- Greetings from the Director, Shane Hawkins

- First Year Trip to Montreal

- New York City Trip

- College News

- Fall 2023 BHUM and BJHUM Graduates

Greetings from the Director, Shane Hawkins

Somehow we find ourselves in November. The term is hurtling along and I am very pleased to share with you some updates from the College. In September we kicked off the year in fine form with a student orientation and a Welcome Event, with nearly sixty new first-years gathered to sign the College Book and join the program.

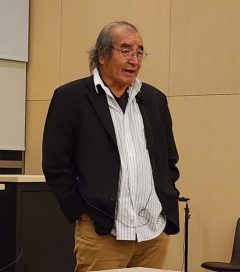

On the twenty-third our first years made the annual trip to Montreal. Then, a few days later, the College welcomed playwright, author, and musician Tomson Highway, who delivered an unforgettable monologue on life, language, love, music, and laughter. He spoke in part about his extraordinary and highly recommended memoire, Permanent Astonishment, which recounts his birth in a snowbank on an island in the sub-Arctic, growing up as the eleventh of twelve children in a nomadic, caribou-hunting Cree family, and his experience in the residential school system.

Over Fall Reading Week in October 18 HUMS students, accompanied by our dauntless Professors White and Stephenson, set out on the fourth almost-annual (and first post-COVID) trip to New York City and had a smashing time visiting important cultural institutions.

Finally, we are all very pleased to congratulate those students who graduated this summer and had their convocation this November. Well done to Johann Mecklenburg and Rachelle Savard (University Medal Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences).

First Year Trip to Montreal

Noel Salmond

Thirty first-year students and two from third year accompanied Professors Micheline White and me on September 23. We left campus in the early morning sunshine headed for Quebec. As we crossed the long bridge to the island of Montreal, I couldn’t resist pointing out Lake of Two Mountains on our left as a mythological resting place in the traditional Anishinaabe account of their migration from the East (a mythic narrative we had just read in HUMS 1000). Arriving downtown, the Fall weather in Montreal was benign and balmy and the downtown as lively as ever – including a massive public sector workers demonstration headed up Avenue du Parc to Mount Royal!

First stop: the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Here we divided into two groups; the first went to the Medieval and Renaissance galleries and had the privilege of being guided by Montreal scholar Prof. Laurence Nixon who has studied this collection for decades. Dr. Nixon explained the iconography of a variety of medieval paintings and altar pieces — works that draw on narratives from the Bible but also on non-canonical sources such as the Golden Legend.

The second group went with me to look at contemporary art starting with video artist Lynn Hesham Leeson’s “Logic Paralyzes the Heart”, a thirteen-minute long meditation on technology, ecological collapse, and the surveillance state. We then looked at a sculptural installation by German conceptual and performance artist Joseph Beuys, and ended in the small space dedicated to modern Indigenous art focusing on an early work on birchbark, man changing into thunderbird, by Norval Morrisseau. Both groups also had some time to explore the extensive museum on their own.

After lunch in a variety of venues downtown we re-assembled at 2:00 at La Maison Symphonique at Place Des Arts for a concert featuring the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. Maestro Rafael Payare impressed us with his impassioned and athletic conducting of Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 in D major, “Titan”. We also heard the young Russian virtuoso pianist Alexander Malofeev with an amazing performance of Prokofiev’s Concerto no. 3 in C major. Then, more free time to wander and dine until we re-boarded our bus around 8:00 p.m. for our return to the Capital. Even a long day in Montreal is too short; but it provides a fine entrée to our neighboring city and a really good way for new students to get to know each other outside the classroom or seminar and to experience a taste of the art and music that figure so centrally in the B. HUM program.

New York City Trip

Professor Micheline White

The College is pleased to share the news that we were able to resume the annual cultural trip to New York City this fall. At 4:45 am (!) on a Saturday morning in October, a group of eighteen students, Prof. Erik Stephenson, and I all piled into a bus at Dunton tower and headed off to the Big Apple. We did not let the pesky landslide that left us stranded in Albany dampen our spirits, and we arrived at our hotel near Times Square in time for a late celebratory dinner.

The College is pleased to share the news that we were able to resume the annual cultural trip to New York City this fall. At 4:45 am (!) on a Saturday morning in October, a group of eighteen students, Prof. Erik Stephenson, and I all piled into a bus at Dunton tower and headed off to the Big Apple. We did not let the pesky landslide that left us stranded in Albany dampen our spirits, and we arrived at our hotel near Times Square in time for a late celebratory dinner.

