The Other NFB

Often hailed as the birthplace of modern Canadian cinema, the National Film Board of Canada since 1939, has offered young creators a platform to act in, direct, film, and explore new ways of entertaining and educating through documentary and drama.

But there’s more to the the NFB than just movies and shorts. There is a less familiar side to the NFB. Last May, an exhibition named “The Other NFB” completed its Eastern Canada tour at Carleton University Art Gallery. “Everyone knows the NFB as a filmmaker,” said curator and art history professor Carol Payne, “but they don’t know these still photographs representing Canada from 1941 to 1984.”

Sandra Dyck, the director of the Carleton Gallery, invited Payne to co-curate a look into the little known still photography division of the NFB in 2012. Covering three decades, they collected 89 photographs from a staggering archive of almost 250,000 pictures that endeavoured to portray life in Canada.

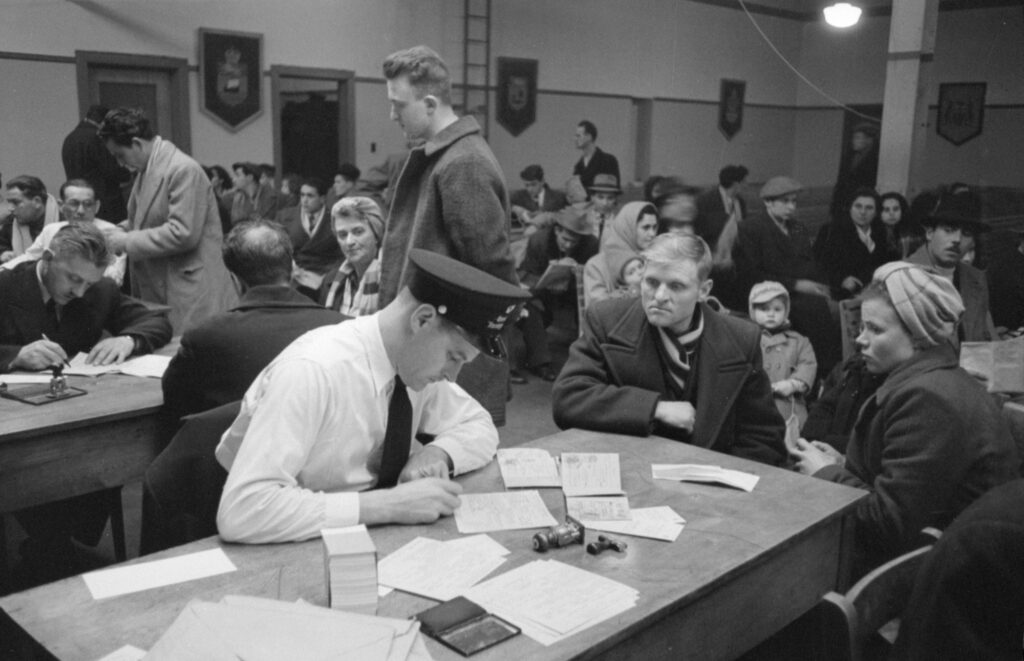

Given that the NFB mandate was to shape a national image both for Canadians and those beyond the nation’s borders, the resulting images were predictably intriguing and idealistic. The 1941 war-time image of Veronica “Ronnie” Foster casually smoking a cigarette on the Bren gun factory line is an example. Another powerful image is the 1953 shot of physiotherapist Mrs. E. Marr encouraging two year old polio patient Dorothy Gifford to learn to walk with braces. These photos were strategically created with the intent to dampen otherwise harrowing societal narratives. “You don’t see Canada in a full sense, you see this glowing image,” said Payne.

Granted, these are but two images out of a quarter of a million which include snapshots of teenagers standing on the sidewalk, Hutterites tending a field, children sticking their heads into maple sap buckets, and Inuit peoples in and around their homes.

Contemporary print from vintage negative. National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque / Library and Archives Canada PA-111579.

In 1941 an order from the Privy Council legislated that the National Film Board become the country’s official pho- tographer. Thus, NFB photos were exclusively used by all major arms of the federal government to promote Canada with no exceptions. “Some governmental departments—including Parks Canada in the 1940s for example—continued to shoot their own images but were legislated to stop,” explains Payne.

