by Barbara Szijarto, member of CFICE’s Evaluation and Analysis Working Group

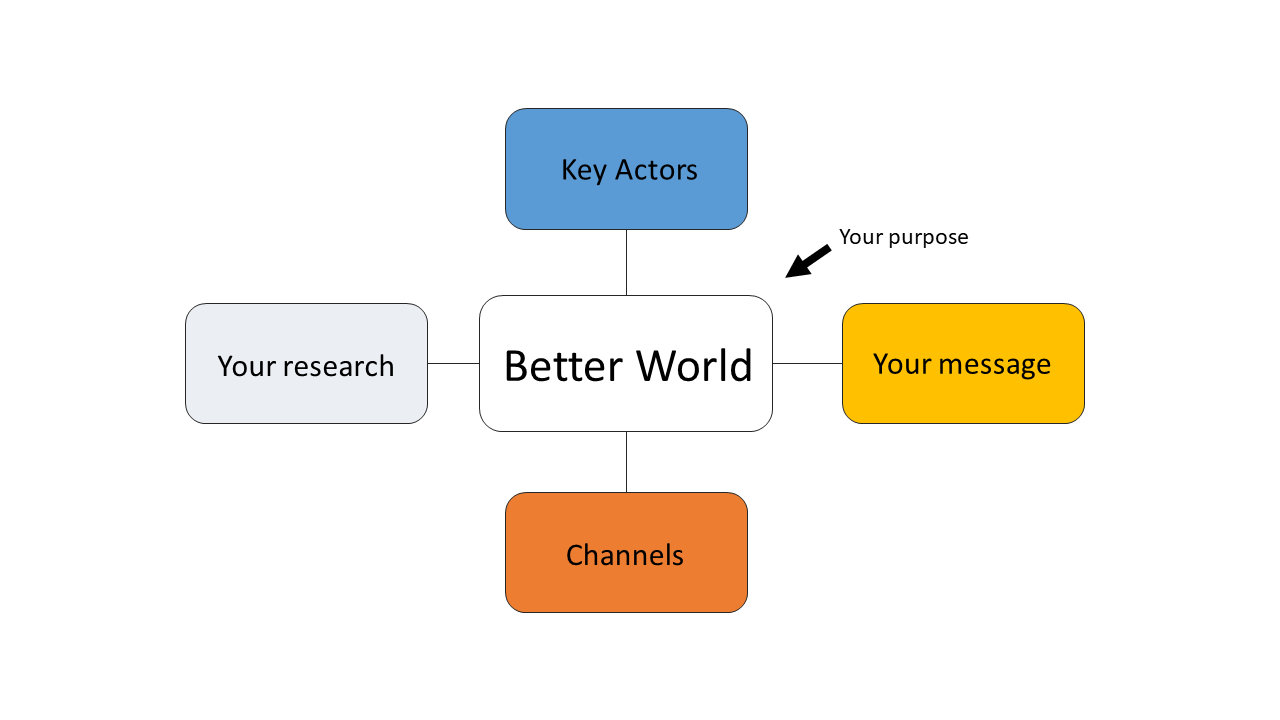

As researchers, we overcome countless hurdles to answer important questions. We care – passionately – about our methods, our data and our findings. We do it because we want to contribute to a better world.

We don’t do it just to talk with other academics.

Your work is not irrelevant. But your efforts to communicate beyond your own discipline might be. Face it, as academics we’re trained to master the art of talking to ourselves, with our own language, our own journals, at our own conferences.

How can we contribute to that better world if we stay inside our box?

Don’t lose hope. Your reach into the real world can be smart, thoughtful and way more effective, even without heaps of time and money.

So here’s how to get started on your world-changing journey.

1. Know your purpose

Sounds simple, but sometimes we get busy planning infographics and webinars without really thinking this out. What problem do you want to help solve? What would change if you were successful?

2. Map out the problem environment and know who’s in it

2. Map out the problem environment and know who’s in it

Who else is working on this problem? (Yes, that’s right, outside of academia). Talk to them. Educate yourself.

Learn about:

- Who makes decisions in the problem area. How? When?

- Who (or what) influences these decisions.

You could do some full-on systems mapping here. There are plenty of outstanding step-by-step resources to help, like this one from FSG.

If you’re not quite ready for that, here’s a simple little worksheet:

| Decisions | |

| Are made by: | (be as specific as you can, instead of ‘policymakers’ think about which departments, agencies and positions actually make decisions at the level you care about)

|

| Are influenced by: | (e.g., opinion leaders, advocates, specific policies or procedures, resources, geography) |

| Affect: | (e.g., families, marginalized youth, people on waiting lists)

|

You can find other worksheets and more advice in this great KT planning guide from the Institute for Work & Health.

