Studying Affect

How are you feeling today?

How have you felt over the past couple of years?

Feeling off ? Unfulfilled? Are you concerned about the ecological future of our planet? Perhaps you’re feeling confused or angered by the actions of others? Generally speaking, are you unsure of yourself and your place in society?

Professor Ann Cvetkovich, feminist and queer scholar and leading affect theory expert can help explain these feelings and why they are important.

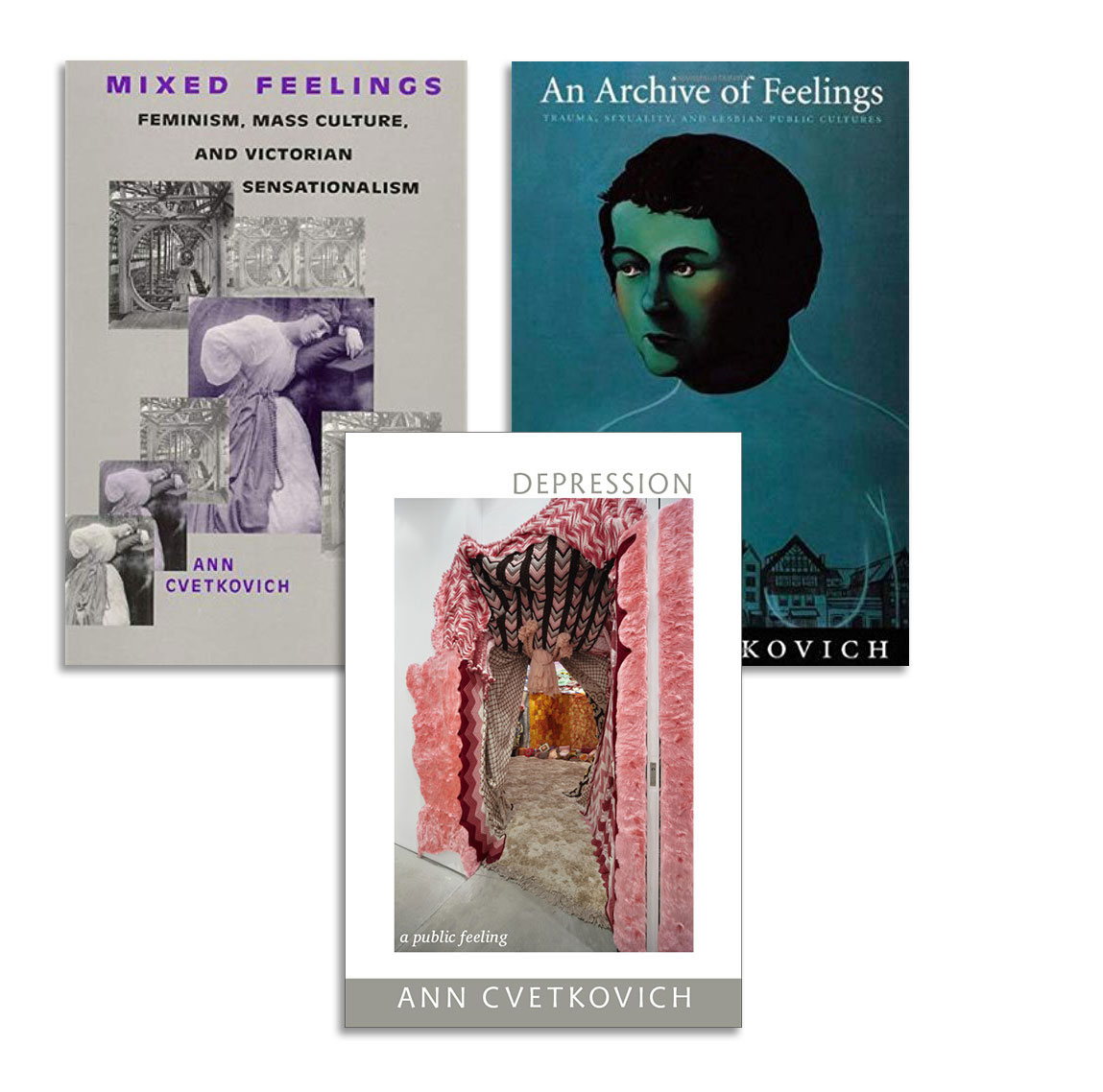

Cvetkovich, the author of the often-cited and interlinked books Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism (Rutgers, 1992); An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke, 2003); and Depression: A Public Feeling (Duke, 2012) has just arrived at Carleton as the new Director of The Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies. She comes from the University of Texas at Austin after a distinguished tenure as the Ellen Clayton Garwood Centennial Professor of English, Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies, and inaugural Director of LGBTQ Studies.

