by Marie Tremblay, CFICE Volunteer

The end of March will see this year’s 30 Hour Famine event by World Vision Canada, an event during which youth across Canada pledge to starve themselves for 30 hours to raise awareness and understanding of famine globally. Although World Vision Canada’s 30 Hour Famine aims to raise awareness about famine globally, it does target a problem that many families and individuals in Canada experience—food insecurity.

Food insecurity affects certain populations in Canada more than others. The main factor that increases the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity is household income, which in turn tends to disproportionately affect single parent families, immigrants, and First Nation families. These socioeconomic factors become increasingly important when paired with geographic location. This is why the most affected region is Northern Canada and why Indigenous people are more likely to be affected. According to a 2012 article from Statistics Canada, Nunavut had the highest percentage of food insecure households (36.7%) with the Northwest Territories (13.7%) and Yukon (12.4%) as second and third highest. The national average, in comparison, is 8.3%.

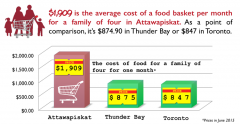

These trends are also supported by other sources and organizations that look at food insecurity in Canada. In fact, a report by Food Secure Canada (FSC) shows that the average cost of food for a family of four in Toronto and Thunder Bay is approximately $900. In contrast, Attawapiskat, a First Nation in Ontario, averages at $2,000 a month for a family of the same size.

Food Secure Canada “is a pan-Canadian alliance…[with] three interlocking goals: zero hunger, healthy and safe food, and sustainable food systems” in Canada. Amanda Wilson, a postdoctoral fellow working with FSC, describes their mandate as mainly advocating for policy changes that would allow them to “build the capacity of the food movement to engage in policy advocacy with the goal of a more just and healthy food system.” “Whether or not one is food secure impacts one’s health,” states Wilson, “[and correlates] with chronic disease and food security and also poverty—all these different ways where questions of food security, or lack thereof, have a ripple effect.”

Food Secure Canada “is a pan-Canadian alliance…[with] three interlocking goals: zero hunger, healthy and safe food, and sustainable food systems” in Canada. Amanda Wilson, a postdoctoral fellow working with FSC, describes their mandate as mainly advocating for policy changes that would allow them to “build the capacity of the food movement to engage in policy advocacy with the goal of a more just and healthy food system.” “Whether or not one is food secure impacts one’s health,” states Wilson, “[and correlates] with chronic disease and food security and also poverty—all these different ways where questions of food security, or lack thereof, have a ripple effect.”

FSC focuses on food insecurity in the North through Nutrition North, a federal policy that aims to alleviate some of the costs related to food in Northern Canada. A main part of this would be to support communities in gaining what Wilson characterizes as “culturally appropriate foods.” The FSC representative adds that this is important as current support to Northern communities is falling short. In fact, Wilson states, “I think that there’s pretty well a consensus that the program as its currently being implemented is not working…Food is not being subsidized effectively in the North.”

To advocate for changes in food policy, FSC works in partnership with other organizations. For instance the 2016 report released by FSC entitled Paying For Nutrition: A Report on Food Costing in the North was a collaborative work with partner organizations and scholars. These partnerships highlight how partnering with academic researchers and projects carries many benefits, especially in regards to funding. “We just wouldn’t have the capacity to do that on our own, so that report was a great example of community/academic collaboration,” Wilson states.

Infographic from the Paying for Nutrition Report.

FSC operates on what Wilson refers to as a “shoestring budget,” meaning that its funds can create limits in how FSC operates. “We are a small organization compared to other national organizations,” Wilson notes.

Academic researchers, for FSC, become important actors in terms of doing the research and supporting FSC’s efforts to change Canadian policies and promote the importance of food security. Wilson credits academics as doing a lot “of the legwork—going to communities, doing the food costing, generating the data, talking about the analysis—so it was a real project and process of community/academic collaboration which was so important for Food Secure Canada.” This exemplifies how crucial community work and research by academics can be for smaller organizations. According to Wilson, as “a small but mighty organization, these relationships can be really important to enhance our capacity and make the case, [and] provide the evidence base that allows us to make really strong arguments.”

In regards to CFICE, Wilson noted that “the CFICE project is all about thinking through how do we engage in those types of relationships in the ways that are more effective, more valuable to community partners, so I think that taking the time to think through those partnerships is really important.”

FSC tackles an important issue in Canada, and further academic research on food security and food policy should look at and contribute to FSC’s work. For more information on Food Secure Canada and their mandate, please visit https://foodsecurecanada.org/.