3. Ask yourself: how is your research relevant to their decisions?

Are you sharing facts and/or data points (like prevalence data)? Do you want to draw attention to an emerging problem or counter a myth?

Do you have actionable information? Something that can be applied directly to a decision?

Or do you have more complex insights from your research? Not directive but important to how people frame the problem or possible solutions?

4. What does each actor need to use your research?

Think about what kind of change you’re asking them to make. Asking someone to pay attention to something, or to lend their support to an issue they already care about is different from asking them to alter their assumptions or beliefs. It’s a whole other ballgame from asking to people to change the way they do things.

Ask yourself: how big a change is this for them? Are there major barriers for them to overcome? How can you help them over these barriers?

| Actor | Type of change | Barriers to change | Supports |

| e.g. Academics invested in community-campus engagement | e.g. behaviour change (prioritize more community-focused outputs) | e.g. external barriers -tenure and promotion committees value academic publications over grey literature | e.g. teach methods for redeveloping academic outputs for community audiences |

Some frameworks, such as one from Lang, Wyer & Haynes (2007) group barriers into categories, such as lack of awareness, lack of agreement and external barriers (lack of time, legal risks, policies in the organization).

Check out this seminal article by Greenhalgh et al. (2004) for a primer on what helps and what gets in the way of the use of research in practice.

Try journey mapping. Journey mapping can help you step into the shoes of each actor and trace how, when and where key decisions are made, and what influences these decisions. Here’s a how-to post on journey mapping from Stephanie Evergreen’s blog.

- Is the change high cost or high risk for this actor? Can you guide them to a lower-risk/lower-cost way to try it out?

- Does the change require specialized skills or resources? Can you point them to where these can be found?

- Who might be advantaged or disadvantaged by the change? Consider interests at play. Give people context they need to avoid potential harm.

- What do actors see as credible information? People don’t act on information they don’t trust. Do you need to provide numbers? Rich description of lived experience? Local data (such as from their own region, or from a rural perspective)?

If you remember one thing, remember this: information is not knowledge. More specifically, your information is not their knowledge. If you’re not sure about the difference, check out this article by Contandriopoulos and colleagues (2010) and this response by Greenhalgh (2011).

Now, and only now, start thinking about formats, modes and channels to engage with actors

Way too often we jump to this first. We want infographics before we even know who we want to talk to. Don’t do this. Please. This is a quick path to being ignored.

As a researcher, would you choose a method for data collection without knowing what you want to collect, why, and from where?

Think about how you will reach the actors you need to reach, for this purpose, with this kind of information, considering their constraints, barriers and opportunities.

There’s an abundance of possibilities. Be smart. You can connect with communities of practice or opinion leaders, hold small-group workshops that encourage dialogue and exchange on more complex ideas. You can create digital storyboards (online, for free, here’s just one option), host a webinar, write a trade journal article…the options are endless!

Ok, that might seem overwhelming. Take a look at Melanie Barwick’s (2008, 2013) toolkits for knowledge translation planning. You’ll find a list of possibilities ranked by what research suggests is effective. Rules of thumb: multiple modes are likely to be more effective than a single mode. Distributing materials to actors hoping they’ll read them (passively, without interaction) is considered ineffective on its own.

But – in the end, it’s about the people you want to speak with. How will you help them change the world?

Resources:

Barwick, M. (2008, 2013). Knowledge Translation Planning Template. Ontario: The Hospital for Sick Children. Available at: http://www.melaniebarwick.com/KTTemplate_dl.php

Contandriopoulos, D., Lemire, M., Denis, J. L., & Tremblay, É. (2010). Knowledge exchange processes in organizations and policy arenas: a narrative systematic review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 444-483.

Gopal, S. & Clark, T. (n.d.). Guide to actor mapping. FSG. Available at: https://www.fsg.org/tools-and-resources/guide-actor-mapping

Greenhalgh, T. (2010). What is this knowledge that we seek to “exchange”? The Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 492-499.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., & Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581-629.

Lang, E., Wyer, P., & Haynes, R. (2007). Knowledge translation: closing the evidence-to-practice gap. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 49(3), 355-363.

Lyons, J. (2018). Journey maps. Evergreen Data. Available at: https://stephanieevergreen.com/journey-maps/

Reardon, R., Lavis, J. & Gibson, J. (2006). From research to practice: a knowledge transfer planning guide. Institute for Work & Health. Available at: https://www.iwh.on.ca/tools-and-guides/from-research-to-practice-kte-planning-guide