Skulls for Sale

Prof. Shawn Graham’s research profile will change your vision of what is to be an archeologist.

Originally trained in the traditional study of Roman archaeology, Graham’s scholarly career has evolved to focus on the sophisticated fields of digital archaeology, digital history, and the digital humanities.

The Department of History’s Graham is an active public voice on Twitter and a variety of open access channels like www.electricarchaeology.ca, where he shares, among other things, his research, experiments, ruminations on the modern academy, progressive teaching, and his thoughts and experiences using new learning technology. Woven through his writings are cleverly placed odes to popular art and culture which serve as useful tools to ground and situate the often complex and avant-garde ideas he presents. Notably, Graham is also the founder and editor of the innovative online space Epoiesen: A Journal for Creative Engagement in History and Archaeology. In 2015, he co-story_intro_authored the book Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope which interrogates, describes, and decodes the organic intersection of the digital humanities and big data.

As you can likely appreciate, there exists no utilitarian way to fully capture Graham’s award-winning teaching, research, and knowledge production in a single article. However, his current Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight funded project in collaboration with Dr. Damien Huffer of Stockholm University quite neatly articulates Graham’s broad-stroke academic sensibilities.

Graham’s newest venture demonstrates not only how historians can use progressive tools and platforms to better understand the past, but also serves as an example that you can find just about anything on the Internet. Perhaps most importantly, this research concurrently confronts the brutal history of colonialism and its horrible consequences. While this project is hauntingly compelling, readers should be forewarned, it is also macabre and often tragic.

The busy Prof. Graham was generous enough to sit down with The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences to discuss his career, digital archaeology, and his ground-breaking SSHRC funded project, The Bone Trade: Studying the Online Trade in Human Remains with Machine Learning and Neural Networks.

On one hand, you are an expert analyst of the transpired — artifacts, ecofacts, and biofacts which provide us with context to better understand the present. On the other hand, you are doing this work which implements sophisticated code, relies on social media, and interprets our digitally informed modern realities to better prepare for the future. The Bone Trade melds these two worlds. What draws you to both the “historical” and “innovative?”

Let’s hope it comes together as well as all that! The computational side of this project emerges out of my participation a few years ago in a symposium organized by Kevin Kee (Dean of Arts at the University of Ottawa) on computer vision in history.

I was the curmudgeon at that party — my piece in the volume, coming out later this year I hope, starts with, “We can’t see the past…” Neural network approaches to computer vision were only starting to come on stream at that point, and, at least initially, I found neural network approaches that dealt with text easier to get working on my machine. Easier to get my head around.

Photo: Imaginary skulls: A generative adversarial neural network attempts to create images of what a convolutional neural network sees in images from the bone trade.

Am I correct to understand a neural network as an application tool which sorts through content and then, through the code architecture within it, is able to make its own independent assessments and classifications? For example, if I’m doing research on the various species of mammals, which are most likely cats, which are dogs, which are meerkats etc.?

Right. It is much like passing a whole bunch of filters across an image, each filter allowing a different kind of information to slip through. There are layers and layers of these filters, each one passing up a different vision of what it has seen. The lowest-level filters respond to things like curves or blocks of colour; the higher-level filters respond to more complex shapes — noses, shaggy fur, what-have-you. But how do the higher-level filters recognize these things? It’s in the patterning of links between layers. The output of the network is a percentage guess — 67 percent shaggy dog, 13 percent camel — and since we know what the image actually was in the first place, the network readjusts its weightings between filter layers and tries again.

Eventually, it comes up with a particular pattern of linkages and weights between layers that always identifies the pictures we train it on. When we expose it to a new picture, the pattern of pixels falls through all those filters and weights and if it is a picture of a dog, then that is the pattern of linkages that lights up most – 98 percent shaggy dog. If not, maybe it’ll be a different pattern that lights up. It depends on how the model — the pattern of linkages, layers, filters — was trained, and what it was trained on.

Tensorflow is a tool I use a lot. It is a software library that Google developed to work with these kinds of models; Inception is a trained model on over 1,000 different classes of things using millions of images. What it was not trained on, was human remains. It’s best guess for human skulls is always something like 85 percent jellyfish. But, there’s something called “transfer learning” — we can throw out the last layer of labels on the Inception model, the layer that assigns the labels and give it a new set of training images. Most of the model’s learning-to-see just needs to know what it’s looking at; with only a few thousand images, we can train it to see — to label — new things, to transfer its training to new domains. The second-last layer is a numeric representation of the image it’s looking at — this information can be used to find out what things it thinks are similar, which allows us to look for patterns in how images are composed.

…it comes up with a particular pattern of linkages and weights between layers that always identifies the pictures we train it on. When we expose it to a new picture, the pattern of pixels falls through all those filters and weights and if it is a picture of a dog, then that is the pattern of linkages that lights up most: 98 percent shaggy dog.

