From the Director, Shane Hawkins

I AND THOU

I am just you.

I am your past haunting

Your present and your future.

—Refaat Alareer, from ‘I Am You’

For this Love is enraged with me,

Yet kills not; if I must example be

To future rebels, if th’ unborn

Must learn by my being cut up and torn,

Kill, and dissect me, Love; for this

Torture against thine own end is;

Rack’d carcasses make ill anatomies.

—John Donne, from ‘Love’s Exchange’

As we head into the fall term and reconvene for another year of classes, it seems like an opportune moment to reflect on some principles adopted by the Bachelor of Humanities program in 2018. I refer to the so-called Chicago Statement, which is a document drawn up by the Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago in 2014 and which has been adopted by many universities and colleges in North America who cherish the idea of free speech as well as open and unencumbered dialogue. As the document states, the committee’s charge was to draft a statement “articulating the University’s overarching commitment to free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberation among all members of the University’s community.”

In the abrasive and often abusive climate that one may perhaps still haltingly refer to as the marketplace of ideas, some reflection on that commitment seems as timely as ever. I want to point out first of all that in formulating the Statement, the authors recalled the long history of free inquiry at their own university and highlighted its reaction to campus protests in the 1930s:

President Robert M. Hutchins responded that ‘our students . . . should have

freedom to discuss any problem that presents itself’. He insisted that the

‘cure’ for ideas we oppose ‘lies through open discussion rather than through

inhibition’. On a later occasion, Hutchins added that ‘free inquiry is

indispensable to the good life, that universities exist for the sake of such

inquiry, [and] that without it they cease to be universities’.

The Chicago Statement continues: “Because the University is committed to free and open inquiry in all matters, it guarantees all members of the University community the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn.” The wording is here is deliberate. “All members” includes—must include—the university’s students. The idea of a University guarantees them, with certain reasonable restrictions, the latitude to speak, write, and challenge, just as it calls upon faculty members to listen and learn. Those five verbs belong together; speaking and writing are the inseparable partners of listening and challenging, and without these together we put at risk our main objective: learning.

The authors of the document were not naïve: “Of course, the ideas of different members of the University community will often and quite naturally conflict.” Indeed, how could it be any other way? We have not gathered on campus to politely discuss the weather or contend over the proper arrangement of the tulip beds on the far shore of Dow’s Lake. We are here because we care to learn about what matters and what is dear to us. For many the university is still a place to nourish our personal convictions about how and what the world around us could be or ought to be, and therefore the university as an institution presents a long history of conflict that on occasion is violent, bloody, and even deadly. The recognition of inevitable conflict leads to an important stipulation in the Chicago Statement:

But it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals

from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply

offensive. Although the University greatly values civility, and although all

members of the University community share in the responsibility for

maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility and mutual

respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of

ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community.

In a word, the University’s fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation must not be suppressed merely because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even by most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed. It is for the individual members of the University community to make those judgments for themselves and to act on those judgments not by seeking to suppress speech, but by openly and vigorously contesting the ideas they oppose. In fact, fostering the ability of members of the University community to engage in debate and deliberation in an effective and responsible manner is an essential part of the University’s—and the College of the Humanities’—educational mission.

To my mind, certain corollaries follow from these ideas. First, students and faculty must not only feel free to express their own ideas, they must also be free even to err without the fear of retaliation, public shaming, and charges of naïveté or slow-wittedness. Students must be safe to argue for their own opinions and against those of other students and faculty and to do so free from retribution.

Andrew Delbanco, who teaches at Columbia University, wrote an excellent book called College: What it Was, Is, and Should Be. He observes that one of the longstanding foundational ideas of a college is this: “the college classroom has been a rehearsal space for democracy—a place where students learn to speak and listen with civility to peers whose perspective on the world differs from their own.” What strikes me now about his words is the spot-on observation that the classroom is a “rehearsal space”. It is not a stage for the eyes of the world. The discussions and arguments of students within the College should remain safely within the walls of the College, and if there are mistakes and missteps along the way, the faults of youth ought to be gracefully forgotten as opinions change and sensitivities mature, always with the humility that recognizes learning as a life-long project for us all.

Of course, I do not mean to suggest that we should assume students are always mistaken! Students are usually right and even prescient with regard to moral trends, so much so that they can make staid institutions and their doyens seem backwards by comparison. And at other times our disagreements are sharp but best described as differences of opinion rather than in the stark moral terms of ‘truths’ and ‘lies’. In any case, we should pick our fights with the opinions themselves, not with the people in our learning community who espouse them.

As a professor and as the Director of the College I know that my professorial colleagues will teach and publish scholarship and occasionally opinions with which I disagree. I do not find that comfortable, but I must insist on their right to speak as their judgment directs them. I expect them to extend the same courtesy to me. Academic freedom does not imply neutrality on any given topic, and it guarantees that my colleagues will be free to voice all sorts of ideas—even those that I personally find morally irresponsible.

