Our method of determining seasonal tasks of hunting families from their artifact patterns is explained in this section1. As these families followed the Beverly caribou herd in its annual migrations between the Saskatchewan winter forest and its tundra calving ground west of Baker Lake, we know the month when these tasks occurred because we sectioned and analysed the cementum rings of caribou teeth. Like tree-rings, cementum rings are thin and dark in winter and thick and light in the growing seasons. In addition, similar modern and ancient use of the complete range preclude similar site or hunting camp seasonalities depending upon where the site is situated in the range. In sum, we know herd movements just like past hunters.

Unlike herds, hunting families were unable to move the full length of the range. Rather, southern forest people went to treeline, while northern forest people journeyed far north, some to the calving grounds. The different cultures for the past 8,000 years and their distribution have been mapped2. In their wanderings, herd followers lose, alter or discard tools, and by studying tool distribution in their camps, you can reconstruct their activities. Sites were seasonally used, due to the nature of caribou migrations, so tools and their patterns have seasonal ties. Herd followers not only re-use the same sites due to the nature of a herd migrating along its migration route, but herd followers may use the same spot within a site for an identical activity. Just as you prefer to build your tent and fire in the same place in a favorite campsite each year, hunting families did the same. Repeated annual tool deposition from one task forms a pattern (palimpsest), but when many tasks were on the same spot, palimpsests merge and appear illegible, so we must isolate each task on its own pattern. As a task may involve multiple artifacts (e.g., flakes with cores), we test to see if one supports the other.

Tasks are sequential. You are not going to scrape a hide before you butcher its owner, nor butcher it before it is killed. As men usually provide and women process in most hunting cultures, men’s tasks include killing with stone, bone, antler or copper points, plus tool manufacturing; women’s tasks are butchering with knives (may be shared with men), grease (marrow) extraction, meat-drying and skinworking with scrapers, needles and awls to make tents, clothing and mocassins. As camps were briefly occupied, their inhabitants were geared to producing as much dried meat as possible in the shortest time for transport south. To do so likely required organized labour. A woman butchering and piling meat on a skin may have had helpers slicing it into strips for quick-drying on willows, rocks and hearths. Where trees occurred, the people used meat-drying racks resembling fish-drying racks in the forest. To maximize output these secondary activities may have occurred alongside primary activities, or later on the same spots.

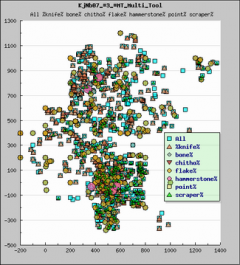

We plot the sequence and use of tools using a functional approach derived from historic records of Chipewyan tool use by Samuel Hearne3 and later fur traders, data from modern Chipewyan informants using traditional methods, and an intuitive grasp of events gained by actually living in Chipewyan camps while excavating them. We also know subsistence options were rare for the Chipewyan because their lives were heavily controlled by caribou – timing of migration, what they could do with meat, fat, skin, sinew, etc. As some areas have artifacts of several superimposed activities, we must separate them. Women may be butchering in one spot while men are knapping stone the next day in the same spot. Scatter graphs are better understood if you project yourself as a member of a hunting family (man or woman)! To understand their culture, you must temporarily discard some Western concepts of order and imposed beliefs.

We plot the sequence and use of tools using a functional approach derived from historic records of Chipewyan tool use by Samuel Hearne3 and later fur traders, data from modern Chipewyan informants using traditional methods, and an intuitive grasp of events gained by actually living in Chipewyan camps while excavating them. We also know subsistence options were rare for the Chipewyan because their lives were heavily controlled by caribou – timing of migration, what they could do with meat, fat, skin, sinew, etc. As some areas have artifacts of several superimposed activities, we must separate them. Women may be butchering in one spot while men are knapping stone the next day in the same spot. Scatter graphs are better understood if you project yourself as a member of a hunting family (man or woman)! To understand their culture, you must temporarily discard some Western concepts of order and imposed beliefs.

|

A Palimpsest reveals repetitive use of numerous tools at this encampment. They are distinct by task and time of activity, and may occupy the same physical space. Measurement grid is in centimetres, and encompasses an area of 16m x 18m. |