The Other NFB was presented at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa in winter and spring 2016 and moved on to the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston that summer and fall. At Carleton, professors from different disciplines brought their curricula into the art gallery to interact with the unique show.

The photography, film, and music of the NFB were examined during the winter 2017 term by Payne working with professors André Loiselle and James Wright. Payne taught the MA course “Issues in the Theory and History of Photography.”

Wright and Loiselle taught the course “NFB Music, NFB Film” which hinged on the prospect of writing music for the film industry. Thus, the stills division and the eminent film portion of the NFB effectively placed the organization on a pedestal for many aspiring composers, photographers and filmmakers.

Two national institutions now house the NFB’s still photography division collection: Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP), where Carol Payne worked as a curator in the late ‘90s and which is now part of the National Gallery of Canada’s Canadian Photography Institute.

“I was curating contemporary exhibitions in the late 1990s, and in the middle of the production rooms there were all these file cabinets,” she said. “They were just sitting there. The archive was eclipsed in the national imagination by the NFB’s celebrated motion pictures units.”

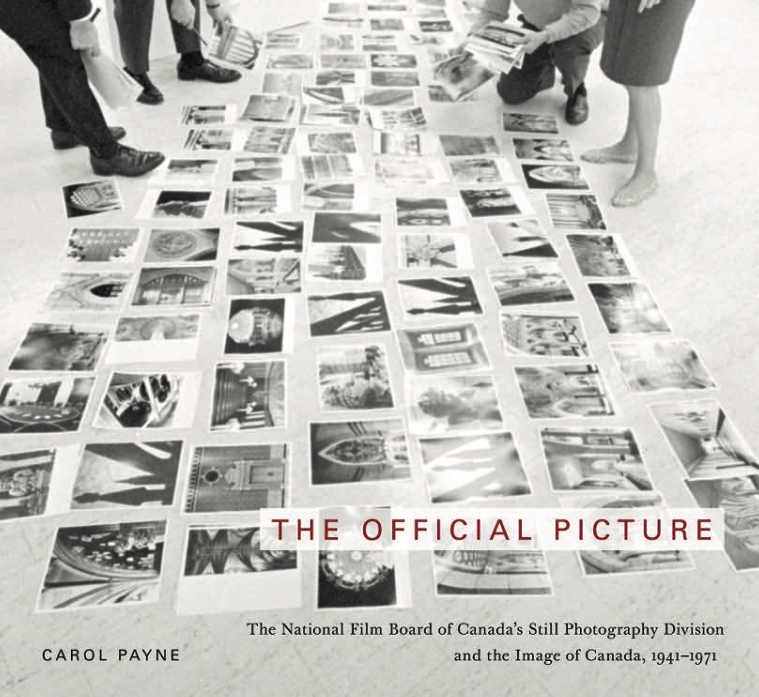

In 2013, Payne published the book The Official Picture: The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941-1971 (McGill-Queen’s University Press) on the “vast but largely forgotten archive of still photographs.” She and Dyck had been talking about an exhibition for a few years. While the book and the exhibition explore the same themes, each is its own project. Both collections are a study of the history of photography in Canada.

“What I argue in the book, and Sandra and I argue in the exhibition, is that these photographs and the archive as a whole are not an objective record of Canadian life in the mid to late twentieth century. It’s a history told from an official governmental point of view, to show Canada in a good light. It’s promotional. Bluntly put: it’s propaganda.”

It’s also maintained that the NFB, as one of the Canada’s most influential cultural agencies, played a key role in nation building and defining Canadian identity through its photographic art. With an exhibition like theirs, Payne and Dyck also demonstrated how archives, no matter their previous intent, can serve as artifacts that inform the present. Many of these photos serve as a reminder of how women’s rights have progressed since the Second World War and how far Canada must go to confront the injustices faced by Indigenous peoples. They also prompt audiences to contemplate Canada’s evolving healthcare system, appreciate our increasingly more diverse population, and consider how the changing face of our physical landscape underscores the dangers of climate change.

In the conclusion of Payne’s 2013 book, she wrote that “the point of the study and of cultural history as a whole, was not to re-enter a past, but to reactivate it.” In doing so, the representation of Canada is re-examined as more than just 2D stills—it’s a deep well of reference that should be dipped into again and again.