It is not my job or desire as Director to police, confirm, or repudiate views of the faculty. Nor is it the role of the College, which does not and cannot pronounce on issues beyond the realm of its academic duties. Plagiarism, research papers, course design, program content—on issues like these we can pronounce as a body. But we do not pronounce on areas such as public health, federal monetary policy, immigration, and a great many others whose sphere of activity is located outside the classroom and the university walls. Of course, students and faculty—like all members of society—are free to express their opinions on all of these areas, but these topics, however pressing, are beyond the purview of the College as a body, even in the unlikely event that it were possible to reach agreement amongst ourselves on such issues. The College does not pronounce—pro or con—on the published views of individual faculty members, and silence on their opinions is neither an indication of support nor a condemnation.

But allow me to add this: I always understood as a student that what my professors presented to me in my courses was a curated presentation and curious mix of fact and learned opinion, and that I was under no obligation to believe any of it wholesale. On the contrary, what was expected of me as a fledgling scholar was that I would put to the test and make proof of their knowledge for myself. If perhaps students no longer come to university with that understanding, I believe they nevertheless develop it quickly. And so I am not terribly perturbed when students are exposed to ideas I personally find regrettable, because I believe that our students are well trained to discern and make decisions on difficult issues for themselves. And I trust them to do the mental work. To quote Delbanco again, “the most important thing one can acquire in college is a well-functioning bullshit meter. It’s a technology that will never become obsolete.”

Second, with all due respect to the achievements of learning, arguments from authority do not count for much here: there is no reserve of experts on campus to whose opinions we must all defer. Even a few years of grad school and a PhD do not somehow confer upon one the right to do the speaking and writing without also sharing the responsibility of listening and learning. The suggestion that only members from one corner of the University can engage or expound on a given fraught subject of the day runs contrary to the principles to which we ought to aspire. This is especially true regarding those topics about which reasonable and intelligent people disagree and the complexity of which requires more expertise in different areas than any single person, if we are honest with ourselves, can possibly muster.

Nassim Taleb, and probably others before him, observed that the problem with experts is that they do not know what they do not know. It seems to me that they are also often assured that they know that others do not know. Speaking personally, in many things I prefer to follow the example of an avowed non-expert, Socrates, who found that wisdom began in the recognition of his own ignorance. There are a great many things in the world about which we might disagree, and some of them are extremely important issues about which we cannot plead ignorance because they demand decisions of us. We do not have to come to an agreement on these issues, of course, but it is imperative that here, in our little corner, we reserve a space to discuss and debate them and that all of us are welcome to participate in the conversation free from fear.

College News

Annual First Year Trip to Montreal

At the start of the fall term this year, first years students went on a field trip to Montreal, which included a visit to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and tickets to see The AURA Experience at the Notre-Dame Basilica of Montreal. Students had plenty of time to explore the city and get to know each other better.

Humanities Colloquium 2024

The annual Humanities Colloquium provides students in the College of Humanities with an opportunity to present their work to peers and faculty, and hold engaging discussions with their audiences. This year it was held on Saturday March 23rd, 2024 and was another great success. Check our website and social media if you’d like to attend the 2025 Colloquium in March (more details to come in the new year).

Click here to see the Program and Abstracts

Ipso Facto: The Carleton Journal of Interdisciplinary Humanities

Ipso Facto is a student-run undergraduate journal initiated in 2021. Its aim is to publish papers written by undergraduate students on an annual basis. Students are encouraged to submit papers on a wide variety of topics in the interdisciplinary humanities. Papers may either be particular to one field or draw on interdisciplinary approaches to make an argument. The main goal of the journal is to publish articles and letters that take an original stance on a topic or question.

Ipso Facto is a student-run undergraduate journal initiated in 2021. Its aim is to publish papers written by undergraduate students on an annual basis. Students are encouraged to submit papers on a wide variety of topics in the interdisciplinary humanities. Papers may either be particular to one field or draw on interdisciplinary approaches to make an argument. The main goal of the journal is to publish articles and letters that take an original stance on a topic or question.

Electronic Versions of the journal can be found below.

Volume 1 (2022)

Volume 2 (2023)

Volume 3 (2024)

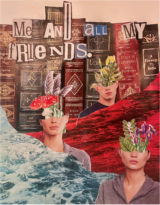

NORTH

Every year Bachelor of Humanities students contribute to NORTH, the students’ literary publication. Founded in 1999, NORTH has been a forum for poetry, short stories, art, and photography. Throughout the year the NORTH team organizes events like poetry nights, air dry clay days, and music nights. To keep up with NORTH and see weekly art features from the Hums community follow us on Instagram @humsnorth.

B.Hum Recruiting Events

Please help us spread the word about the Bachelor of Humanities: to your neighbours, your friends, and even your children and their friends! We have both in person and virtual events to learn more about the program and you can mind more information here.

Alumni News

Are you an alum with some professional or personal news you’d like to share? Keep us updated!

Do you know any prospective students who would be interested in the BHum or would you be interested in helping the College with recruiting events? You can find information here.