Fascinating. How did you come to learn and use these neural networks?

I like to say my job is to futz around with stuff I find on the Internet. I played with these network models I found, I’d train them on ancient Greek plays and have the neural net “write” a new ancient Greek play. As more and more people played with neural networks, they would share their code and their hints and tips. I read voraciously, trying to keep abreast of what’s going on. Last year, Douglas Duhaime, a librarian at Yale, published a blog post showing how he and his team were able to use neural networks – not for labelling images, but for clustering images that the machine identifies as “similar” — the machine sees in 2048 dimensions, by the way — and I realized that I could use this on the Instagram posts that I’d already been collecting. In that earlier project, we were looking at the language of the posts, but now I had the tools to look at the images themselves, and to explore how or if their contents jived or not with the language of the posts.

Which brings us to the content for which you are using these tools — your study of the illicit trade in ethnographical and archaeological human remains through Internet channels like Facebook, Instagram, and eBay. Can you tell us more about this? How common is this market and what exactly does it entail?

Purchasing and selling the physical remains of the dead is a branch of a much larger worldwide phenomenon called “the red market”, or the buying and selling of human tissue, more often than not through illegal or dubious means. This market, which is inherently and profoundly exploitative, includes the sale of everything from human blood, organs, and tissues to the trafficking of living human beings. There has been a significant amount of thought and inspection put towards understanding these illicit channels of commerce used to buy and sell antiquities – statues, pots, mosaics and so on – but a lot less is grasped about the shadowy trade of the dead that exists within today’s red market.

This part of the research is obviously very disquieting — how people market and desire to consume the dead.

We’ve found there’s a market for essentially any kind of remain you can think of. The skeletons of soldiers from the world wars, trophy skulls, instruments fashioned from human bone.

Buying and selling human remains exists in a bit of a grey zone. There’s not a lot of legal cohesion from country to country, which results in operable legal loopholes for vendors and buyers. Overall, it’s easy to find. Like anything else: if someone is willing to buy something, there will be a market for it online. It’s just a matter of whether or not the platform has a meaningful moderation policy. In a wide variety of cases, the answer is, no they do not, and sellers are resourceful in finding ways to sell their products, often hiding in plain sight. Sometimes we track them on social media by hashtags, for example; #vultureculture, #oddities. We’ve set up well over 100,000 scrapes.

Interesting. Do you believe there is a typical profile of the buyers and sellers in the illicit trade of human remains online?

That’s one of the things I want to understand. What attracts people to this? There are so many ethical implications. In our experience so far, we’ve often found that it’s the story that sells the skeleton. Buyers want a rich history for their pieces. They want social souvenirs.

You work closely with Prof. Huffer from Stockholm University on this research…

I met Damien in the coffee line at the conference venue hotel at the Society for American Archaeology annual meeting a few years back.

I’d seen him give a paper on trying to understand the extent of antiquities trading on eBay. He described their methodology, of paging manually through results, following links, writing things down, taking screenshots. Making small talk, I mentioned: “You know, there are ways of automating and expanding what you’re doing,” and one thing led to another.

At the time, Damien was working at the Smithsonian; he’s now at Stockholm University. We’re in touch often, Twitter direct messages, mostly. We use basic online collaboration tools to keep on the same page. I tend to explore the more technological rabbit holes; Damien, as an osteologist, is working on provenance research on museum collections, which is a complementary project to our current one. But it helps us to understand just what we’re looking at as we collect these digital traces.