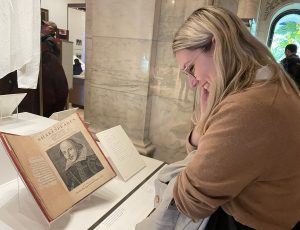

The first day was “library day” as we enjoyed a tour of the Morgan Library and Museum, learning about the transformation of Pierpont Morgan’s private book collection into a public institution in 1924 and the curatorial work of Belle da Costa Greene. We saw three Gutenberg Bibles, manuscripts by W. Mozart, and a book made of purple parchment owned by Henry VIII. In the afternoon, we visited the “treasures” of the New York Public Library and marvelled at a copy of Shakespeare’s first folio, a lock of Mary Shelley’s hair, a piece of Percy Shelley’s skull, a first edition of Phyllis Wheatley’s poems, and the stuffed animals that inspired Winnie-the-pooh.

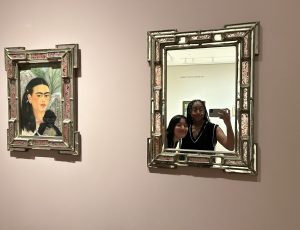

On the second day we gathered at the MET, and what a treat it was. We all headed off in different directions enjoying everything from Egyptian mummies, to Roman statuary, to Japanese woodblocks, to a Manet/Degas exhibit. Most of us staggered out after four hours and headed to sunny Central Park to clear our heads.

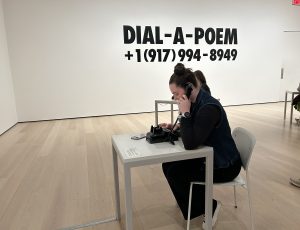

Our final expedition was to the MoMA where we interacted with pieces like John Giorno’s “Dial-A-Poem” and learned about Archibald Motley’s Tongues (Holy Rollers), the first piece by an African American to enter the MoMA’s collection. In the evenings students planned their own activities, seeing shows on Broadway, rollerblading across the Brooklyn Bridge, and enjoying foods from around the world.

We all saw things that sparked our curiosity, made us do a double take, or took our breath away. Let’s do it again next year!

College News

Photo: Nick Peate

News from the Archives by Professor Micheline White

I’m excited to share some news with you about my article “Katherine Parr’s Giftbooks, Henry VIII’s Marginalia, and the Display of Royal Power and Piety,” published in April in Renaissance Quarterly. My findings were picked by a dozen news outlets including the Times (London), The Globe and Mail (gift link), CNN, and CTV News

Those of you who have taken the “Tudor Queens” seminar (HUMS 4902) may recall Katherine Parr’s Psalms or Prayers, a prayer book best described as a piece of military propaganda designed to forward Henry’s military success against France and Scotland. In fact, several of you have given great seminar presentations on this text over the years! Parr’s book was a best-seller, but in addition to arranging for her book to be distributed through a bookseller, Parr and Henry ordered deluxe copies to be distributed as gifts at court. I found five copies of these gorgeous books: they are printed on vellum and are hand-illuminated with gold, blue, red, and green paint.

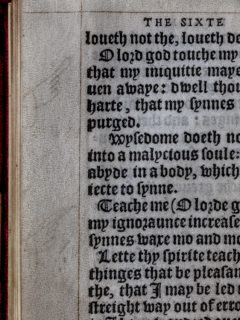

In one of these gift copies – one housed in the Wormsley Library – I discovered fourteen previously unknown handmade annotations. These markings include “manicules” (a hand with a pointed index finger) and “trefoils” (three dots and a squiggle/line). After carefully considering the shape and size of the markings, I concluded that they were made by none other than Henry VIII.

So why might this discovery be noteworthy?

What interests me most is that Henry made these marks in a gift book that Parr (his consort) produced for him. As such, the Wormsley copy sheds new light on their unique political partnership and on the degree to which Henry valued and used Parr’s intellectual and literary skills to forward the agenda of the Crown. The book reveals that Parr was at the centre (rather than at the margins) of political power in the build-up to the war, and it helps us better understand why Henry appointed her to serve as Regent when he left for France.

The annotations also tell us something about Henry’s state of mind in the last years of his life. They reveal that he was worried about his ignorance, waywardness, and sinfulness, and that he believed that God was punishing him by making him “feeble and faint” (he had a debilitating, suppurating ulcer on his leg). Although we usually think of Henry as ruthless, confident, and arrogant (which he was), these markings show that he also experienced bouts of anxiety about the state of his soul and his position as God’s anointed ruler. Henry was never completely alone, and so while I view these markings as personal, I also believe that they had a performative function, and that Henry was displaying to those in his immediate orbit that he was confronting his failings in an exemplary way – by repenting and asking God for forgiveness and wisdom.

Henry VIII’s manicule and trefoil. © The Trustees of The Wormsley Fund and reproduced with permission from The Wormsley Estate. Photo: Andrew Smart.

