Ottawa, Reconsidered

By Nick Ward

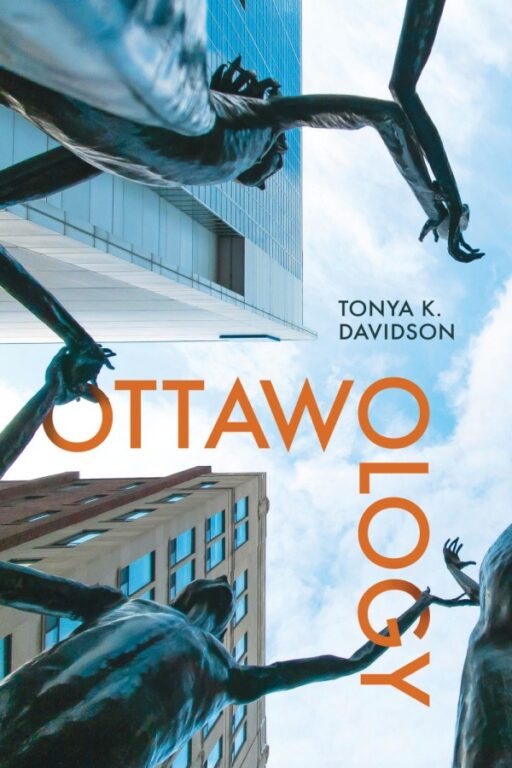

In Ottawology, Carleton sociologist Dr. Tonya Davidson reframes the capital through the everyday spaces where civic life actually unfolds

There is a familiar narrative about Ottawa as a sleepy government town defined by suburban public servants, national institutions, and a kind of demure political decorum. It’s a way of seeing the city that flattens it into symbols and stereotypes. But as Carleton sociologist Dr. Tonya Davidson explains, that framing misses far more than it captures.

In her book titled Ottawology, Davidson reframes the city by shifting attention away from sweeping tropes and toward the everyday places and systems where people actually live alongside one another. “This is also Ottawa,” she says, describing how she opens the book by holding two spaces together.

The first is the Rideau Chapel at the National Gallery of Canada, a heritage ceiling rescued in the 1970s and re-situated within a national institution. The space is carefully curated, and can feel formal but for Davidson, it is also deeply sociological. In the chapel, visitors can be “overwhelmed and moved by the collective sounds” of choral music, but also step close to hear individual voices, one by one. It becomes a way to think about what sociology does at its best: paying attention to the relationship between the individual and the collective.

She then moves a few kilometres away to Dundonald Park in Centretown, a dense and contested public space that reveals a very different register of city life. Here, people picnic, play music, organize protests, bring their kids, make art, drink, and spend long afternoons together. It is also a place where unhoused people use drugs, where police presence is constant, and where tensions around safety, care, and surveillance are impossible to ignore. These conditions are often framed through fear or avoidance, but Davidson reads them differently, as part of the social reality the city is continually negotiating. “Great things happen collectively at Dundonald Park which are moving in this very sort of everyday way,” she says. “The Ottawology of this book is both about sort of Ottawa as a national capital space, but it is even more about the Dundonald Park-ness of Ottawa.”

Ottawology is not a civic love letter that looks away, nor is it a detached inventory of urban problems. Instead, it offers a sociological map of a city shaped by power, memory, infrastructure, and ordinary social life, one that is attentive to who benefits, who bears risk, and whose needs are routinely underfunded or ignored. Davidson, whose research spans urban spaces, public memory, nostalgia, popular culture, and Canadian identity, has spent years thinking about how cities train us to see and what they subtly teach us to ignore. Ottawa, she argues, is an ideal case study precisely because it is so legible and so routinely misunderstood.

One of the book’s recurring themes is that what we often perceive as mundane is anything but. Libraries, malls, bus routes, parks, department stores, dive bars, community centres. These spaces are routinely overlooked precisely because they are familiar. Yet they are where belonging is practiced, where inequality becomes visible, and where civic life is either sustained or quietly eroded. Davidson draws on the idea of “third places,” popularized by Ray Oldenburg, to describe informal public gathering spaces with low barriers to access, places where people can spend time without being fully absorbed into the demands of home or work.