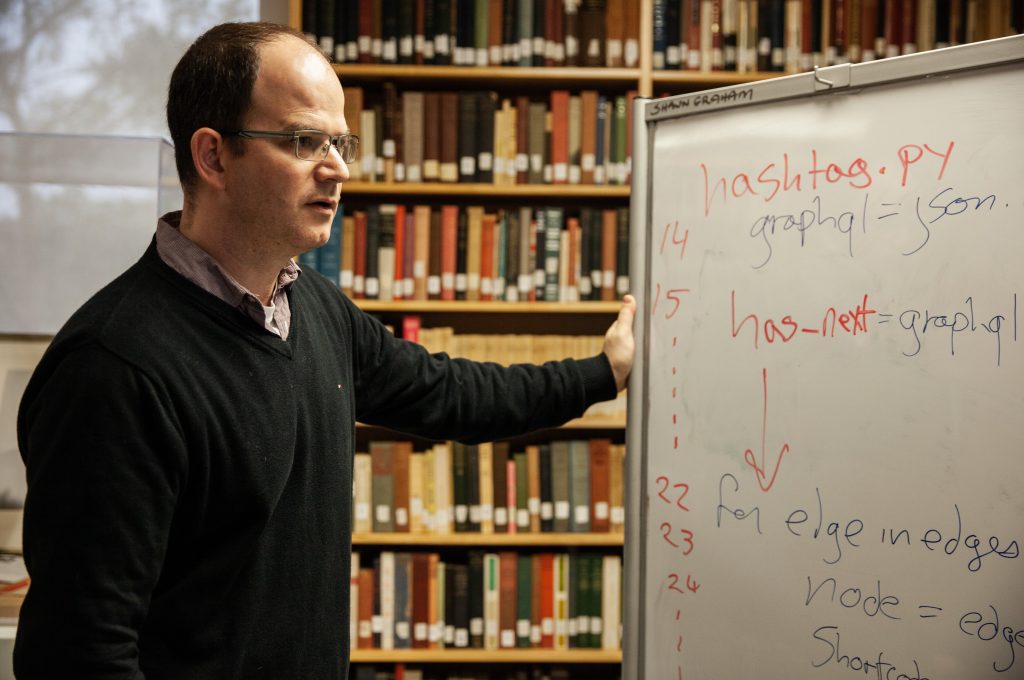

Photo Caption: Graham and Huffer in the midst of a brainstorming session.

What are some of your broad stroke social and technological objectives with this SSHRC funded project?

Technologically, we want to see just how far we can push this technology, what we can achieve with it, and where the dangers and pitfalls are — technologically, socially, and ethically. A lot of damage was done in the name of “science” when 19th and early 20th century scholars pulled these collections of human remains together — often without permission, often without the knowledge of, the peoples whose ancestors these were. A lot of energy was expended in trying to “prove” various theories about the “fitness” of various “races,” using these remains. A lot of the material circulating online now often claims to be from “a deaccessioned study collection” or a “medical collection.” If that’s true, then it comes loaded with all the same moral and ethical issues, and we have to do what we can to figure out where these remains come from. Even if it’s not true, we still need to find out where these remains come from — just this summer, 20 700-year-old skulls were stolen from a crypt in Kent.

Ideally, we’d like to return some of the humanity to those whose remains are being sold. Perhaps we will be able to reconnect the remains with the people, families, and cultures of which they came.

Tragic.

Yes. But can we actually do what we’ve set out to do? Computer vision companies promise to be able to determine race and ethnicity from photographs where key points are identified and compared against reference collections. This is to recreate the same sins of the social Darwinists, the race theorists. Identifying descendent communities for the people in these photos we discover — because you have to remember, human remains were people and still are if we could only connect them to their stories, their names — might not be possible; to even try might be to revisit the same kind of violence again.

And so, our goals are more modest. We want to understand what motivates people involved in this trade, how they go about organizing this trade, the extent and influence of the trade. The technology allows us to work out how images cluster across the tens of thousands of photos we’ve collected, and from those clusters, the patterns of intent. We want to show how the technology works, understand its limitations so that it can be applied usefully, purposely, and ethically across other historical disciplines.

Ideally, we’d like to return some of the humanity to those whose remains are being sold. Perhaps we will be able to reconnect the remains with the people, families, and cultures from which they came.

This part of the research is obviously very disquieting — how people market and desire to consume the dead.

Clearly, ethics and morality are front of mind as you do this work. What do you believe the continued interest in the trade of human remains says about contemporary Western ideals and what, in your opinion, are some of the oppressive properties of social media?

Beatrice Martini, a research fellow at Harvard, has a succinct definition of colonialism: “the practice of a power extending control over weaker beings or spaces.” This then can easily be understood in the digital realm as we see things like Facebook Zero, or the erasure of net neutrality, or Cambridge Analytica buying and selling our identities, or the arrangement of platforms such that the “ideal” user is a white man from southern California (Twitter). Digital colonialism is the arrangement of our technologies so as to extract value, make our surveilled presence online always a form of labour, and pull the fruits of that labour into the hands of the very few indeed.

So here we have a platform — Instagram — being used to facilitate the flow of (most often) non-white bodies as actual commodities. The highest prices are always commanded by materials that are presented as the “other”’, as “tribal”, non-white, non-Western.

Digital colonialism is the arrangement of our technologies so as to extract value, make our surveilled presence online always a form of labour, and pull the fruits of that labour into the hands of the very few indeed.

Thanks, Prof. Graham. I believe you’ve left our readers with a lot to think about. How can people and students connect with you if they’d like to further engage in this discussion on the red market and/or modern approaches to archaeology?

Don’t buy human remains. Replicas abound; use those. Follow our project website at bonetrade.github.io for updates, presentations, videos, and tutorials.

Professor Shawn Graham’s eCampusOntario funded textbook project, ODATE: the Open Digital Archaeology Textbook Environment has won the 2019 Archaeological Institute of Archaeology Award for Outstanding Work in Digital Archaeology.