by Kate Higginson, CFICE Communications Research Assistant

Often, when we think about the actors involved in community-campus engagement (CCE), we think of our local community-based organizations. However, staying local isn’t the only option for meaningful CCE work. You can also participate in important CCE on an international level. International CCE might involve travelling to a distant community, or working remotely as a part of an international team.

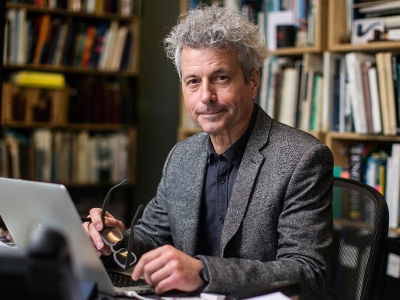

To shed some light on international CCE, its challenges and rewards, CFICE sat down with Dr. Stephen Fai, Director of the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) at Carleton University and Principal Investigator of the internationally-operated New Paradigm/New Tools for Architectural Heritage (NPNT) Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) partnership project. As a partnership project, NPNT focuses on training highly qualified personnel through CCE experiences. It does this by coordinating student exchanges in which Masters and PhD students are placed in internships with international partners. Students work with universities, research institutes, private companies, governments, and non-profit organizations to complete interdisciplinary research and projects exploring the impacts of digital technologies on architectural rehabilitation and conservation.

Funding: International CCE requires more money for travel

An important part of ensuring that your international CCE project is sustainable is securing funding. Proper funding can open doors to up-to-date technologies, account for travel costs, offer compensation to community and researchers, allow for the purchase of general supplies, and much more. For international CCE in particular, having adequate funding to support collaboration, both in the form of travel and technologies to enhance collaboration, is important and generally costs more than it does for locally-based CCE projects.

Based on his experience as an academic planning CCE projects, Dr. Fai recommends applying for relevant grants from funding agencies like the Tri-Agency. These three organizations–the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and SSHRC–are extremely useful resources for academics. With the right grant application to one of these agencies, you could have the necessary funds to get your international CCE project off the ground.

The NPNT project was a good fit for funding from SSHRC, which has a mandate to specifically support student research, learning, and training, because the NPNT project prioritizes student CCE placements as its method for conducting research and mobilizing knowledge. By developing the project around international CCE placements, Dr. Fai and his co-applicants were able to justify the higher travel lines included in their initial grant application. They also clearly outlined the in-kind contributions provided by their international community and academic partners as a means of showing the important commitment of partners to the international placement structure.

That said, funding can come from other sources than just grants. For example, in-kind contributions from partners or sponsorships from external organizations are two great sources of resources for your project. Community organizations might also have the ability to apply for community-oriented funds meant to support new pilot programs or projects. When it comes to funding, collaboratively brainstorming resource outlets is a good way to ensure no stone will be left unturned.

Language, Time, and Cultural Differences: Additional challenges to international CCE

Once the project has been funded, there are a few other hurdles you may need to tackle, such as language barriers, time differences, and cultural differences.

Before embarking on an international CCE partnership, make sure that you have a way of effectively communicating with your partners. This can take the form of language lessons, reliance on translation technologies, or the hiring of an interpreter. Dr. Fai mentioned that within his line of work, language barriers have not been much of a problem. He notes that the digital platforms within which they work often function in English. As long as their partner knows the program, they can simply communicate through the software.

Working on projects involving partners in different time zones can also offer more of a challenge. Finding times for project meetings and check-ins can prove difficult, for example. But different time zones can also be beneficial. For example, if one partner’s day time is another partner’s nighttime, work on the project can literally happen “around the clock”, potentially leading to quicker completion timelines.

Cultural expectations can also be a challenge in international CCE work. For example, in the first year of its project placements, the NPNT project found out that their French and Italian partners had different expectations with respect to placement timelines. As Dr. Fai pointed out: “For us, sending someone away for 16 weeks in the summer makes perfect sense, but France and Italy don’t really work in August.” In order to manage this challenge, Dr. Fai told CFICE that NPNT would accommodate by shortening summer internships, or having students finish their work in a secondary placement.

In addition to these bigger challenges, smaller challenges unique to international CCE can also arise. For example, international travel requires valid passports and visas. There is nothing worse than establishing a partnership with a community across the globe, and then not being able to make it to their project meeting or event. This wastes not only your time, but the time of your valuable partners. Staying aware of both the big and the small challenges in international CCE is important!

Being community-first in a different community

Speaking of important relationships among partners, when engaging in international CCE, or CCE of any kind, CFICE encourages academics to maintain a community-first mindset. In the CFICE context, this means engaging in equitable partnerships to co-create knowledge for addressing pressing community issues. However, the definition of what it means to be community-first can be different for different partners, and can change from culture to culture. As the outsider, it is important to understand your international partners’ definition(s) of “community-first”. In order to do this, you can ask your partners what they hope to gain from the relationship, and together, you can collaboratively develop expectations around how all partners will act in a community first manner.

For the NPNT project, Dr. Fai and his partners have agreed that being community first means having the community reach out to him instead of him approaching the community. To ensure community partners feel comfortable approaching the NPNT project, project members establish open lines of communication, such as sharing project news and calls for placements, that give community the knowledge and opportunity to reach out when they require or desire assistance. For example, after seeing the work the CIMS lab did to rehabilitate the Canadian parliament buildings, international partners in Dublin reached out to Dr. Fai’s team because they were looking to do the same thing. Dr. Fai added that NPNT’s work is inherently community first because they are working on projects identified by community. He notes “the projects we’re involved in are community-based. So it’s not as if we’re doing research and then trying to figure out a way to apply it to a situation.”

Communication is key

As with any CCE work, it is essential to keep the lines of communication open between all partners. This can be difficult even in the most local of settings, so international CCE can require extra effort. Start communicating with all partners right off the bat, and be sure to maintain regular communication with partners throughout the project. Connecting with partners can take the form of weekly email updates, monthly phone calls, or annual meetings. For NPNT, annual meetings at which all partners are present (either in-person, or via Skype) allows the team to stay updated on project progress and encourages openness between partners, which strengthens their relationships. Partners also prepare and share lists of the projects for which they are looking for interns, as well as lists of their own available interns ready to be sent to a project. These lists are shared with all international partners, helping to connect interns with placements, and foster deeper relationships through partners helping each other. According to Fai, these methods of communication ensure, “everybody knows what everybody’s doing, whether they’re directly involved with that project or not.”

Are you ready?

Dr. Fai left us with some final notes about engaging in international CCE. He reminds us, that like everything worth doing, “you have to be willing to take a risk.” It can be incredibly challenging to begin new partnerships, to embark on international travel, and to get to know a different community. However, it can also be extremely rewarding. In terms of an exchange, he notes that “when someone goes to another institution, they take a lot of our corporate knowledge with them. And to have that come back, makes both groups stronger.”

Now that you’re aware of some of the unique challenges that you may face when engaging in international CCE, are you ready?