The main differences between July-occupied northern tundra water-crossings and August-September-occupied southern treeline sites are size, artifact density and size and specialization. Other differences may be in hunting band content. The northern or KjNb sub-band or hunting unit, while related to the southern KeNi-4 hunting unit, both being in the Thelon Valley, are different people of the same regional band. Similarly for the KkLn-4 and KdLw-1 hunting units in the Dubawnt Valley and over the drainage divide to Black Lake. In our studies, we will mention the Thelon and Dubawnt regional bands and herds. A regional band is never together at one time. Its closest approximation occurs at large treeline sites like KeNi-4 when the more northern KjNb hunters join them in early August and when the southern forest hunting families have not left. All are part of the matrilineal matrilocal Caribou-Eater Dene or Etthen-eldeli tribe that traces descent through the female line and where the new husband leaves his group and lives with his wife’s parents for a period of time. This has adaptive or survival benefits in extending his and her hunting territory. It may also be reflected in camp arrangements and artifact scatters, something we keep in the back of our minds.

Tundra sites are small, artifact-dense and meat-hunting. Treeline sites are huge, uncrowded and hide-hunting, with meat secondary. When caribou pass the tundra sites, their hides have many warble fly holes, but their carcasses have much meat and especially fat after a summer of browsing. By the time they reach the treeline sites, their hides have healed and a sublayer of fine fur formed in preparation for winter. Like tundra sites, meat is valuable for both sexes, but bull meat is unpleasant in October and November rut due to hormones. The thick bull backfat is also gone. With such in mind, you should find proportionally more worn knives and unworn scrapers in northern sites, and more worn scrapers, chithos, hide flexers and skin softeners in southern sites. Hides are the property of women and they have the responsibility of making clothing and erecting tents. Southern sites also have ready access to trees, which facilitate more and larger fires, more tent construction and any projects requiring wood, like tool handles and drying racks. The important proximity of wood completely changes camping. Cooking and construction is easier, and social interaction around a hearth is strengthened. This may be one reason treeline camps are much larger and less dense – people stay longer at one place to prepare for winter and have more room to spread out.

In March-April, subherds in the southern part of the forest begin moving north while subherds in the northern part move out onto the tundra. Hunting families in these areas follow suit, such that the northern band is 100-150 km and a week or two ahead of the southern band – just like the caribou. Of the two north-south parallel migrations of the Beverly caribou herd, the western subherd follows the Thelon Valley, passing the KeNi-4 and KjNb sites, while the eastern subherd follows the Dubawnt Valley, passing the KdLw-1 and KkLn-4 sites. We know they carried tools and raw material from treeline sites into the forest because forest raw material is unavailable. I don’t think they did the reverse because treeline sites were snow-covered in April when the northermost families moved onto the tundra. Note that treeline sites have half the artifact density as tundra sites, yet these sites are much bigger. This may be due to winter preparation of tobaggans, snowshoes and tools for transport into the forest, and for spring prearation of canoes onto the tundra for hunting at the water-crossings. Most types of winter forest tools are smaller than their summer tundra equivalents because hunters had to carefully resharpen their summer tools, removing little material and being very careful not to break them because raw material was distant or unavailable under heavy forest snowcover. Forest raw material was also cruder than tundra quartzite and chert.

Place yourself in the northern band at the headwaters of the Thelon or Dubawnt Rivers at treeline. You are on the snow-covered track of the subherd that left the forest in April for the calving grounds. You intend to intercept it at the KjNb or KkLn-4 tundra water-crossings on its July migration south! As the rest of your band will follow your path but only reach the KdLw-1 and KeNi-4 treeline sites, they leave the forest weeks later. You won’t see them until August.

1 may be read in conjunction with website: Gordon 1976. Man-Environment Relationships in Barrenland Prehistory. The Muskox 1981; Migod – 8,000 years of Barrenland Prehistory. Mercury 56, Archaeological Survey of Canada; and James J.E. Smith 1978. Economic Uncertainty in an “Original Affluent Society”: Caribou and Caribou-Eater Chipewyan Adaptive Strategies. Arctic Anthropology.

2 Gordon 1996. People of Sunlight; People of Starlight: Barrenland Archaeology in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Mercury 154, Canadian Museum of Civilzation.

3 Hearne, Samuel. 1958. A Journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772 (ed. by R. Glover). Reprinted Toronto: Macmillan 1958.

– 1971. A Journey from Prince of Wales’ Fort in Hudson Bay to the Northern Ocean, Edmonton: Hurtig.