Ottawa, Davidson suggests, is a particularly revealing site for this kind of analysis precisely because of “how unexceptional it is.” Beyond its capital status, the city shares many of the same social pressures and vulnerabilities as other North American cities, including the fragility of public and quasi-public spaces. She traces older forms of third-place life through Ottawa’s early 20th-century department stores, where shopping spaces doubled as safe, socially acceptable places for women to linger, sit, and socialize. When these places disappear, she notes, people aren’t only losing stores. They are losing places to be.

The stakes, in Davidson’s view, are both personal and civic. “Suburbanization and automobility… encourage privatization of life,” she says, narrowing daily contact with difference and making isolation feel normal. Public transit, by contrast, can be one of the few places where a city routinely forces us into small acts of social negotiation, patience, and shared presence. Those micro-interactions matter more than we tend to admit.

The book also asks readers to sit with the less comfortable dimensions of city life, the places where power becomes visible in ordinary, often unnoticed ways. Drawing on Ottawa-based research, Davidson addresses policing, security, and the uneven distribution of surveillance and violence across the city. She notes plainly that “one of the biggest threats to the safety of sex workers in Ottawa is violence at the hands of the police.” These are not abstract concerns, but everyday realities shaped by policy, perception, and proximity. Including them, Davidson argues, is part of the book’s ethical work. Readers may arrive expecting a gentle tour of civic landmarks and find themselves instead thinking about whose safety is protected, whose is threatened, and how power quietly organizes daily life.

At the same time, Ottawology moves beyond human-made spaces and social relations to consider the broader systems that make city life possible in the first place. One of the book’s defining moves is to treat Ottawa as a city shaped by intersecting human and non-human lives, whose futures are inseparable from the natural environment. This, Davidson explains, is a way of seeing the city more fully, one that recognizes how land, water, light, and infrastructure are active participants in life and community and not just passive backdrops “It is a truthful understanding of Ottawa. Grounding the city’s growth in settler colonialism and environmental extraction. Ottawa only became the sort of white settler site of habitation because of the bounty of the forest here,” says Davidson.

From historic timber pollution to contemporary sprawl, the natural world is a part of the city’s social fabric, and it bears the consequences of urban decisions. “Suburban expansion is happening on wetlands that are being completely obliterated,” she adds, pointing to the long-term costs of land-use patterns built around private mobility.

Clearly, Ottawology is not built on a single new field project or perspective. It brings together decades of Davidson’s sociological research conducted in and about the city, much of it produced at Carleton. She points to the depth of work emerging from the university’s sociology community and the many graduate students and faculty members who have been studying Ottawa for years, often without naming the project as such. “They were being Ottawaologists without knowing it,” she says.

In fact, the book’s origin story is about teaching and learning at the university. During a 2020 sabbatical, when fieldwork wasn’t possible, Davidson returned to a course she has taught for years: the Sociology of Ottawa. She began transforming lectures into chapters, a process she describes as freeing precisely because lectures demand clarity, accessibility, and connection. “It’s written really in that style,” she says.

When she imagined readers, Davidson pictured two ends of the same civic spectrum: “my first-year students… and also the 93-year-old that’s spent 72 years in Ottawa.” She also wrote for the crucial people who quietly keep neighbourhood life functioning: community associations, local historians, public memory workers, and volunteers who maintain parks, protect trees, and organize small events that make a city livable. And she wrote for those who love Ottawa enough to want more from it.

Increasingly, she wrote with children in mind. “When you know a baby… you think about the future in an extended way,” Davidson says. In the book’s dedication, she names the children in her life who have helped her see the city differently, and whose futures will be shaped by decisions made now.

Ottawa will turn 300 one day, she notes, and those children may be there to see it. “Hopefully, there are still trees here and the animals still have their homes,” she says, “and there are places where people can listen to music on a Tuesday.”

That future-facing sensibility is what ultimately gives Ottawology its urgency. The book invites readers to slow down, look more carefully, and recognize the social life already unfolding around them. For anyone who thinks they know Ottawa well, or who suspects they might not, Davidson offers a compelling reason to take another look.