure. These personal stories are the most intriguing and multifarious, and best reveal a person’s ostensible character and—dare I write it?—“the nature of the human condition.”

Much of literary and visual art is populated by the small observation or seemingly meaningless incident. The recently reappraised John Williams novel Stoner (one of my favourites) is predominantly a collection of small incidents, the play of light and shadow, in the life of its protagonist, an early-twentieth-century Missourian college professor. A large part of why Alice Munro, whose work is the subject of my undergraduate thesis, is such a tremendous writer is because she is able to so perfectly capture little details, like the feeling of lightness when wearing “rubbers” after a winter of boots (Dance 120). But, despite an early Munro surrogate’s desire to record “every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every smell, pothole, pain, crack, delusion” (Lives 201), I think Mary Pratt, the Nova Scotian photorealist, can at times be an even better observer of the everyday. Of her 1969 painting Baked Apples on Tin Foil, she says, “These apples are almost jewels, set in silver, gold, amber, and yet are obviously mundane, arranged in rows for ‘proper heat distribution,’ on tin foil for ‘easy clean up,’ redolent with cinnamon and cloves. They refuse to be boring—flaunting their romance despite every effort on my part to tear them from their history and their legends. They cry to be celebrated” (qtd. in Gwyn and Moray 42).

The memories that currently “cry to be celebrated” in my own life are those of my cousin Cary and my brother, Zooey. (I have changed their names.) I have been thinking about Cary for fairly obvious reasons. He and I spent some time alone together this summer, when he drove down for the weekend to where we were staying, in Coldwell, Ontario. I don’t drive, so he took me into the nearest town, one day, and we went shopping. Another day, we biked side-by-side to a café, on a wide dirt path that connects the settlements adjoining Coldwell. With most of my worries and anxiety deferred, surrounded by the pacifying bucolic landscape of southern Ontario, I wondered what in life could be better and felt immediately nostalgic for the moment I was in, and wanted to live there. Cary was part of that.

Why I think of Zooey now is a little different from why I think of Cary. Since he was born, this is the first year of my life that I will be without my brother. (He is now a freshman, living in residence, at an east-coast liberal arts college.) Even Cary’s image, built over precious few visits since the mid twenty-teens, has only a few discontinuities—since when has he been old enough to drink?—and gives the illusion of stasis. Zooey is harder to see, since he has been here every day for these past eighteen years. The changes in his character, despite their importance, appear minute and may only be glimpsed peripherally. His abiding image hung over the centre of my eye like a cataract, and now it is gone. His absence has forced my vision to the sharp edges of this newly clear space.

As a child, Zooey was strong, compact, and unflaggingly optimistic. His nickname was Serg, an abbreviation of “sergeant.” He was always the biggest kid in his grade, had a barrelling walk, and wanted to impress his own kind of seriousness on everyone, even adults. None of this has really stopped being true; it has only been let down, like rolled cuffs, as he has grown older.

When he was eleven or so, Zooey began playing a competitive sport—I’ll say tchoukball—to great success. (He is now playing for his college’s varsity team.) He went to tournaments in Hamilton, London, Toronto, and I began to see less of him. The past few years, much of his free time has been spent in the gym or on the track. I’ve been so proud of him for so long that it feels like a hopeless task to try to adequately express my pride. When my friend Beatrice would ask how I was, in high school, I would invariably tell her about how tall my brother had gotten and how he was playing on three different tchoukball teams and how he was scoring n number of points a game. With him, though, I almost felt that I needed to downplay the importance of his accomplishments to me. I would make statements like “the world doesn’t revolve around tchoukball” and reproach him for his monologues—while mine were always far longer and more self-indulgent—about the style of play of his tchoukball heroes. I regret my inarticulateness and my buried sentiments, but it doesn’t and didn’t seem like there was a lot else that was open to me, as an older sibling: this was how we talked.

One of the best things to come out of being stuck at home for so many months was that, with gymnasiums closures, Zooey and I got to spend more time together. Summer afternoons, we would watch our favourite soap operas. We lay on oversized, under-stuffed pillows in my rented room in Coldwell, watching on my computer screen. As we rooted for the American patriarch to show up the officious Europeans, the vagarious blonde to get a grip and make up her mind—the Swede or the Louisianan—Zooey would hoot, grin, and talk at the characters. When he spoke, it was an eruption of the half-abashed sweet talk of television viewership. Where had he learned?

Another time, when my magazine subscription accidentally removed me from their mailing list and stopped sending me new issues, we walked the five-mile round trip to our local bookstore, to try and get the one that they had failed to send. (From that perspective, it was a fruitless endeavour—the bookstore only gets the magazines in a week after they are sent out to subscribers.) I don’t think we talked about anything very important, just how fast we were walking and the distance to the store, something about how he was feeling about going away. It was such a beautiful, warm day. Zooey holds his chin too high, as though he needs be any taller, and still has the vestiges of that barrelling walk he developed as toddler. Despite his sportiness, he never fulfilled the negative stereotype of an athlete, and has always been an incredibly kind, gentle, and self-sacrificing person. He makes me feel safe.