If you want to learn more, you can check out this episode of the “Not Just the Tudors” podcast.

I also want to send a big “THANK YOU” to all the students who have made teaching Tudor Queens such a pleasure. You inspire me more than you know.

The Interpretation of the Great Books

HUMS 4903A Winter 2024 Hermeneutics

Professor Noel Salmond

I have been teaching in the Bachelor of Humanities program since 1996. We style ourselves a “Great Books” program but I confess I have long felt that it is a major lacuna that we have no course dedicated to the matter of the interpretation of the great books — or of texts or works of literature or art in general. Thankfully, that gets a brief correction next semester with HUMS 4903A, where we will examine case studies in interpretation from a variety of periods and cultures. It’s a seminar on hermeneutics — the academic term for the whole arena of interpretation and a word derived from the ancient Greek hermeneuein, to translate, transmit, explain. We can see within this word, the deity Hermes, messenger of the gods. So the problem of interpretation is to discern the message of the text. What message, or messages, does it seek to convey? What does it mean? And we need to ask, “mean for who?” What did it mean for those who originally composed it; what has it meant over the centuries or even millennia of its transmission; and finally, what might or could it mean for us (or for me personally) today?

I talk about these three short words: did, has, and could, with our first-year students. Reading any text we need to start with asking what did it mean in the mind of the original author or authors. For specialist scholars this requires philological and linguistic skills: knowledge of the original language and its usage. It also requires historical skills: knowledge of the social and political and economic environment that the text arose in. This concern with “what did the text mean” is connected with authorial intent and the question whether or not the definitive meaning of a text lies in the intention of its composer, and, of course, the question of whether or not it is possible definitively to ascertain that original intention.

What has the text meant is concerned with the history of interpretation or what is sometimes called reception history. We need to be interested not only in what a text might have originally meant, but also in how it has been interpreted by an ongoing succession of commentators and communities through time. This, like the concern with did, requires linguistic and historical skills but the interest lies less with some putative original intended meaning and more with how communities have understood and utilized and re-interpreted the text across time.

Lastly, could mean asks what the text might mean for you or for me today. As such it is not confined to historical and linguistic insight and analysis but transcends the confines of scholarly study and engages us personally and existentially. Is this beyond the scope of the academy? Well, we often make the claim that great books are great partly because they are not just of antiquarian interest but have the capacity to address perennial human concerns that affect all of us and at all times.

If the term hermeneutics stems from the Greek, many tend to think of its main development in the domain of Jewish and Christian religion and the question of understanding the Bible. In these religions the tradition arose of delineating “four senses” of the scripture. These were: the literal; the allegorical; the moral; the anagogical (or mystical) meaning of the biblical verse, passage, or longer text. The first sense or level, “the literal” did not mean literal in the sense of actual, factual, or historical but simply the plain meaning or face value reading of the text. So this “literal”, sense was regarded simply as the starting basis or foundation of the other three. To my mind the best illustration of the sheer extent of complicated and inventive interpretation beyond the literal level is found in traditional commentary on that most brief of biblical books, the Song of Songs. This short work of only eight poetic chapters has generated a flood of commentarial ink over almost two millennia. Its plain sense is erotic love but this was rendered into complex allegorical and mystical meanings.

It is within biblical hermeneutics that we also encounter the terms exegesis and eisegesis. The first refers literally to “leading the meaning out of” the biblical passage or verse. An exegete finds the meaning of the biblical passage and conveys it to the reader — or preaches it from the pulpit. But what if the interpretation is fanciful or erroneous and instead of leading the original meaning out, the preacher or commentator is in fact projecting his or her own meaning onto the material? This constitutes eisegesis: reading into the text.

The arising of modern hermeneutics in the early nineteenth century as the disciplined reflection on interpretation is indebted to Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) who, as noted by Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911), saw the domain of hermeneutics as lying between the poles of its being impossible as an enterprise if the world of the text is totally foreign to us, and its being unnecessary as an enterprise if no interpretation was called for as the text was already transparently accessible. Through distance in time, culture, and language we are separated from the meaning of the text but through our common humanity with the author we have the possibility of overcoming that distance. But how is a text to be opened up to us when we cannot question its author in a mutual dialogue? Schleiermacher called for a two-stage process which combined grammatical understanding by the rigorous application of philological skills with the claim that it is possible intuitively to understand the creative genius of the author. By empathically entering the consciousness of the author and, from our vantage point, seeing that author in the context of the Zeitgeist of his time, Schleiermacher claimed we could know the intention of that author better than he knew himself.