“Affect theory, or the critical study of feelings, enables the academic examination of emotional responses to real-world occurrences and structures that affect people,” explains Cvetkovich. Personal — or felt — experience is foundational to understanding how people traverse the world as both individuals and as publics. “Obviously, experiences differ from person to person.” says Cvetkovich. “White privilege is going to give you one experience of walking through space while being someone who is visibly genderqueer might get you another experience. So, what does that mean at the level of senses and how does that affect people’s realities?”

Along with others interested in political affect, Cvetkovich has frequently focused on the dialectics of hope and despair and particularly on negative feelings of unhappiness, depression, and failure, which often manifest themselves in irrational and desperate behaviours — actions which further nullify any hope of a resilient happiness. To decipher this phenomenon, Cvetkovich asks people to explore what it is exactly that they are chasing. “The idea of an attainable good life looms large,” says Cvetkovich.

Accompanying theorists of the “good life,” such as Lauren Berlant on “cruel optimism” and Sara Ahmed on “the promise of happiness,” Cvetkovich is interested in how fantasies of the good life promise one thing and deliver another. The dream of the good life offers the potential to emancipate people from the consternations of feeling unfulfilled and part of its seduction is that a better life always seems to be right around the bend — it’s just a matter of landing that job or starting that carbless diet. Feelings of fulfilment are believed attainable because the CEO, the celebrity, and social media influencers all seem to have them.

In reality, says Cvetkovich, for most, the mythical good life is unfeasible given that the predominant social structure is racist, homophobic, misogynistic, and panders to the already wealthy and powerful. “Affect and cultural studies explore how larger social systems are experienced at the level of sensation or embodied feeling,” says Cvetkovich. “How does capitalism feel? How does racism feel, and sexism feel? How does the political economy we’re living in feel?” she asks. “These structures have potent consequences on feelings. It also must be noted, that this violence can take many forms from assault to a subtle glance.”

These concepts are explored through Cvetkovich’s most recent book (released in 2012), titled Depression: A Public Feeling, which analyzes depression as a social and cultural phenomenon. The book also includes a memoir section in which Cvetkovich reflects on her own angst and despair and how these feelings have a affected her everyday experience, both personally and professionally. In Depression: A Public Feeling, she considers how her own coping strategies — ordinary activities from swimming and yoga, to visits to the dentist — which have helped to boost and soothe her.

Reflections and Meditations From a Life Focused On the Influence of Feelings

Born in Vancouver and raised on Vancouver Island, Cvetkovich moved to Toronto when she was ten years old. Regionally, Vancouver and Toronto are very different places, and she was shaped by both of them. The beautiful, humbling B.C. oceans and terrain remain today as foundational inflfluences for Cvetkovich, but it was the urban crucible of Toronto in the sixties and seventies that ignited her interest in examining people and culture.

“At the time that I lived in Toronto, the city was in a state of transition, and new waves of immigration transformed it.”

Cvetkovich attended Harbord Collegiate Institute in downtown Toronto, a school whose students were the children of immigrants from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Portugal, Bangladesh, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, Italy, and elsewhere. Her family lived in an evolving neighbourhood that included many new faculty members at the University of Toronto who had come to Canada from the U.S. “Also, very important to the fabric of Toronto in the sixties were the Vietnam War draft dodgers who had immigrated to the city and brought with them anti-war activism and a belief in the power of community, activism, and art,” says Cvetkovich.

This hippie counterculture and alternative student advocacy was a potent mix for a precocious young person. “I had the benefit of a very radical and cosmopolitan culture in a distinct era and place.” Her experience in Toronto also inspired curiosity about life outside Canada’s borders. And so, Cvetkovich moved to the U.S. to study Literature and Philosophy at Reed College, a small liberal arts school in Portland, Oregon and would continue on in grad school at Cornell in Ithaca, New York where she would complete both her M.A. and PhD in English at a time when critical theory was on the rise.

Through her transition from undergrad to graduate school, Cvetkovich started conceptually wrestling with the Cartesian split between mind and body, or reason and emotion, which took her beyond the parameters of a single academic discipline. Just as pressingly, she sought to discover what arts, culture, and creativity can contribute to causes of social justice around the world. The interdisciplinary school of feminist thought was just beginning to make an impact. “Feminist forms of critique opened everything up for me, and I began thinking critically about existing systems of knowledge and the possibilities of creating new knowledge through the exploration of felt experience.”

At the time, what is referred to today as affect theory did not exist. Instead, there was a small and marginalized field called the philosophy of emotion, which piqued her interest.

Cvetkovich was intent on unpacking and exposing the omnipresent sexist dichotomy between reason (classically gendered as masculine) and emotion (problematically gendered as feminine). In doing so, Cvetkovich was set on demonstrating just how massively influential feelings are on all aspects of life as we know it.

Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism

Her first book, which doubled as her PhD dissertation, Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism (1992), helped create the field of feminist affect studies through its focus on popular genres for women that sought to create strong feelings. For Mixed Feelings, Cvetkovich uses the tools of feminist, Marxist, and poststructuralist theory to examine how depictions of trangressive women, in Victorian sensation Novels provide a mechanism for readers to express dissent and rebellion. The book also includes a chapter which examines Marx’s Capital as a Victorian sensation novel. Here, the focus is on how Marx depicts capitalism as a Gothic monster and documents its effects on workers using melodramatic and sensational representation.

“My argument in Mixed Feelings emerged from the good-old feminist touchstone that the personal is political. How we feel matters to understanding social structures,” explains Cvetkovich.

After wrapping up her PhD, Cvetkovich landed a position as professor of English and of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, where she would remain until 2019.

An Archive of Feelings

For her second book, An Archive of Feelings (1993), Cvetkovich draws from a sex-positive feminism and AIDS activism to develop a queer approach to trauma that addresses sexual and affective experience, including everyday forms of injury. Critiquing medical models of PTSD, Cvetkovich seeks to expand the category of trauma to include not just the Vietnam war veterans whose experiences were the foundation for the diagnosis. Her project was also inspired by new archives of trauma testimony that sought to record the experiences of Holocaust survivors, and she was interested in expanding the frame of historical trauma to include slavery, the colonization of Indigenous peoples, and migration and diaspora. Starting from a focus on lesbian survivors of sexual violence and lesbian AIDS activists, Cvetkovich found herself shifting from trauma to ordinary experiences of loss and mourning. To do so, she also had to develop new tools for documenting ordinary affective experience and thus found herself wondering how to create an “archive of feelings.” The book closes with a discussion of an actual archive, the Lesbian Herstory Archive, and her research there led her to her next project, an exploration of how LGBTQ archives are providing new counterarchives and critical understandings of public history, including trauma histories.

An Archive of Feelings continues to inform Cvetkovich’s interest in testimony, oral history, memoir, storytelling, and other genres of public feeling that use personal narrative as a form of historical and social knowledge. “Listening to people and offering them witness helps show them that their struggle — the injustice and violence that they have faced — is essential and will be remembered. This is often transformative,” she remarks.

Coming to The Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies

In her return to Canada by taking a position at Carleton University, Cvetkovich brings with her a career of encouraging a deeper understanding of the complexity of violence, from physical harm to micro-aggressions felt every day by the marginalized. Moving forward she continues to seek new ways to document and convey the gravity and nuance of lived experience. She is currently focused on methodological and scholarly experiments in format — from oral history archives and personal narrative, to video documentaries and art practices. “I’ve long been inspired by the theatre of protest, and cultural activisms, like drag performance, for example, that implement humour and flamboyance to deliver cultural messages.”

“I’m also inspired by Indigenous scholars such as Dylan Robinson who explore arts and culture as a different pathway to resurgence and as a critique of conventional models of reparation. I hope to learn more here in Canada,” says Cvetkovich.

For Cvetkovich, the dynamism of the Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies (PJIWGS) was one of the draws to joining the unit here at Carleton. “I’m really interested in institutional change and interdisciplinary spaces, so this job is an opportunity to share my values in collective action. I’ve joined forces with very impressive colleagues who are also keen to discuss new configurations of feminist studies for the 21st century that reflect its intersectional, transnational, and decolonial ambitions.”

“I’m delighted with the integration of Disability Studies and Sexuality Studies into our unit. We’re having conversations on programming and pedagogy that consider our intersections and envision a critical diversity studies.”

While Cvetkovich leads the way for the PJIWGS she is also seeking to partner with other departments within the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (and beyond) to tackle issues of diversity and inclusion, and she is especially eager to coordinate with Carleton’s Indigenous Strategic Initiatives planning. “Universities are an important place to create new structures if we’re looking to decolonize, to change society, and and to fundamentally transform Canada,” she says.

Cvetkovich’s research on affect and feeling is undoubtedly complex, but complex thought is required to decode a complex world. The foundational message she imparts to her audiences is that your feelings are political, and if we can understand them, we can better grasp political consequences. Reckoning with feelings as a vital force in shaping our public and political spheres can be a step towards more radical and open democracies around the world. Just as critically important is understanding how feelings function adversely — how biased structures and institutions make us feel and cause us to feverishly hunt for the unreachable good life. Cvetkovich’s expertise in affect, gender and sexuality studies, and arts and culture are most welcome in FASS. “There’s so much excellence and potential at Carleton. I’m thrilled to be a part of it,” she says.

So … now that you’re familiar with Cvetkovich and her research and therefore appreciate that your response is dense with political and cultural meaning, ask yourself one more time: How are you feeling today?