In the end, I have neither introduced myself (I was born in Ottawa, in 2000. I grew up in Riverside Park and wished it were elsewhere) nor begun with a dis-authored torrent of words. Instead I’ve written about two people who are close to my heart, whom I have felt compelled to write about. And for this reason I’m not sure this post has gone anywhere for anyone aside from myself. It’s my hope, though, that anyone who has read this can see some small measure of themselves, their own ordinary stories, in my life—no matter how different our lives might be—and find comfort in that, or else take the time to examine and enjoy their own memories of people whom they love.

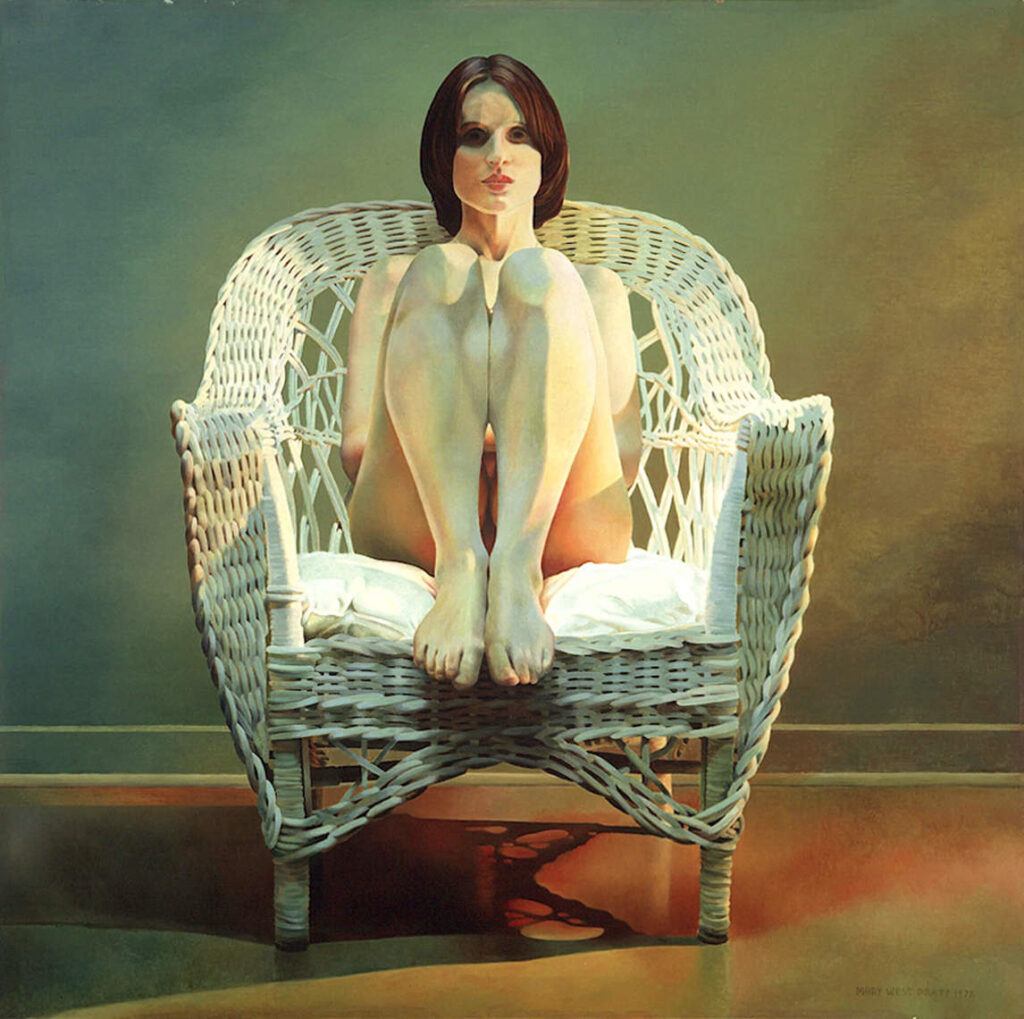

Although Munro is often accused of burying pieces of herself and people she knows in her work, it is again Pratt who grabs the ring, for she assuredly does. I can’t think of a more radical, innocuous, accusatory painting than Girl in a Wicker Chair (1978). It is Mary looking at Donna Meaney looking at Christopher Pratt looking at us, all in a single gaze. And aren’t we meant to see in that simple look the whole of those relationships?

Works Cited

- DeLillo, Don. Underworld. Scribner, 1997.

- Gwyn, Sandra and Gerta Moray. Mary Pratt. McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1989.

- Munro, Alice. Dance of the Happy Shades. 1968. Vintage, 1998.

- —. The Lives of Girls and Women. 1971. Signet, 1974.