A further fundamental concern of nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship was the attempt to establish a basis for the social or human sciences that would make their activities comparable with the achievements of the natural sciences. Dilthey sought such a foundation and proposed a fundamental distinction between the two areas. Natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) are concerned with explanation (Erklärung) while the cultural sciences were concerned with understanding (Verstehen). Natural science deals with things while the human sciences deal with the mental products of the human world. In the latter domain the investigator or interpreter has an “in” as a human being in a way that he or she does not for non-human natural objects or phenomena. He can empathically “enter” the production of another human being in a way that he cannot for a plant, a planet, or a stone. Dilthey sought a firm epistemological basis for the discipline of history and other “human sciences” (Geisteswissenschaften) or the Humanities.

A fundamental problem for these sciences is that unlike the natural sciences they do not use the instrumentation and quantitative methods which provide the purported objectivity of the “hard” sciences. But is the solution to the problem of subjective and arbitrary interpretation a method which claims the ability for the interpreter of eliminating his or her own biases, perspectives, and pre-understandings in an approach to a text as a sort of ahistorical, utterly objective disembodied observer? Hermeneutical theorists such as Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) insist that this solution is not possible for two reasons: 1) Such an attempt at objectivity denies our being-in-the-world, our rootedness in an historical perspective and also denies the very condition for understanding which is our pre-understandings (Vorurteil): a term which Gadamer seeks to rehabilitate from its pejorative connotations when translated as prejudices. 2) Even in the natural sciences the subjectivity (and imagination) of the researcher enters into the interpretation of data and into the initial posing of questions which the collecting of data is meant to test. The retaining of pre-understanding in the philosophical hermeneutics of Gadamer follows from the Romantic hermeneutics of Schleiermacher; it emphasizes ‘belonging’ over the distanciation imputed to Science and Enlightenment. For Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) this stance produces the question of how we can acknowledge our belonging (which seeks to repudiate alienating distance) and at the same time remain critical. Gadamer, following Heidegger, saw the implications of the questions concerning the understanding and interpretation of texts (“regional” hermeneutics such as interpreting biblical materials) as driving toward a “universal” hermeneutics, a philosophical hermeneutics which sees the question of understanding not simply as one dimension among many of human existence but as fundamental to human existence in the world.

Beyond philosophy, the twentieth century also saw powerful currents of literary theory such as New Criticism which denied the necessity of discerning authorial intent. The structuralist approach stressed the unveiling and analysis of the interior dynamics of a text or myth or poem in terms of its fundamental configuration or structure. Post-structuralists such as Derrida posit the autonomy of the text and question the whole notion of the text as necessarily referring to an extra-linguistic reality or world outside itself, or outside the community of texts which constitutes literature.

By now, some of my readers here may feel that engaging in the meta-activity of theorizing about interpretation sounds very dry, dull, and scholastic. But allow me to close by giving one illustration of how this is far from the case. I invoke one powerful and poignant example of how crucial the matter of interpretation can be: the assassination of Mohandas Gandhi. It is well known that the Indian text Bhagavad Gita was the daily guide of the Mahatma and a work that, on a literal level, is about a prince being convinced to go to war; Gandhi, however, interpreted the Gita allegorically as a text promoting nonviolence. In contrast, Gandhi’s assassin Nathuram Godse claimed at his trial in 1948 for murdering Gandhi that his inspiration and justification came from the very same Bhagavad Gita. So here, ironically, we have two individuals from the same religious tradition reading the same religious text but with such a different interpretation that the one shoots the other dead. Textual interpretation is not trivial.

Interpretation is not confined to religion, philosophy, or literature. It figures prominently, for instance, in law: for example, how should a supreme court interpret a nation’s constitution? Should it do so (to borrow biblical vocabulary) according to the letter or according to the spirit? If the constitution was eternally transparent, there would be no need for a court to rule on its bearing on the affairs of today.

Interpretation in a wide sense is the bearing of meaning from one language to another or from one historical epoch to another or from one culture to another which requires both linguistic skill and creativity and imagination on the part of the interpreter. This creative connotation of the act of translation relates it to the sense of interpretation as performance. We say that the violinist “interprets” the musical score, this requires both great skill and training but also creative imagination. Interpretation is both science and art.

Fall 2023 BHUM and BJHUM Graduates

Finally, we are all very pleased to congratulate those students who graduated this fall and had their convocation this November.

We are so proud of what you have accomplished during these last few challenging years and we are excited for you as you embark on the next phase of your life. We wish you all the best in these new adventures and encourage you to stay in touch. As a Humanities and Carleton alumni, your experiences and mentorship are invaluable for the students who follow in your footsteps.

We hope this is a way to keep you informed about the College and for you to stay in touch with us.

Shane Hawkins

Director of the College